by Tiffany | May 23, 2017 | Health, Identity, Intersectionality, Patreon rewards, Personal

(Image is from gratisography.)

This is (sort of) a Patreon reward post. At $5 support per month, you, too, can have a personalized post on the topic of your choice during your birthday month! Because this topic ended up generating so much meaningful discussion about ageing, rather than trying to cram everything into a single post I have expanded it into a three-part series. All substantial blog posts are released to Patreon patrons one week early.

This is Part Two of the three part series. In Part One, we talked about the fear of ageing, and how to care for ourselves through those fears. Part Two is about the joys of ageing. Part Three, on the topic of fear of death and end-of-life preparation, will be next.

I struggled with writing this second post in the series. So often, an acknowledgement that joy is possible becomes weaponized – rather than gesturing towards a possibility, joy becomes an obligation.

Because so much of our culture, particularly in the self-help and self-care communities, focuses so hard on “manifesting” positive outcomes through positive attitudes, with the corollary victim-blaming coming along for the ride, I find myself hesitating even to talk about joy for fear of how it will be interpreted and how it could be turned as a weapon against the vulnerable, the hurting, the fearful among us.

The vulnerable, the hurting, the fearful – these are my people. Although I am a playful, sparkly, joyful person, I identify strongly with the parts of me that are almost always fearful, almost always hurting. My joy is a sparkle in the dark, rather than the other way around.

And so, part of my resistance to this second post was also my own cognitive distortions – my tendency towards all-or-nothing thinking (if joy is possible, then joy is always right and fear is always wrong!); my internalized victim-blaming (if I could just be happy, then I would be happy!); my fear of joy. Brené Brown writes, “I think the most terrifying human experience is joy. It’s as if we believe that by truly feeling happiness, we’re setting ourselves up for a sucker punch. The problem is, worrying about things that haven’t happened doesn’t protect us from pain.”

Although Brené Brown’s description of fearful joy is not universal, it certainly does ring true for me, and is part of why I often hesitate to embrace joy in my own life. Letting go of the fear feels as if it will open me up to tragedy. If I am constantly afraid, maybe I won’t end up hurt?

But is it not possible to fully engage with the range of responses I got from people without engaging with the joy that some of them expressed. The anticipation. The freedom that they saw in ageing, and the carefree delight of it. An honest engagement with my research means pushing through my anxiety and digging into this rich and uncomfortable soil – the terrifying possibility that joy is lurking.

What I learned from the generous responses of the people I spoke with is that ageing isn’t all bad, and our relationship with ageing doesn’t have to be one of fear and dread. This is true despite the fact that many fears that people expressed are completely valid and grounded in the reality of ageism (and the many other intersections of marginalization that exacerbate the impact of ageism), as well as real economic and social threats. Some people are able to see the positive sides of ageing, regardless of the scary things.

This joyfulness is not solely the realm of the privileged. There are people facing sexism, racism, cissexism, binarism, ableism, sizeism, and many other marginalizations who still find joy in the idea of ageing, and there are many people with various privileges who view ageing with significant fear. It’s important to acknowledge that each person responds to situations in their own individual ways, informed by their culture and family of origin, their available resources (including social, emotional, mental, and material resources), and with their own unique outlook. There is no “right” or “wrong” way to approach ageing – the fear is valid, and so is the joy.

And, importantly, the fear and joy often coexist.

Emily, who also talked about fearing increased pain and loss of mobility, says, “I call grey hairs wisdom strips and love getting older and feeling more content to be myself. The growing invisibility works well with my personality too.”

Although Tammy expressed anxiety about losing physical and mental abilities and being on the receiving end of our culture’s abysmal elder care (such a common, and reasonable, fear), she also said, “On the positive side, I menopaused at 47 and am quite happy with it. I also love being able to do whatever I want as my kid is now an adult, I have no partner, and I don’t give a flying f*** what anyone thinks.”

Similarly, Nicole talked about fearing loss of mobility, but started by saying, “I quite enjoy getting older now, as I feel like I’m at the stage where I’m becoming the person I want to be, someone I (mostly) like.”

That sense of confidence and self-assurance was a theme in a lot of the joyful responses, and it makes sense. One of the benefits of ageing can be a more solid sense of self, and less concern with what other people think about you.

Nadine’s comment exemplifies this. She says, “I enjoy getting older a lot. Possibly because I don’t associate my childhood and teen years with the kind of vitality most people ascribe to “youth”. I wasn’t a particularly strong, healthy, nimble or attractive to my peers as a child or during my teens. I didn’t have much control over my circumstances. I had strong instincts but lacked the maturity, intellectual skills and verbal ability to articulate or even fully understand what those feelings were about.

The more time passes, the more I understand my mind and my body. I know a lot more about how to take care of myself and my health. I’ve accepted what I look like. I can express my inner thoughts and emotions. I have some agency in my life. I don’t love how crunchy my knees are, but apart from that, getting older is my jam!” (Nadine is a fantastic sex educator, and specializes in supporting sex positive families – coaching parents and providing resources for kids.)

Margaret also expressed joy at feeling more confident. She says, “I’m turning 44 this year. Not afraid of aging. Kind of enjoying being treated less like a sexual object and more like a social subject. Increasingly feeling competent and confident. Slightly afraid symptoms associated with aging (physical problems, etc.). A little vain about how I look as I age, but finding a style that works for me.” (Margaret is an academic activist, and when I was but a wee little researcher and had recently come out, finding her Introduction to Bisexual Theory syllabus online changed the trajectory of my academic career, and started the journey that led to my community activism.)

Andrea says, “I know I’m still quite young, but aging is something that I’ve really enjoyed. Physically and mentally, I’ve never felt a desire to go back and even tho the future is daunting sometimes it’s something I constantly crave. Physically (this is what I hear emphasized a lot from people in my life) I’m not in a hurry for things like grey hair and wrinkles but my impression of them is that when they do come I will have earned them. I think they’re cute and, like, stretch marks or scars, they’re a sign that your body has existed in time and space, and has been literally shaped by experiences.”

I really love the idea that the inevitable signs of ageing can be “sign[s] that your body has existed in time and space, and has been literally shaped by experiences” fits to beautifully with my own narrative approach to self-understanding. Grey hair (which I’ve had since my teens) and wrinkles don’t bother me, but other changes in my body, particularly related to the fibromyalgia, have really bothered me. I sat with the idea of these changes being signs of my body being marked by my time here, and although I’m still pondering it, I do think there’s something valuable in the idea.

I’m conscious of the impact of trauma on the body, and how adverse childhood experiences and histories of abuse can impact our bodies. It’s one of the things I work on in my writing workshops and coaching sessions, and it’s something I’m very interested in in my own life. Although I’m not sure where this little thread of thought will end up, I wonder if there some valuable restorying that can happen if we take our bodies’ responses to trauma and see them as signs of existence and experience.

Another factor in finding joyfulness in ageing has to do with our exposure to old people and to the process of ageing. Being around old people is one way to reduce our fears of ageing, and to recognize that life does continue past the wrinkles and walkers. (Again, this is not always true. A traumatic experience with witnessing ageing might have the opposite effect.)

Another Margaret says, “Growing up I was very close to my grandfather who is vibrant and alert and still working up until very sudden death the age of 86. My grandmother died she was 92. Ageing never seemed scary to me as they set an example of independence, connections with family friends and community, constant learning and enjoyment of life.”

A 2013 study into the perceptions of successful ageing among immigrant women from Black Africa in Montreal found that the old women identified four elements that they considered essential for successful ageing. These were social engagement, intergenerational relationships, financial autonomy, and faith.

Social engagement, intergenerational relationships, and financial autonomy are all linked to both the fears identified in Part One, and the joys identified here.

The 2014 paper, “Strategies for Successful Aging: A Research Update,” found that physical activity, cognitive stimulation, diet/nutrition, complementary and alternative medicine, social engagement, and ‘positive psychological traits’ were all correlated with a higher likelihood of ‘successful ageing’ (though this term itself is contested and complicated).

These ‘positive psychological traits’ include a wide range of qualities such as resilience, adaptability, and optimism, and the reason the range is so wide is because they are most often self-identified among people who consider themselves to be ‘successfully ageing.’

(Again, that flutter of anxiety that identifying these potential helpful traits will be turned into obligations and used to blame people for their own struggles. I think this fear is a side effect of doing so much reading in the self-help section as research for my work as a coach, and being bombarded so often with weaponized positivity!)

But rather than taking a prescriptive view of these helpful traits, I think that we can take a narrative approach and part of our self-care around ageing can include looking for the stories in our own histories that demonstrate resilience, adaptability, and optimism – the times when we bounced back, when we adapted to a new situation, when we kept our heads up despite the weight of discouragement and the times when we didn’t but we also didn’t stay down.

This feels important, because it gives the stories we tell about ourselves and about our psychological traits power and meaning, and we can change the stories that we tell even when we can’t change the situations around us. This does not mean that we can remove ourselves from the toxic soup of racism, sexism, ableism, ageism, cissexism, etc. with the power of our minds. But it may mean that we can mitigate some of the damage, and give the systems that want to destroy us a gleeful middle finger. (While also recognizing that financial security as a determinant of successful ageing is one of the cruelest things imaginable in our current context of late capitalism.)

So, what does that mean for our self-care practices?

I think that these stories of joy and anticipation can be an invitation to look for opportunities to view ageing differently. Our self-care can include intentionally looking for ways to engage with joyful approaches to ageing.

We can also start to examine our views of ageing, and look for the stories that we’ve internalized about the ageing process and about what it means to be older. Our fears are valid, but there is also joy possible.

We can try to incorporate more intentional social engagement, particularly across generational gaps, into our lives.

We can keep our brains active by allowing ourselves to be curious and enthusiastic about our interests.

And, I think, we can work at accepting our ageing bodies – seeing the beauty in these signs that our bodies have existed in time and space, and been shaped by our experiences.

Further reading:

Alyson Cole’s article, “All of Us Are Vulnerable, But Some Are More Vulnerable than Others: The Political Ambiguity of Vulnerability Studies, an Ambivalent Critique.” This paper is behind a (significant) paywall. If you have access to it through a library, it’s a worthwhile critique of vulnerability studies, and since I cite Brown in this post, it’s important to acknowledge and examine the ways in which her framework fails to do justice to complex issues.

On a similar theme, Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg’s essay, “Shame and Disconnection: The Missing Voices of Oppression in Brene Brown’s ‘The Power of Vulnerability’,” which is available freely on The Body is Not An Apology.

Nick Yee and Jeremy Bailenson’s article, “Walk A Mile in Digital Shoes: The Impact of Embodied Perspective Taking on the Reduction of Negative Stereotyping in Immersive Virtual Environments.” This is such an interesting study, with very cool implications for challenging our own negative stereotypes about a range of people, including elderly people. I would highly recommend reading this one.

Jeanne Holmes’ 2006 dissertation, “Successful Ageing: A Critical Analysis.” I haven’t read this whole dissertation, but I found parts of it very helpful in understanding the differences between how we conceive of successful ageing and how older people themselves experience it.

by Tiffany | May 16, 2017 | Health, Identity, Intersectionality, Narrative shift, Patreon rewards

(Picture of Jonathan and Tiffany on Jon’s birthday.)

This is a Patreon reward post. At $5 support per month, you, too, can have a personalized post on the topic of your choice during your birthday month! Patreon posts are available to patrons one week early. (This post is late, because there were a few emergencies and illnesses in my life, and I appreciate Jon’s patience with me!)

Jonathan Griffith is one of my best friends, and has been one of my romantic partners for the last eight and a half years. Over the course of our relationship we have come out and explored bisexuality together, learned how to do polyamory together (cut our teeth on each other, and have the scars to prove it). Jon was also there when I came out as genderqueer, and together we navigated that tricky terrain of shifting identities. We also lived together for a few years, managed the phenomenal feat of transitioning out of living together while remaining partners, and I am confident that we will be in each other’s lives as loving partners for as long as we’re both kicking around in these corporeal forms. Which, I hope, will be quite a while longer.

And that brings me to Jon’s requested topic: self-care, narrative, and fear of ageing.

Similar to the emotional reaction I had to Red’s post request about self-care and navigating post-secondary and professional environments while struggling with chronic illness and mental health issues, Jon’s request touched on some of my own exposed nerves.

I consider myself fairly at peace with ageing – I am almost entirely grey at 35, and am okay with that. I like my wrinkles. My teen years were a bit of a trainwreck and I didn’t even have an orgasm until after my divorce. I often consider my life to have (re)started at 27. So, when I first approached this topic, I anticipated it being an easy write. Find some good posts to link, write about how to self-care ourselves through our fear, pat self on back, done.

But ageing is more than just grey hair and wrinkles and birthdays. The fears around ageing are more than simply superficial. Scratch at the surface of these fears, and some of the ugly aspects of our cultural fixations on youth-and-beauty, work, and individualism come quickly to the surface. Economic and social anxieties bubble within these fears, and as a result many people have a complex and fraught relationship with ageing (or with the changes ageing might bring). There are material fears – loss of mobility, beauty, the ability to work or move or think; there are social fears – loss of social standing, loss of community; there are existential fears – death. There are also joys associated with ageing. It’s complex.

I asked about people’s feelings about ageing on my facebook, and the responses flooded in. There were so many, and they touched on so many critical issues and divergent experiences, that I’ve decided to turn this post into a three-part series.

The first part of this series is directly related to Jon’s original request – the material and social fears of ageing. We’ll look at what people are afraid of, and introduce some self-care tips for navigating those fears.

The second part of the series will address the joys of ageing.

And the final part of the series will address fear of death, and end-of-life preparation.

So, let’s dive into this complex topic!

We’ll start with one of the most commonly discussed fears of ageing – fearing the loss of attractiveness and desirability. This fear seems to disproportionately impact folks who are not allowed to look old or to lose their conventionally attractive physical features – where straight men may be given more leeway to age visibly, queer men and women, as well as non-binary individuals, are given much less flexibility to age in public. (This is not to imply that straight men don’t face unrealistic body expectations, only that there are cultural templates available for men to age visibly, that do not exist with the same frequency and diversity for queer men or people of other genders. Race and class also impact the willingness of society to grant a person the right to age visibly.)

Speaking specifically about this fear, Collin said, “I find as a queer cis-man that, although I try to resist it, so much of my value comes from being seen as attractive and so many of the messages within cis-male queer circles focus on older men being less attractive and therefore worth less so despite all my efforts to reject those notions, I still encounter the constant micro aggressions aimed at men of my age and older and I find myself succumbing to those feelings of questioning my worth as I age.”

Lyn echoed Collin’s fears: “I never used to be afraid of aging.. Now I’m very afraid. I’m approaching 40 and it makes me sick to my stomach. I find I’m stuck in the bullshit narrative that women have an expiry date. I’m no longer young and pretty. I’m not fit or slender… I have grey hair and I’m starting to see wrinkles and my skin is losing elasticity and a hundred million other details I can see every day in the mirror. I feel more and more obsolete.”

These fears may seem superficial, but there are real concerns underlying them.

Both Lyn and Collin’s concerns about desirability are echoed in Saryn’s fear. She said, “I’m afraid of losing respect and opportunities.” And it is all too true that women often do lose respect and opportunities as they’re seen to age. The expectation of youth and beauty extends beyond romantic relationships and is present in every aspect of our lives, with respect being doled out differentially along lines of race, class, ability, and body type, among others. These fears intersect with anxieties about being the “right” kind of fat person, the “right” kind of minority, the “right” kind of disabled person. And the “right” kind of person in any of these marginalized groups is always young and physically attractive, or has aged enough to be a cute old person.

There are times when we are allowed to have aged, but the act of aging itself, of being in transition between the states of “cute and young” and “cute and old,” is something to hide. And there is no guarantee that you will end up at “cute and old.” You are just as likely to end up not cute, facing the kind of pervasive ageism that leaves so many seniors socially isolated and struggling with intense loneliness and lack of intimacy.

Jonathan touches on this issue of hiding the ageing process when he says, “I think my fear is related to the way we treat our elders in our culture. Older folks aren’t valued. At best, we try to keep them out of sight until they die. At worst, we actively treat them poorly. Youth is idolized while age is seen as a liability. There are very few positive representations of age in our media. If there are famous old people, they became famous while they were young (and “beautiful”). Given how little we value our elders and given how much we prioritize youth over age, it’s REALLY hard to shake the internalized ageism that builds up. It’s a fear of becoming undesirable, of becoming forgotten, irrelevant.”

So, while many of these fears are related to appearances, they’re tied to fear of losing access to social supports and resources. Fears regarding the superficial physical changes that accompany aging are so deeply ingrained in our culture, and we grow up surrounded by a toxic fog of anti-ageing sentiment. This is exemplified in Rhonda’s statement that, “I hate that I’m looking like I’m aging … [I] shouldn’t feel that way ‘cause it was imposed upon me. But, still… I’m very afraid of it, and I hate it. Makes me sad. Not that aging was imposed upon me, but the belief that aging is bad and the feelings that go along with that.”

Michelle echoed Rhonda’s frustration with fearing ageing even though she recognizes that the fear doesn’t line up with how she wants to see herself. ““I like to think I don’t have a fear of aging, but.. I turned 40 and was shocked/hurt that my optometrist would even suggest after my eye exam that I needed bifocals. I literally needed a few weeks to digest that. I talked to an older friend that clearly had them, told me that sooner or later I will be tired of taking off and on my reading glasses. I had another friend get “progressives” and she told me that she seen a reduction in headaches.

I have accepted that I should get them, the blue filter, etc but after seeing the price, I had to start all over again with the “as if I need these” conversation I have been having with myself.” (Michelle is an amazing Indigenous woman running for Ward 10 in Calgary, Alberta. She’s worth supporting!)

Even when we recognize that the fear is imposed on us, and that the physical changes are inevitable, it’s difficult to move past them. Especially because while some of the changes related to ageing are aesthetic, many of them aren’t. Many people talked about their fears around losing physical ability.

Lyn said, “My body hurts, and creaks.. I’m sore every day. I’m trying to get fit, but it seems like an impossible goal due to all the things wrong with me, and the loss of youthful resiliency on top of it.”

Lost resiliency was also a concern for Rebecca, who said, “I am not afraid of this stage of aging (I’m 50). Nor am I afraid of dying (would prefer not to for at least 30 years or so). But I am afraid of how my body will break down, things I will lose of myself, in about 30 years. I realize today how much care I have to take of my body, how fragile it really is, and how if I don’t build resilience today, I’ll pay with pain tomorrow. And I’m afraid that the things I need to do to heal my body today, I just plain suck at doing. That dynamic of feeling not in control of my body because of the laziness of my mind is a hard one to navigate.”

And the idea that we can build resiliency and have it keep us safe from pain and degeneration isn’t always the case. Although there are things we can do at any age to help reduce pain and increase mobility, strength, and resilience, none of these protect us from illnesses.

Reina says, ”I didn’t used to be afraid of ageing before becoming chronically ill. Even though I don’t plan on having children, I figured I’d be able to do all of the things you’re supposed to do to provide for yourself in retirement and beyond. After becoming ill 5 years ago, I’m much more afraid of ageing. I’m unable to work due to ME/CFS. So financially getting older is scary, but also my health is poor now and I’m only 31. I worry that by the time I get much older my health will be horrid, I’ll be at much higher risk of bone density issues etc. I try my best to accept it and hope for the best, but it’s very scary sometimes.”

Emily also has a chronic (and degenerative) condition, and it impacts how she views ageing. “I call grey hairs wisdom strips and love getting older and feeling more content to be myself. The growing invisibility works well with my personality too. Could do without the degenerative disorder and I do fear increased pain/loss of mobility as it’s escalated a lot over last decade: definitely more scared of pain than death. If I could have the ageing without the pain, that would be ideal (ironically, EDS is joked about as having the face of a youngster and body of an OAP. Sometimes it would be handy to be aging more visibly as people often equate appearance of youth with health. ‘You don’t look sick.’) Fear of future instability can lead to anxiety in the present (I think finance feeds into this lots too – & fear of losing independence.) I try to channel it into doing physio to help delay progression/trying to do as much as I can when I can while I still have the option (with pacing – though getting that right can be a challenge with ever-changing condition).”

I, also, have a chronic pain condition that changed my perspective on ageing. Knowing that my body is already experiencing reduced mobility and flexibility does influence how much anxiety I feel about ageing.

Lost mobility is crushing, whether through chronic pain, illness, or ageing.

Nicole says, “I quite enjoy getting older now, as I feel like I’m at the stage where I’m becoming the person I want to be, someone I (mostly) like. But hell yes I fear becoming aged. I cringe at the thought that I, who lives so much for the outdoors and exploration, could be reduced to [a shuffling] level of mobility. I count the years off in my head, wondering if I’ll make it to 60 before I start to feel it? 70? My back already aches pretty much all the time. And most of all, I fear the dementia I’ve seen my grandma experience—not knowing anyone anymore, living by a routine that if just slightly altered, produces massive confusion and agitation. When the fear gets particularly bad I pump myself up by thinking about all the advances in technology we’re making, and try to pretend that somehow I’ll be able to afford it.”

Nicole expressed anxiety about the internalized ageism in her views, but like Rhonda and Michelle, and Jon and Collin, these fears become so deeply ingrained.

But Gina, who works in elder care, said that most of the people she works with are at peace with their reduced mobility, especially when they are able to access social supports. I can attest to the fact that, although I absolutely do still resent the aching pain when I forget my limits and am too active for too long, for the most part, I have adapted. My walks are slower and shorter, but they’re no less calming or enjoyable.

Erin touches on another common fear, the fear of missing out. She says, “I don’t love aging. As time passes, I feel like before I know it, all of it will be over. I want to savour the moments, but then feel sad that they’re gone. There’s so much I want to do and see before I’m done, and the older I get, the farther it all feels.”

There are a lot of things to fear. And a lot of us quietly holding that fear inside.

So, how do we self-care ourselves through these fears?

Fixating on the fear is not helpful, but neither is denying that it’s real and present. It can help to discuss our fears, in safe spaces and with people who won’t judge or dismiss us. Giving a name to your feelings can make it easier to understand them and reframe them.

Visualizing a variety of potential futures can also help. Confirmation bias is a real thing, and being open to possibilities other than the one you’re certain will happen can help you see the other possible outcomes (and the steps that might get you there) the you otherwise could miss. (This story about a 63 year old “accidental fashion icon” is one delightful exception to the trend. The fact that she’s white, thin, able-bodied, still quite conventionally attractive, and cisgender are all relevant intersections.)

Along the same track, it can be helpful to identify your fears, and then identify specific alternatives. For example – “I am afraid I will be old and alone” could be countered with “I can cultivate intentional community at any age.”

Another tool is to trace the roots of your fears. Are there specific messages – either from the wider culture, or from people in your life – that are informing your fear? Are they reasonable or realistic? What underlies the fears?

Consider getting to know some old people. Seek out and spend time with the elders in your community – especially if you share a marginalization. Community care is self-care, and spending time with elders can help shift your perspective on ageing from a mysterious and terrifying process that happens behind closed doors, to one that is part of our human experience.

As with anything to do with self-care, bring awareness, compassion, and intention to your practice and you’ll find the way through.

In our next post in this series, I’ll be writing about the positive sides of ageing, and the experiences and perspectives of people who are enjoying and looking forward to the process.

Further reading:

Sally Knocker’s 2012 report: Perspectives on Ageing: Lesbians, Gay Men, and Bisexuals.

Jess Dugan’s phenomenal project: To Survive on This Shore, interviews and portraits of transgender elders.

A PBS article about this study into the effects of racism on ageing, and how facing discrimination can cause people of colour to age more quickly: Racism may accelerate aging.

Fat Heffalump’s introduction post to her Plus 40 Fabulous contributions, about the intersection of fat acceptance and ageing.

Ashton Applewhite’s This Chair Rocks anti-ageism project includes a book, blog, and a “yo, is this ageist?” feature.

Lisa Wade’s short article (with a link to the original Sontag essay): Beauty and the Double Standard of Aging. (Note on both this article and the linked essay: cisnormative af.)

Debora Spar’s essay on feminism and beauty standards (also cisnormative, casually classist – as I searched for these “further reading” resources I found myself so deeply frustrated that the intersections of class, race, ability, orientation… even in writing that is meant to challenge and liberate, only the most privilege voices among a marginalized group are heard): Aging and My Beauty Dilemma

by Tiffany | Mar 22, 2017 | Health, Identity, Intersectionality, Patreon rewards, Personal, Plot twist, Possibilities Calgary

Possibilities Calgary is relaunching! Over the next couple weeks, you’ll see the About pages updating on the Facebook, the MeetUp, and Twitter. The posting for the first event will be going up tomorrow, and the event itself will happen in April. The first blog post will be up the first week of April. (You’ll even see a dedicated page on tiffanysostar.com, but not quite yet.)

We’re back!

First, some history. Then, some FAQs (the questions I asked myself most frequently when planning the relaunch).

Some history

Possibilities Calgary was founded in 2010 as the term-project in a Feminist Praxis course. I was in my second year of University, had recently come out as bisexual, and was searching for community. Searching… and searching… and searching…

At the time, there was no cohesive community in Calgary for bisexuals.

This is not unusual, since the bisexual community is chronically under-supported. The lack of support leads to, among other things, increased risk of intimate partner violence, under- and unemployment, significant rates of poverty, and poor mental health outcomes. (For a comprehensive look at the issues, read the 2011 Bisexual Invisibility Report, or, even better, read Shiri Eisner’s fantastic Bi: Notes for a Bisexual Revolution.)

I wanted community, and I couldn’t find it, so I built it. I had support from my Women’s Studies professor, Fiona Nelson. I met with community leaders to learn how to organize queer and feminist community in safe and effective ways. I had an amazing group of people to help me, and the Possibilities board was such a phenomenal support.

Possibilities ran for 5 years.

In that time, we expanded to include the asexual community (zero is not one, and so our ace friends fit under the non-monosexual umbrella comfortably!), and to include the transgender community (particularly the non-binary and transfeminine communities). There are trans members of every orientation – gender identity and sexual or romantic orientation are not the same things – but we found that those folks at the intersection of trans and non-monosexual identities were particularly and uniquely marginalized, and that Possibilities could help. For the last year of Possibilities, we had an offshoot community in Translations, which focused on transfeminine experiences.

We hosted three BiBQs during Calgary’s Pride week, and two Probabilities: Queer and Feminist Gaming Conventions. We also partnered with Calgary Outlink to host a monthly Community Café, which was a gender- and orientation-inclusive space. And, one of my personal highlights, we ran the UnConference series, bringing in speakers for multi-day events (including the hugely successful co-hosting of Courtney Trouble with the University of Calgary’s Institute for Gender Research).

Brittany says, “The BiBq was a super chill thing that I miss!” and Jocelyn confirms, “Get togethers involving food and convo” were a favourite feature.

Sid, a former board member says, “I got the opportunity not just to have my own need for support and community met but that I was also in an environment that gently encouraged me to explore how I related to other axes of oppression. Also, I always appreciated the constant supply of tea.”

Our intersectionality developed and grew over time, and although it was always imperfect, it was sincere. Rachel says, “I felt incredibly safe there.”

Michael, another former board member, says, “I really appreciated the sense of belonging to a community, and the ability to learn and grow from a group of amazing people with diverse life experiences.”

Scott, also a board member and facilitator, says, “I am not a word smith. I don’t have words beyond it was community for me. It felt inclusive and supportive.”

Jonathan, who helped me with the founding of the group, says, “Possibilities helped me learn more about how my newly discovered queer identity fit within a community. It enriched what would otherwise have been a much lonelier journey.”

It was good. It was so good. And it was needed.

But in 2015, a significant percentage of the board had moved on to new cities or new projects, and I burned out hard. Physically, emotionally, financially – I was tapped. The board members who remained continued to work hard, and new volunteers stepped up, but the organization was struggling. We couldn’t keep going. After major soul searching, we admitted the truth. Possibilities was on hiatus.

In 2016, I looked at restarting Possibilities, but realized that I didn’t have the resources to make it sustainable for myself. It hurt, but we stayed on hiatus.

But yesterday was the first day of Spring, 2017, and it was time for this seed to grow again. And so…

Some questions

Why am I relaunching Possibilities now?

Because it’s time. Because not having access to community causes harm, and because I have always believed that if you can do something good, then maybe you should do something good. (That maybe is super important – only you know what you can and can’t, or want to, do.) Because I miss this community. Because I miss being a community organizer. Because it’s time.

How am I going to avoid burning out again?

Friendship and magic? No, but seriously, I am hoping that two years of learning better self-care skills will help. I am also going to make it easier for people to support the work, and am tying it directly to my self-care and narrative work, which leads us to…

What will the relaunch involve?

I am making two commitments in this relaunch effort – one blog post or article per month, and one in-person “self-care for the b+ community” meeting. I don’t know if the BiBQ, or the gaming events, or the UnConference series, or any of the other major projects we were involved with will come back online, but I’m also not going to worry about that yet. By tying the work explicitly and intentionally to my self-care resource creation, this iteration of Possibilities fits beautifully into the work I’m doing for (and with) my Patreon. Which leads to the final question –

How can community members get involved?

If Possibilities is important to you, and you value having this community back up and running, please consider becoming a patron. That is the best way you can support this work, though I know not everyone is able. Possibilities discussion events, and the blog posts and articles, will be free for anyone, and the Patreon is what makes that possible. (Blog posts will also be available a week early for patrons, so, there’s that!) It makes me so happy to have come full circle, to have spiralled around to a new way to approach an old passion, and you can help ensure that the community stays active and vibrant going forward.

by Tiffany | Feb 26, 2017 | Coaching, Health, Identity, Intersectionality, Neurodivergence, Patreon rewards, Personal

Dressed up as a Gloom Fairy – one of the self-care strategies that got me through university.

This is a Patreon reward post. At $5 per month, you, too, can have a personalized post on the topic of your choice during your birthday month!

Red Davis (one of the first people to back my Patreon! *heart eyes*) is a current student and good friend. He asked for “a post relating to disabilities and mental health disorders within a university, professional, or social context; recurring themes of self-shame, embarrassment, and self-imposed solitude often debilitate many in higher learning or work situations.”

I will admit, I struggled with this post.

I wanted to write it, of course. Helping people navigate these hostile contexts while existing on the margins is exactly what I want to do in my coaching and self-care resource creation. Not only that, but it’s a reward that I’ve committed to providing for someone who is dipping into a tight student budget to support me, and make this work possible.

But, wow.

Every time I sat down to work on the post, my own feelings of shame, embarrassment, and self-imposed isolation flooded through me.

I remembered, specifically, one afternoon in 2012, standing in a hallway at the U of C, probably the Social Sciences building. One of the little ones, too brightly lit, with old computers on white tables, and plastic chairs, and a few students wandering. Wearing my winter jacket, dragging my backpack on wheels because the fibromyalgia no longer let me carry all those books, on my cell with the campus dental office cancelling an appointment because I was having a panic attack.

That panic attack cost me $100 in a late cancellation fee, and I never rebooked. Now, 5 years later, that memory still sparks shame and anger, and an icy-gut feeling of humiliation over the fact that my panic attacks cost me so much money at a time when I had so little, and that they kept me away from necessary healthcare. (And they have continued to do so! That appointment would have been my first visit to a dentist in years, and when I said I never rebooked, I mean that I never rebooked. It’s on my to-do list for this week. Seriously. I’m gonna do it. For real. I swear.)

The memory is about the money, the shame of “wasting” money on a “ridiculous” mental health issue. Sort of. Maybe. I mean, the money is part of it.

But it’s also about the voice on the other end of the phone, the impatience and irritation of the receptionist, and the feeling of shame when I started to cry and she cut me off. “Sorry, no exceptions to the cancellation fee, if you were going to be unable to make it, you should have called yesterday.”

These feelings are deeply physical. Shame, humiliation, fear – these are all visceral reactions, gut feelings. 5 years after that phone call, I still feel the twisting in my belly as the shame winds through me.

And when Red touches on self-imposed solitude, this twisting shame belly is part of that. Shame, after all, is an isolating emotion. It pushes us away from each other, drags us off into dark corners to hide ourselves.

How do we reach out when we are captives of our shame?

But shame is not the only factor.

Time and energy are also factors.

How do we maintain our social circle when disabilities make the work of school or professional life take longer, and take more out of us?

When fibromyalgia arrived on the scene, stealing my energy and my reading comprehension, and for one horrific semester, my ability to write… everything took longer. Everything took longer. Crossing the street took longer! Reading a paper took longer, and took more out of me. I was tired at the end of a page, exhausted at the end of a chapter. I deferred coursework, missed deadlines, spent endless hours in doctors’ offices and at the disability resource centre – hours that were then not available for schoolwork or paying work or socializing.

The anger at no longer being able to operate as I had was immobilizing, and embarrassing. The shame was overwhelming. The exhaustion was beyond comprehension. It triggered a depression… or did the depression precede the pain? Those years are a dark smear of distress across my memory.

How do you make it through post-secondary or professional contexts when dealing with disabilities or mental health issues?

How do you survive?

How do you continue, knowing that your brain and your body are working against your ability to fit into these contexts?

In 2013, I did my first Year of Self-Care.

I needed it. Even through the blur of my distress, I knew that I needed it. I was falling apart. I was a wreck – physically, emotionally, mentally, financially.

I don’t honestly remember much from the beginning of that project.

I know that I was desperate.

When I was 18, at another desperate point in my life, I had done a Year of Independence in an effort to heal some relationship trauma. It was one of the highlights of my youth, remains one of my favourite experiences. I leaned on that, and set out some plans.

It wasn’t easy.

<blockquote class="twitter-tweet" data-lang="en"><p lang="en" dir="ltr">Working on a <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/YearofSelfCare?src=hash">#YearofSelfCare</a> mind map. Seeing all of my projects fill up the white space, my anxiety levels make sense. ...</p>— Tiffany Sostar (@academictivist) <a href="https://twitter.com/academictivist/status/345648578791882754">June 14, 2013</a></blockquote><!-- [et_pb_line_break_holder] --><script async src="//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script><!-- [et_pb_line_break_holder] -->

But one of my founding principles for that year was compassion for myself. The act of compassion and care, even when the feeling was unattainable.

<blockquote class="twitter-tweet" data-lang="en"><p lang="en" dir="ltr">Thinking about <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/YearofSelfCare?src=hash">#YearofSelfCare</a> tools and processes. Thinking about compassion (for self and others) as an active, intentional practice.</p>— Tiffany Sostar (@academictivist) <a href="https://twitter.com/academictivist/status/345202208616361984">June 13, 2013</a></blockquote><!-- [et_pb_line_break_holder] --><script async src="//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script><!-- [et_pb_line_break_holder] -->

I needed to start there, because at the time, my body and my brain felt like my enemies. I think that’s a common experience for people dealing with disability or neurodivergence. It’s hard to practice effective and sustainable self-care when you feel like your own enemy.

The Year of Self-Care included a lot of hit-and-miss experimentation.

During that year, I discovered how much I enjoy the ritual of tea, and that’s the year I learned to make London Fogs. I still make amazing London Fogs (though not as often as I used to – I need a new milk frother).

I also experimented much more intentionally with using outfits as armour and as a self-affirming tool. Gloom Fairy, The Pirate King, and Elf Commander all have roots in those Year of Self-Care experiments.

How do you continue, knowing that your brain and your body are working against your ability to fit into these contexts?

It was the year that the Wall of Self-Care went up, white boards with anxiety bubbles, and self-care lists, and my inspiration board.

It was the year I learned to swim, in order to challenge a phobia, and get my fibromyalgia pain under control, and prove to myself that I could.

It was the year of endless struggle, and I was lucky because it was also the year of infinite support.

It was a hard year. But it was a good year.

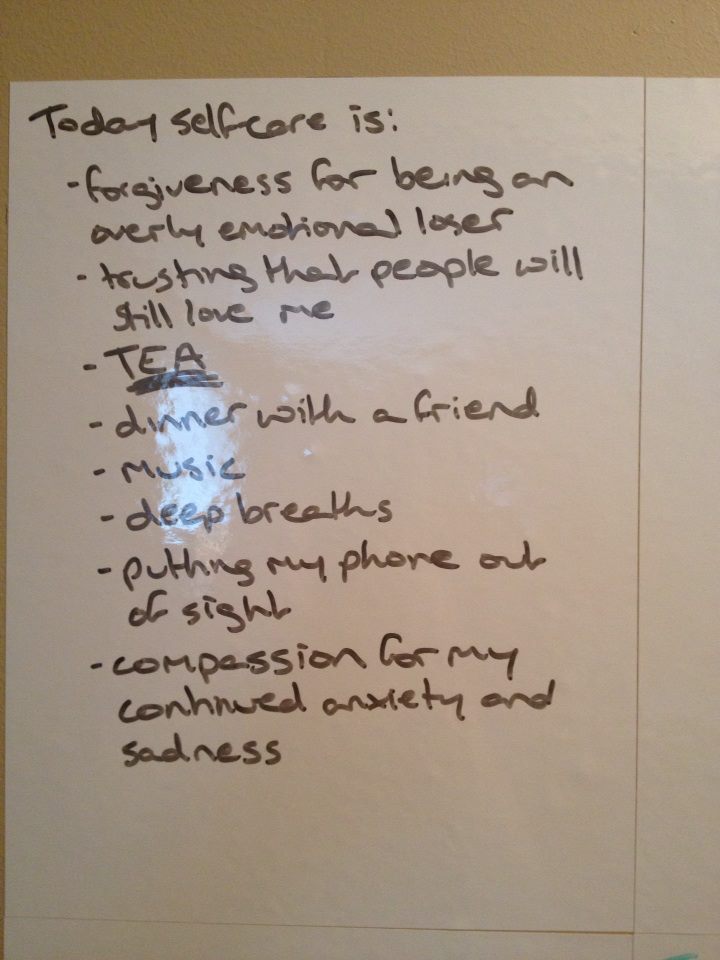

A list of self-care to-do items posted on Facebook in 2013 with the comment: This afternoon took a sudden, unexpectedly intense turn for the worse, so I hung up some stick-on white boards (expanding my wall of self-care) and made a list. Intentional self-care! For those of us whose default position is ‘the unfortunate person crying in the stairwell.’ Sigh.

A badge given to me by my friend Patti when I successfully managed to tread water.

A love note from my little niephling.

The biggest lesson from that year was that self-care is fucking hard. It’s hard. Making a cup of tea when you’re exhausted, and ashamed, and embarrassed, and feeling lonely despite your community – it’s hard. Reaching out for help? Holy shit, that is not easy. Doing anything other than wallowing is just really hard.

Making choices intentionally, and choosing compassion and care, it takes effort. And you fuck up, a lot. You fuck up all the time. It took a year and half to complete my Year of Self-Care (my “Year of Whatever”s are almost always a year and a half – either the new year to my birthday the next year, or my birthday to the new year. I like some wiggle room.)

In that year and a half, I made plans and failed to complete them. I made the same plan again and failed. I made a slightly different plan and failed in a different way. I made a totally new plan and still failed. I tried again and failed. I made schedules and failed to stick to them. I set goals and didn’t meet them. I dropped more balls than I kept in the air, and that’s okay.

That’s okay.

It doesn’t feel okay at the time. It feels awful. But that process of failing at self-care is an important part of the journey. Self-care has to involve deep compassion for your broken, aching self. It can’t all be celebrations and successes. It won’t be. If it was, you wouldn’t need it so badly.

In order to get to a place where you have effective and sustainable self-care practices in place, you need to go through the process of pushing against the resistance. The internal resistance, sure. The shame, the fear, the feelings of selfishness and the anxiety over failure. But mostly, mostly, the external resistance.

You have to smash your fist against the cost of self-care. That $100 penalty for a panic attack. The cost of admission to the pool. The cost of white boards. The cost of missed work hours. The cost of healthcare, even here in Canada. The cost of therapy. The cost of nourishing food. These costs that you cannot always afford. You have to run into that wall over and over and over until you find ways under, or through, or around it. And sometimes you don’t. Sometimes you can’t. Self-care cannot belong only to the financially secure. Those of us who are disabled or neurodivergent or otherwise marginalized are much more likely to be dealing with economic insecurity, to be living in poverty, to be stretched too thin, to have ends that not only don’t meet, they don’t even make eye contact. We deserve self-care, too. But it takes time to find those tools, because it’s much quicker and easier when you do have the money for it.

And you have to smash your fist against the unreasonable and inhumane demands of post-secondary and professional institutions. Deadlines and dress codes and disdain. I dropped a course I really loved because handwritten notes were mandatory for a huge percentage of the grade, but my hands hurt too much to write long-hand. More bitterly, I dropped out of the Arts and Sciences Honours Academy because the professor in third year required mandatory attendance, with no more than two exceptions for medical issues. “Breathe deeply and drink a mug of tea” doesn’t wash the salt from those wounds. Getting to sustainable self-care means feeling that sting, doing what you can with the resources that you have, trying to find ways around it. Finding the understanding professors, begging with the disability resource centre, paying the $25 to have a doctor write a letter saying that yes, you really do need these accommodations. It takes time, and it takes energy, and it takes a lot of permission to just be angry and bitter on your way to being calm.

And doctors… another wall, another round of smashing and smashing and smashing until you find the way through. Get the diagnosis, get the prescription, get the help. Or, sometimes, you don’t. Find other ways to cope.

The systems are not built for us.

It hurts to contort ourselves to fit within them.

That pain is real. That injustice is real.

There are ways forward. My Year of Self-Care made a huge difference for me. I’m not meaning to downplay the importance of doing that gritty work of developing more wholehearted self-care and self-storying strategies. But I get frustrated at resources that don’t acknowledge how hard this is, and how much the odds are stacked against anyone who differs from the straight, white, cisgender, able-bodied, neurotypical, class privileged norm.

When I started working on this post, I did what I always do at the beginning of a writing project. I opened a new Chrome window and I googled this shit out of my topic. I started with “self-care for students” and I found dozens of posts. Every post-secondary institution seems to have some kind of self-care guide for students. (Perhaps because post-secondary institutions are set up in such a way that any student who doesn’t have an extremely solid base of socioeconomic stability is pretty much fucked when it comes to mental, emotional, and physical health? Dunno, just a theory.)

These resources place a huge emphasis the individual doing everything possible to maintain their self-care

This resource from the University of Michigan is a perfect example.

“Taking steps to develop a healthier lifestyle can pay enormous dividends by reducing stress and improving your physical health, both of which can improve your mental health as well. Students with mental health disorders are at a higher risk for some unhealthy behaviors. You may find it challenging to make healthy choices and manage your stress effectively while in college. This section of the website will help you find ways to take care of your health, which can help you to feel better and prevent or manage your mental health symptoms.”

Look at that language! You’re at higher risk for unhealthy behaviours. You may find it challenging to make healthy choices. Gross. Gross! There is nothing there about how the structures and systems and expectations and normativity around you are the source of that distress, and put stumbling blocks in front of your movements towards “health.” It pushes the responsibility entirely onto the student who is struggling, and then wipes its hands clean. There’s good advice in that resource, but it comes in bitter packaging.

Even posts like this assume that the identity of “student” is also normatively able-bodied and neurotypical.

“College students’ ability to deny basic needs like sleep can oftentimes seem like a badge of honor proving we are reckless and young. At my school, it can seem like a competition to see who can stay up longer to study, and pulling all-nighters seems like proof we are true UChicago students. One’s talk of working grueling hours in the library is met with solidarity and sympathetic laughter, while taking a break or decreasing course load seems to be associated with weakness.”

College students who can’t meet that expectation are, I guess, not “true students.” When the article concludes that:

“If we want to improve our psychological and emotional health, college students could perhaps benefit from changing their mindsets and relationships to work. Taking breaks and letting our minds rest could be an effective strategy for achieving our goals in the long run, because stress or lack of sleep can hinder productivity. Maybe the next time a friend bemoans having to pull an all-nighter for a class, we can think about how our response may perpetuate a culture that idolizes self-destructive behavior. Perhaps rather than laughing or saying that we understand their struggle, we can gently encourage them to take a break. Or, if it’s you who’s putting in those late-night hours, maybe go home for sleep rather than the campus cafe for coffee. You deserve it. You matter, and your health matters.”

There is still the assumption that this is a choice, and that is not the case for every student.

So, in conclusion, it’s fucking hard. And it’s not your fault. And you can figure it out, but it will take time. And you will continue to run into walls.

<blockquote class="twitter-tweet" data-lang="en"><p lang="en" dir="ltr">More pain = less sleep = more pain = less sleep. The point of the <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/yearofselfcare?src=hash">#yearofselfcare</a> is to become my own ally and friend. Not easy!</p>— Tiffany Sostar (@academictivist) <a href="https://twitter.com/academictivist/status/385261628897239040">October 2, 2013</a></blockquote><!-- [et_pb_line_break_holder] --><script async src="//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script><!-- [et_pb_line_break_holder] -->

Being your own ally is not easy. It’s even harder when there are complicating factors like disability, pain, depression, anxiety, or other chronic issues that aren’t going away. And it’s even harder when you’re in hostile environments like many post-secondary and professional contexts.

But I believe in you. There is a way forward. There is always a way forward.