Dressed up as a Gloom Fairy – one of the self-care strategies that got me through university.

This is a Patreon reward post. At $5 per month, you, too, can have a personalized post on the topic of your choice during your birthday month!

Red Davis (one of the first people to back my Patreon! *heart eyes*) is a current student and good friend. He asked for “a post relating to disabilities and mental health disorders within a university, professional, or social context; recurring themes of self-shame, embarrassment, and self-imposed solitude often debilitate many in higher learning or work situations.”

I will admit, I struggled with this post.

I wanted to write it, of course. Helping people navigate these hostile contexts while existing on the margins is exactly what I want to do in my coaching and self-care resource creation. Not only that, but it’s a reward that I’ve committed to providing for someone who is dipping into a tight student budget to support me, and make this work possible.

But, wow.

Every time I sat down to work on the post, my own feelings of shame, embarrassment, and self-imposed isolation flooded through me.

I remembered, specifically, one afternoon in 2012, standing in a hallway at the U of C, probably the Social Sciences building. One of the little ones, too brightly lit, with old computers on white tables, and plastic chairs, and a few students wandering. Wearing my winter jacket, dragging my backpack on wheels because the fibromyalgia no longer let me carry all those books, on my cell with the campus dental office cancelling an appointment because I was having a panic attack.

That panic attack cost me $100 in a late cancellation fee, and I never rebooked. Now, 5 years later, that memory still sparks shame and anger, and an icy-gut feeling of humiliation over the fact that my panic attacks cost me so much money at a time when I had so little, and that they kept me away from necessary healthcare. (And they have continued to do so! That appointment would have been my first visit to a dentist in years, and when I said I never rebooked, I mean that I never rebooked. It’s on my to-do list for this week. Seriously. I’m gonna do it. For real. I swear.)

The memory is about the money, the shame of “wasting” money on a “ridiculous” mental health issue. Sort of. Maybe. I mean, the money is part of it.

But it’s also about the voice on the other end of the phone, the impatience and irritation of the receptionist, and the feeling of shame when I started to cry and she cut me off. “Sorry, no exceptions to the cancellation fee, if you were going to be unable to make it, you should have called yesterday.”

These feelings are deeply physical. Shame, humiliation, fear – these are all visceral reactions, gut feelings. 5 years after that phone call, I still feel the twisting in my belly as the shame winds through me.

And when Red touches on self-imposed solitude, this twisting shame belly is part of that. Shame, after all, is an isolating emotion. It pushes us away from each other, drags us off into dark corners to hide ourselves.

How do we reach out when we are captives of our shame?

But shame is not the only factor.

Time and energy are also factors.

How do we maintain our social circle when disabilities make the work of school or professional life take longer, and take more out of us?

When fibromyalgia arrived on the scene, stealing my energy and my reading comprehension, and for one horrific semester, my ability to write… everything took longer. Everything took longer. Crossing the street took longer! Reading a paper took longer, and took more out of me. I was tired at the end of a page, exhausted at the end of a chapter. I deferred coursework, missed deadlines, spent endless hours in doctors’ offices and at the disability resource centre – hours that were then not available for schoolwork or paying work or socializing.

The anger at no longer being able to operate as I had was immobilizing, and embarrassing. The shame was overwhelming. The exhaustion was beyond comprehension. It triggered a depression… or did the depression precede the pain? Those years are a dark smear of distress across my memory.

How do you make it through post-secondary or professional contexts when dealing with disabilities or mental health issues?

How do you survive?

How do you continue, knowing that your brain and your body are working against your ability to fit into these contexts?

In 2013, I did my first Year of Self-Care.

I needed it. Even through the blur of my distress, I knew that I needed it. I was falling apart. I was a wreck – physically, emotionally, mentally, financially.

I don’t honestly remember much from the beginning of that project.

I know that I was desperate.

When I was 18, at another desperate point in my life, I had done a Year of Independence in an effort to heal some relationship trauma. It was one of the highlights of my youth, remains one of my favourite experiences. I leaned on that, and set out some plans.

It wasn’t easy.

But one of my founding principles for that year was compassion for myself. The act of compassion and care, even when the feeling was unattainable.

I needed to start there, because at the time, my body and my brain felt like my enemies. I think that’s a common experience for people dealing with disability or neurodivergence. It’s hard to practice effective and sustainable self-care when you feel like your own enemy.

The Year of Self-Care included a lot of hit-and-miss experimentation.

During that year, I discovered how much I enjoy the ritual of tea, and that’s the year I learned to make London Fogs. I still make amazing London Fogs (though not as often as I used to – I need a new milk frother).

I also experimented much more intentionally with using outfits as armour and as a self-affirming tool. Gloom Fairy, The Pirate King, and Elf Commander all have roots in those Year of Self-Care experiments.

How do you continue, knowing that your brain and your body are working against your ability to fit into these contexts?

It was the year that the Wall of Self-Care went up, white boards with anxiety bubbles, and self-care lists, and my inspiration board.

It was the year I learned to swim, in order to challenge a phobia, and get my fibromyalgia pain under control, and prove to myself that I could.

It was the year of endless struggle, and I was lucky because it was also the year of infinite support.

It was a hard year. But it was a good year.

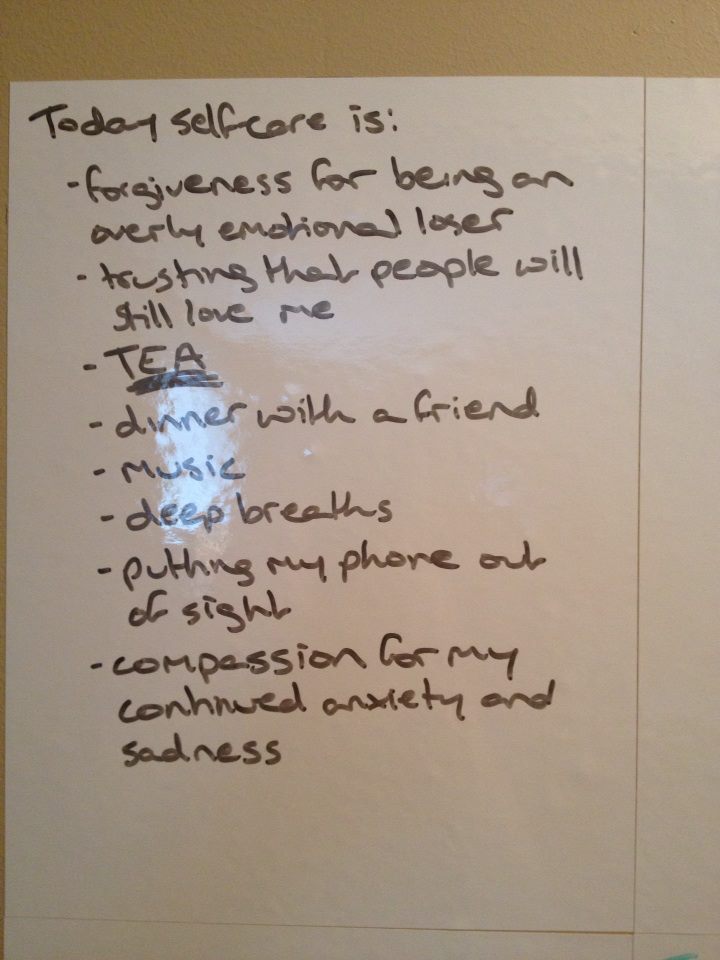

A list of self-care to-do items posted on Facebook in 2013 with the comment: This afternoon took a sudden, unexpectedly intense turn for the worse, so I hung up some stick-on white boards (expanding my wall of self-care) and made a list. Intentional self-care! For those of us whose default position is ‘the unfortunate person crying in the stairwell.’ Sigh.

A badge given to me by my friend Patti when I successfully managed to tread water.

A love note from my little niephling.

The biggest lesson from that year was that self-care is fucking hard. It’s hard. Making a cup of tea when you’re exhausted, and ashamed, and embarrassed, and feeling lonely despite your community – it’s hard. Reaching out for help? Holy shit, that is not easy. Doing anything other than wallowing is just really hard.

Making choices intentionally, and choosing compassion and care, it takes effort. And you fuck up, a lot. You fuck up all the time. It took a year and half to complete my Year of Self-Care (my “Year of Whatever”s are almost always a year and a half – either the new year to my birthday the next year, or my birthday to the new year. I like some wiggle room.)

In that year and a half, I made plans and failed to complete them. I made the same plan again and failed. I made a slightly different plan and failed in a different way. I made a totally new plan and still failed. I tried again and failed. I made schedules and failed to stick to them. I set goals and didn’t meet them. I dropped more balls than I kept in the air, and that’s okay.

That’s okay.

It doesn’t feel okay at the time. It feels awful. But that process of failing at self-care is an important part of the journey. Self-care has to involve deep compassion for your broken, aching self. It can’t all be celebrations and successes. It won’t be. If it was, you wouldn’t need it so badly.

In order to get to a place where you have effective and sustainable self-care practices in place, you need to go through the process of pushing against the resistance. The internal resistance, sure. The shame, the fear, the feelings of selfishness and the anxiety over failure. But mostly, mostly, the external resistance.

You have to smash your fist against the cost of self-care. That $100 penalty for a panic attack. The cost of admission to the pool. The cost of white boards. The cost of missed work hours. The cost of healthcare, even here in Canada. The cost of therapy. The cost of nourishing food. These costs that you cannot always afford. You have to run into that wall over and over and over until you find ways under, or through, or around it. And sometimes you don’t. Sometimes you can’t. Self-care cannot belong only to the financially secure. Those of us who are disabled or neurodivergent or otherwise marginalized are much more likely to be dealing with economic insecurity, to be living in poverty, to be stretched too thin, to have ends that not only don’t meet, they don’t even make eye contact. We deserve self-care, too. But it takes time to find those tools, because it’s much quicker and easier when you do have the money for it.

And you have to smash your fist against the unreasonable and inhumane demands of post-secondary and professional institutions. Deadlines and dress codes and disdain. I dropped a course I really loved because handwritten notes were mandatory for a huge percentage of the grade, but my hands hurt too much to write long-hand. More bitterly, I dropped out of the Arts and Sciences Honours Academy because the professor in third year required mandatory attendance, with no more than two exceptions for medical issues. “Breathe deeply and drink a mug of tea” doesn’t wash the salt from those wounds. Getting to sustainable self-care means feeling that sting, doing what you can with the resources that you have, trying to find ways around it. Finding the understanding professors, begging with the disability resource centre, paying the $25 to have a doctor write a letter saying that yes, you really do need these accommodations. It takes time, and it takes energy, and it takes a lot of permission to just be angry and bitter on your way to being calm.

And doctors… another wall, another round of smashing and smashing and smashing until you find the way through. Get the diagnosis, get the prescription, get the help. Or, sometimes, you don’t. Find other ways to cope.

The systems are not built for us.

It hurts to contort ourselves to fit within them.

That pain is real. That injustice is real.

There are ways forward. My Year of Self-Care made a huge difference for me. I’m not meaning to downplay the importance of doing that gritty work of developing more wholehearted self-care and self-storying strategies. But I get frustrated at resources that don’t acknowledge how hard this is, and how much the odds are stacked against anyone who differs from the straight, white, cisgender, able-bodied, neurotypical, class privileged norm.

When I started working on this post, I did what I always do at the beginning of a writing project. I opened a new Chrome window and I googled this shit out of my topic. I started with “self-care for students” and I found dozens of posts. Every post-secondary institution seems to have some kind of self-care guide for students. (Perhaps because post-secondary institutions are set up in such a way that any student who doesn’t have an extremely solid base of socioeconomic stability is pretty much fucked when it comes to mental, emotional, and physical health? Dunno, just a theory.)

These resources place a huge emphasis the individual doing everything possible to maintain their self-care

This resource from the University of Michigan is a perfect example.

“Taking steps to develop a healthier lifestyle can pay enormous dividends by reducing stress and improving your physical health, both of which can improve your mental health as well. Students with mental health disorders are at a higher risk for some unhealthy behaviors. You may find it challenging to make healthy choices and manage your stress effectively while in college. This section of the website will help you find ways to take care of your health, which can help you to feel better and prevent or manage your mental health symptoms.”

Look at that language! You’re at higher risk for unhealthy behaviours. You may find it challenging to make healthy choices. Gross. Gross! There is nothing there about how the structures and systems and expectations and normativity around you are the source of that distress, and put stumbling blocks in front of your movements towards “health.” It pushes the responsibility entirely onto the student who is struggling, and then wipes its hands clean. There’s good advice in that resource, but it comes in bitter packaging.

Even posts like this assume that the identity of “student” is also normatively able-bodied and neurotypical.

“College students’ ability to deny basic needs like sleep can oftentimes seem like a badge of honor proving we are reckless and young. At my school, it can seem like a competition to see who can stay up longer to study, and pulling all-nighters seems like proof we are true UChicago students. One’s talk of working grueling hours in the library is met with solidarity and sympathetic laughter, while taking a break or decreasing course load seems to be associated with weakness.”

College students who can’t meet that expectation are, I guess, not “true students.” When the article concludes that:

“If we want to improve our psychological and emotional health, college students could perhaps benefit from changing their mindsets and relationships to work. Taking breaks and letting our minds rest could be an effective strategy for achieving our goals in the long run, because stress or lack of sleep can hinder productivity. Maybe the next time a friend bemoans having to pull an all-nighter for a class, we can think about how our response may perpetuate a culture that idolizes self-destructive behavior. Perhaps rather than laughing or saying that we understand their struggle, we can gently encourage them to take a break. Or, if it’s you who’s putting in those late-night hours, maybe go home for sleep rather than the campus cafe for coffee. You deserve it. You matter, and your health matters.”

There is still the assumption that this is a choice, and that is not the case for every student.

So, in conclusion, it’s fucking hard. And it’s not your fault. And you can figure it out, but it will take time. And you will continue to run into walls.

Being your own ally is not easy. It’s even harder when there are complicating factors like disability, pain, depression, anxiety, or other chronic issues that aren’t going away. And it’s even harder when you’re in hostile environments like many post-secondary and professional contexts.

But I believe in you. There is a way forward. There is always a way forward.