by Tiffany | Aug 20, 2018 | Identity, Neurodivergence, Patreon rewards

Image description: A notecard hanging from a string. Text reads: Do you like me?

(This is an edited and expanded version of a post that was shared with my patrons one week early. If you’d like early access to my posts, and the ability to suggest changes or make comments before they go up on my blog, consider backing my Patreon!)

On April 9, 2018, I wrote to Jonathan, who has been a patron since the beginning of the project (and a partner for 10 years!), “Your birthday is coming! What do you want me to write about this year?”

He wrote back almost immediately, “Caring what others think.”

I like decisiveness.

And I like this topic.

He continued:

Just to expand on the topic…

The shame I feel over caring what other people think is difficult to navigate. When I was a kid I was told, over and over again, that I was just supposed to be myself and not care what other people think.

That sentiment really oversimplifies things. On the one hand, I get it. Caring too much about what other people think can really paralyze you. It gives other people a lot of power over you. It creates a lot of pressure, sometimes, to do things that you wouldn’t otherwise do. It stunts your ability to develop your own ideas, your own interests and your own destiny.

Caring what others think is seen as a sign of weakness. It means you don’t have your own personality; you’re two-faced; you lack principle and your own moral compass. We don’t trust people who care what other people think because we think of those people as fake. Caring what others think “too much” can be inaccurately pathologized as mental disorders such as paranoia, bi-polar and attention seeking disorders.

On the other hand, all of the non-vocal messaging you get is that it’s actually really, really important to worry about what other people think. Your social networks depend on what other people think about you. Your job depends on what other people think about you. Your ability to access resources depends on what other’s think of you.

It’s a cruel myth that only the weak care what other’s think. Corporations literally invest billions in controlling what other people think about them. Politicians direct a considerable amount of their power and capital towards carefully curating their public image. Many of our public institutions operate entirely based on people’s impression of the institution.

Clearly, it’s important to carefully balance the stock you place in what other’s think and your own self-confidence and commitment to be “true to yourself” despite social pressure. It’s complicated.

I’m out of balance over it. Caring what other’s think causes me anxiety. When I feel like someone is upset or angry with me I fixate on that. When I feel like someone thinks poorly of me or has a negative impression of my skill set it completely eats away at me. It makes conflict resolution very difficult for me to manage sometimes. It also means that I sometimes have a hard time being honest and authentic not only with the people around me but also with myself. I’m struggling to find a way to bring that into balance. I think, over the years, I’ve developed real strengths because of my obsession with what other’s think. I’m very keen to non-verbal communication and a pretty empathetic person. I’ve learned a lot about social cues and can pick out social patterns better than most. Meeting expectations is important to me and, when I have proper balance in my life, I’m pretty good at exceeding expectations because I care what other people think. I think my compassion also stems from caring and that’s not something I care to lose.

So, I think the concept of caring what others think is one that could really benefit from some exploration. It’s one of those deceptively simple ideas that actually has a lot of layers and a lot of depth to it.

After this post was suggested, this topic kept coming up. And it kept coming up in ways that really supported Jonathan’s insight into the way this idea “has a lot of layers and a lot of depth to it.”

It showed up in narrative therapy sessions, where one of my community members identified “caring what others think” as something that is both a cherished characteristic that allows them to bring empathy and compassion into their relationships, and also something that keeps them from acting on their own desires and needs.

Then it showed up in that same way for another community member. They care a lot about what other people think of them, and it’s both something they value in themselves and also something that they experience as a block or obstacle when trying to care for their own needs.

Then it showed up in a similar was for a third community member, who also talked about this particular experience in work contexts, where caring about what coworkers think is a skill that keeps them from oversharing and allows them to maintain boundaries, but also has them feeling isolated sometimes.

This idea of “caring what others think” became the basis of the “too much of a good thing” project that I’m undertaking as part of my master of narrative therapy and community work program (Note: I am still looking for participants for the project, so if it sounds interesting to you, get in touch!) Because the idea was growing so much, it seemed impossible to come back to this original writing prompt. I felt that I needed to get the whole project done in order to present something worthwhile.

(Sounds a bit like I’m caring about what others think of my writing, right? This shows up frequently for me, and it means I generally publish work that I’m proud of, and I don’t share nearly as much as I would like to. For the next while, I’m working on challenging this urge towards perfection and I’ll be sharing things that are a little less intensely edited. We’ll see how it goes!)

In May, this idea of “caring what others think” showed up in my own life in a big way when I was suddenly thrown headfirst into a situation where “what people think about me” became something I had to care about intensely. I was feeling (and being) observed and critiqued in personal and impactful ways. Writing about this topic felt more and more impossible.

It was everywhere! Overwhelming!

I decided to come back to this post, even though the “too much of a good thing” project is still underway, because “caring what others think” seems critical on its own. Although this topic fits within a larger framework, it deserves its own examination and exploration. As Jonathan pointed out, “it’s a cruel myth that only the weak care what other people think.” But that myth is everywhere. It’s one that impacts most of us in one way or another.

Ask the Internet

If you google “caring what other people think,” you’re likely to get a whole bunch of results with instructions for how to stop, and often with language that pathologizes or shames people who do care what other people think.

In one post on Psychology Today, the author writes, “One of our more enduring social fallacies is the idea that what others think of us actually matters. While this notion clearly has primal evolutionary roots, its shift from survival instinct to social imperative has become one of our greatest obstacles to self-acceptance.”

I have questions about this.

Is it a fallacy that what others think of us actually matters?

What my boss thinks of me matters to my employment.

It matters what the community members who consult with me think of me. It impacts my efficacy as a narrative therapist. Some research suggests that the best indicator of success in the therapeutic relationship is the “therapeutic alliance” (meaning the positive relationship between the therapist and the person consulting them). One review of the literature found that multiple studies “indicated that the quality of the alliance was more predictive of positive outcome than the type of intervention.” If that’s the case, it matters a whole lot to my work as a narrative therapist what people think!

I also wonder about the “primal evolutionary roots” of caring what people think. I am skeptical of most evolutionary psychology, given its many problems. (For one view on these problems, this problematically hetero- and cisnormative Scientific American article is a good place to start.) I particularly question this “primal” nature of the issue given the very contemporary context within which so many of us do care what others think.

For marginalized individuals especially, caring what people think can keep us alive. Caring what others think means knowing, deeply and intimately, what the dominant expectations are so that we can do our best to adapt to them.

For neurodivergent folks on the autism spectrum, caring what others think is part of the training – look at the language used in the popular Social Thinking program. (Content note on this link at the Social Thinking site for unsettling language about autistic kids. If you just want to read critiques, many of them by autistic writers, this facebook thread is full of information, but also upsetting to read.) “Expected” and “unexpected” behaviours, where “unexpected” means that the child hasn’t responded to the “hidden rule” and could be making people “uncomfortable.” Talk about teaching kids to care what others think!

On a more positive note, caring what other people thinks can foster a sense of being “accountable to the whole,” to quote my friend and mentor Stasha. This accountability to the whole means that we maintain an awareness of how our actions impact each other, and when Stasha made this comment I wondered whether a more intentional and compassionate relationship with the idea of caring what people think might be one way to challenge the individualism and isolation that our current capitalist context enforces.

Another article, this time from Lifehack, quotes Lao Tzu, “Care about what other people think and you will always be their prisoner” and concludes, “Once you give up catering to other people’s opinion and thoughts, you will find out who you truly are, and that freedom will be like taking a breath for the first time.”

Again, I have questions.

The Socially Constructed Self

Is “who I truly am” really something that happens entirely in isolation, entirely internal and apart from other people and what they think? I don’t think that it is.

I brought this question to one of the narrative therapy groups I’m part of, and I was very worried about what the group would think of me. I wrote, “This is an absolutely ridiculous question because I feel like I have read *at least* seven different version of this idea, but I’ve been searching and failing, so, halp?! I am looking for a good, comprehensive-ish, ideally readable-by-non-academic-audiences (but I’ll take an academic article also) resource on the idea of the self being shaped by context and relationships.”

I felt ashamed of the fact that I needed help, but the responses that I got were incredibly validating!

One person commented to say they were following, and I said, “You have no idea how relieving it is to realize I’m not alone in this.” They replied, “I think one of the most dangerous things a therapist can do is let their ego in the way of asking questions – well, that’s what I tell myself as I manage my “imposter syndrome” ?”

Someone else said, “So glad you asked!! I need just the thing and didn’t think of asking here!”

So many of us caring so much what each other would think, and finding solidarity and companionship in realizing that we’re not alone in it. Although the way that anticipatory shame keeps us silent is a problem, I think that the shared experience is valuable. And normal. In that group, we are all either practicing therapists or students of narrative therapy or both, and we still care deeply about what other people will think of us. We can respond to the ways in which this caring becomes a problem without demanding that we suddenly cease caring entirely. And without accepting that we are somehow incomplete because of it!

One of the responses was from someone linking me to this resource by Ken Gergen.

Gergen’s “Orienting Principles” are here (from the link – I highly recommend following the link and listening to his talk!):

We live in world of meaning. We understand and value the world and ourselves in ways that emerge from our personal history and shared culture.

Worlds of meaning are intimately related to action. We act largely in terms of what we interpret to be real, rational, satisfying, and good. Without meaning there would be little worth doing.

Worlds of meaning are constructed within relationships. What we take to be real and rational is given birth in relationships. Without relationship there would be little of meaning.

New worlds of meaning are possible. We are not possessed or determined by the past. We may abandon or dissolve dysfunctional ways of life, and together create alternatives.

To sustain what is valuable, or to create new futures, requires participation in relationships. If we damage or destroy relations, we lose the capacity to sustain a way of life, and to create new futures.

When worlds of meaning intersect, creative outcomes may occur. New forms of relating, new realities, and new possibilities may all emerge.

When worlds of meaning conflict, they may lead to alienation and aggression, thus undermining relations and their creative potential.

Through creative care for relationships, the destructive potentials of conflict ma be reduced, or transformed.

Two things jump out at me particularly: that worlds of meaning are created within relationships (which I take as a direct contradiction of the idea that we “find out who we truly are” only outside of relationship and others influence), and that together we can create alternatives.

Individualism

On a similar note, I also have questions about why freedom is so individualized, if there is so much creative potential in relationships.

Of course, these articles that advise us on how to stop caring what others think of us aren’t suggesting that people shouldn’t have relationships, and treating them as if they are would be setting up a straw man that isn’t there. However, I think that there is an individualist discourse present in these articles that suggests that we can have relationships without caring what the people in our relationships think of us, and I think that discourse invites a lack of accountability and collaboration, and suggests that there is a core self that exists apart from the self within relationships. I disagree with this idea.

Melanie Grier, another wise friend, said:

I think a good question to always ask yourself is *whose* approval you are seeking and how it serves you. I’ve been thinking about this as I’ve returned to school and have been working to let go of the desire for approval from my parents, understanding that as a practically impossible pursuit.

It feels good to be liked… and I think if that is your motive, just to be liked for the dopamine rush it provides, it can cause an issues once your self-worth can easily become interconnected with the external experience completely independent of you.

But the desire for approval from valued mentors, friends, partners, peers can serve us differently – it can help us build functional, healthy relationships where both parties are mutually invested in behaving in a way that results in approval or liking. It holds us accountable in a way, wanting to do right by a person. And I think we often grow by keeping expectations of each other reasonable. Working to feel validated, if consciously motivated, can help us do awesome things, I believe…

I find even knowing that people dislike me helps me self-reflect. It can again clarify values, sometimes discovering where you’re not willing to budge.

A lot of this resonates for me, because there are many elements of society that will never like or approve of me, because I am non-binary, I am bisexual, I am polyamorous, I am AFAB and often am read as femme. When I care what these people think of me (in the sense of wanting them to like or approve of me), I am caught in an impossible trap because the only way to gain that approval is to change who I am. However, even there I do care what they think because what they think points to systemic and structural injustices. I care what they think because I want to change the social context within which those thoughts of transantagonism, heterosexism, femmephobia, and all the rest (as well as all the injustices that I don’t face as a white settler with thin privilege, English language privilege, educational privilege, etc.)

Melanie also said, “I think we are too interconnected as a species and biosphere to be an island. We impact each other too much.”

I agree.

In yet another article, Tinybuddha suggests that, “Worrying about what other people think about you is a key indicator that you do not feel whole without the approval of others,” and, “When you are truly content with who you are, you stop being concerned with whether or not other people like you.”

The same types of questions come up.

Why does caring about the approval of others mean I don’t “feel whole”? Why can’t I “feel whole” while also caring about approval? Why is the approval of others automatically dismissed, when it is critical to having consensual and mutual relationships? What is active consent, other than enthusiastically and intentionally caring about getting the approval of the person you’re interacting with before taking an action?

This connects to Melanie’s points about whose approval we’re seeking, and to the idea of certain types of approval being entirely unavailable. Social isolation is recognized as a source of pain and distress, and social isolation is tied directly to what people think of us (whether we are likeable, friendable, loveable). And yet, the idea that we shouldn’t care what people think seems to greatly privilege individualism – being ourselves, being okay with being ourselves, even if that means being by ourselves.

My questions in writing this post kept coming back to why we valorize individualization. Why is it better to be an island? Why do we even believe we can be islands?! Isn’t there a whole song about how that doesn’t really work out? Sure, it may be true that the rock feels no pain, and the island never cries, and maybe that’s what we are hoping for when we distance ourselves from caring what others think. But that’s not the life that I want for myself.

Melissa Day points out that this valuing of individualization only happens within certain contexts. She writes:

[W]e fetishise individualism only within certain prescribed boundaries. Think of the hipster – I was into that before it was cool. Okay, great, you’re an individual. But someone who’s into completely different music/food/subjects and isn’t doing it to be “cool” or doesn’t have those become popular isn’t looked on as a heroic individual, but rather a weirdo or a freak (and yes, those words hurt and were chosen specifically). The sense I get is that there are two types of “don’t care what others think.” 1. They feel secure enough that who they are or what they like falls in society’s norms that they can be individual but still part of the whole 2. They like what they like and it falls so far outside society’s norms that caring about what others think really isn’t an option. This is written from the perspective of someone who had two choices growing up – change who you are and conform or stop caring about other people, be yourself, and take the lumps that followed.

…

I think… that it ties into this idea of everyone is special and unique. I would think the end goal of being different comes from a place of “If I am the same as everyone else, I will not be Special and Special is good.”

We are, collectively, put into a complex conundrum – we must care what other people think, and we must fit in, but we must do it in exactly the right way or we risk deviating too far from the norm and being punished for it.

As NoirLuna points out, “I feel like life would be way easier if blending in had been one of my options, but I figured out young it wasn’t, and managed to stop trying. (Which was for the good.)”

Wanting to Be Liked

Why is it a problem to care whether or not people like me?

I want my friends, my family, my lovers, my companions on this journey- I want them to like me!

I want them to like me because I know that I tend to spend time with people that I like. I am invested in relationships with people that I like. And I assume that other people are, if not exactly like me, then at least a little bit like me. So if my friends like me, they’ll want to spend time with me. They’ll want to be close to me. And I am invested in that outcome.

I have found that people are more likely to spend time with me when they like me.

And the reverse is also true. I have found that I don’t enjoy spending time with people that I don’t like, and I don’t enjoy spending time with people who don’t like me!

But then again…

There is a way of caring about what others think that can invite trouble. As Jonathan writes, “I’m out of balance over it. Caring what other’s think causes me anxiety. When I feel like someone is upset or angry with me I fixate on that. When I feel like someone thinks poorly of me or has a negative impression of my skill set it completely eats away at me. It makes conflict resolution very difficult for me to manage sometimes. It also means that I sometimes have a hard time being honest and authentic not only with the people around me but also with myself.”

Many folks can relate to that.

This topic has been challenging to write about because I, too, care “too much” about what other people think. I want people to like me. I want people to think that I am a good and worthy person. I want people to think that I am competent and capable.

The problem, as I have come to understand it in the process of sitting with this prompt, is not necessarily in caring what others think (I think I’ve been clear that I don’t consider that a problem!) but rather, when I create a totalizing narrative of myself based on what other people think. What I mean by that is, if I can only be “a good person” when everyone else agrees that I am so, that’s a problem. It’s a problem because no person is good all the time, no person can be.

Similarly, if I want to be a “worthy person” and I can only perceive myself to be that when everyone thinks I am, that’s a problem!

Ditto competency.

Ditto capableness.

The problem, in my mind, is when there is only room for a single story of the self. When that story is the one told by someone else’s opinion of us (including their opinion that we can only be “whole”, or “free”, or “authentic” when we don’t care what others think), it invites so much shame to the table. It invites us into so many feelings of personal failure. We need many stories of ourselves – stories of being good and stories of being less good, stories of being liked and stories of being less liked, stories of success and stories of growth. It is okay to care what other people think. It is okay to be conflicted about caring what other people think. It is okay to actively reject what other people think. There’s space. We need that space.

I struggled with this topic because, as much as I reject the idea that caring what other people think means I am somehow “not authentic” or “not whole” or “not free”, I have internalized the idea that I shouldn’t care what other people think. That it “isn’t any of my business” and that “the only thing I can control is myself.”

But this framing grates.

It feels wrong.

It feels far too individualizing.

Of course I care what people think of me! And so do the community members who consult me, and so does the patron who requested this topic, and so might you.

The idea that we should be fully autonomous, insulated individuals, small islands of personhood operating on our own, without caring or being moved by other people’s opinions… I think that’s a really harmful and hurtful idea.

That doesn’t mean that I am governed by other people’s thoughts, or that I am responsible for their thoughts, or that I am incomplete because I care about their thoughts. It means that, as Ken Gergen outlines, my reality (my worlds of meaning) is created through collaboration and context. When I engage meaningfully and intentionally with the people around me, including what they think of me and my actions, a lot of good in my life is made possible by this caring.

by Tiffany | Jun 6, 2018 | Business, Patreon rewards, preview/review, Writing, Zines

Friends! Where did May even go?! Wherever it went, it’s gone. Here we are in June! And here’s my review/preview post, which was posted for Patreon patrons on the first. It’s a miracle.

Okay, let’s start with May:

The new Patreon rewards have launched, and the first hand-drawn art cards have gone out! I’ve gotten really great feedback on them, and I had a lot of fun designing and drawing them. (If you’ve received your card and feel like sending me some feedback, I’d love to hear it!) The next batch of art cards will be going out in August to all patrons at $10 and up.

I’ve also created my first zine! It’s a tarot-themed zine, not in line with most of what I post here, but I’m really happy with it. I sold it at my first-ever “reading tarot at a fair” event. I think I was the only tarot reader there who wasn’t doing any kind of mediumship or divination – not telling the future, just using the cards to invite the person in front of me to think about their narrative in new ways. I am actually really interested in how tarot and narrative work can work together – I find the metaphors and symbolism in tarot so rich and inviting. Even though I was reading tarot differently than most folks, it worked for me and I got some good feedback, and it’s the only way I can feel ethical about using this tool. And it was a lot of fun! If you’re interested in that zine, it’s available for $5 in either digital or physical form. Send me an email and I’ll send you the zine!

The next zines will be more clearly in line with my narrative work – check the bottom of this post for the call for contribution links! These zines are both open to contributors, and will also feature my original content. All of the zines I’m creating (I am aiming monthly-ish) are sent out to anyone who supports my Patreon at $20 and up, and they will also be available for sale on my website.

My first blog post for the Association of Alberta Sexual Assault Services went up. You can read it here! It’s about how to support your partner if they have experienced sexual violence.

In the Masters program, I got a ton of work done. There were five assignments due in May:

– A 15-minute segment from a narrative therapy session

– Transcription of that segment

– A 1000-word analysis of the segment (these three not posted for reasons of confidentiality)

– A 1000-word reflection paper on the topic of re-membering conversations (posted for $5 and up patrons here)

– A 1000-word reflection paper on the topic of ethics and partnerships (posted for $5 and up patrons here)

The May Possibilities meeting was fantastic. We talked about media representation, and I’ll have the shareable resource completed and posted next week.

I did not get any blog posts written, but I did get the Feminism from the Margins May contribution up, and that was quite a bit more effort than usual since Mel Vee wrote four pieces rather than one. Those pieces of writing are powerful and deeply personal reflections on living as a queer Black woman. You can read them here, here, here, and here.

I did make progress on the Possibilities Youth project. I had two meetings with folks to talk about the logistics of running a youth group, and I have a space booked for a six-week pilot group. I’ll be announcing more details within the next month.

And I facilitated a lunch-and-learn at Chevron on the topic of “Pride 101: LGBTQIA2S+ Terminology” (the handout for that has been posted for $5 and up patrons here), and the feedback was fantastic! (One person wrote, “Thank you so much for organizing this incredibly interesting and very meaningful event. Tiffany was amazing! I learned a great deal and plan to work hard at being a good ally.”)

Sadly, I did not get the grant that I applied for. I’m going to keep trying, though. I just need to find some other ones to apply for!

And now, what’s coming up in June:

The first, and most exciting/terrifying thing for me, is that I’m finally taking this “figure out the marketing” thing seriously. I’m going to get the shop set up on this site, update my page to reflect all of the new services I’m offering, and revise my social media strategy. This won’t happen quickly, but it’s ramping up.

Figuring out my marketing honestly should have been at the top of my priority list a long time ago, but sometimes we don’t make progress until we’re forced to, and that’s okay. It’s not like I’ve been slacking, I just haven’t been focusing on marketing (because marketing is not a natural fit for me, and gives me the Bad Capitalism Feels).

What does that mean for what’s coming up?

I’m going to be posting more often on the Facebook page, here my blog, and on the Patreon (mostly cross-posting, but I’m curious about whether folks have a preference in that regard!). Since I’m going to be posting more often, I’m going to start writing my posts in advance, sharing them on the Patreon early, and then posting them on the blog and the Facebook page. I’m working on getting a little stash of posts written so that I can get that ball rolling. I’m hopeful that this will build interest in the Patreon, and also allow me to engage with my social media audience more effectively.

I’m also going to figure out how to actually be present on Instagram in a more meaningful and effective fashion. And on LinkedIn. And maybe Medium? This is literally me:

Image description: A five panel comic. In the first panel, a person with a beard says, “keep going! you’re almost there!” In the second, a person with a ponytail is running towards a ball labeled “goal”. In the third, the ponytailed person is still running towards the goal and, a shiny golden ball labelled “new goal!” rolls past. In the fourth, the ponytailed person looks after the shiny new goal. In the fifth, the ponytailed person is running after the new goal, and the bearded person says off-screen, “noo, finish the other one first!” This comic is by Catana Comics, and they are so cute!!

And I’m going to figure out this networking thing. I have a coffee date in June with the person who brought me in at Chevron, and she’s going to give me some advice on networking into more lunch-and-learn opportunities.

I’ve also sent a message to a friend of a friend, who has reached out to a few of her connections in HR positions, to see about bringing me in for lunch-and-learns. I still need to figure out how to start networking into more narrative therapy work, but… I’ll get there.

The two blog posts I had hoped to write in May, I will be writing in June. So you can look forward to a post on Self-Care and Caring What Other People Think About Us, and an interview post about major life transitions. I’m also going to be writing a post on re-membering conversations, similar to the post about connecting to our skills that I wrote in April. I’m aiming for once-a-month-ish “intro to a narrative practice” posts.

I’ll be recording and sharing a short series of videos answering questions about narrative therapy. If you want to submit a question, send it to me this week! I’m working on this video series now, and am using it as an opportunity to learn some editing skillz.

The questions I have so far are:

– How do I explain narrative therapy to someone?

– Is it counselling or writing your life story?

– Why would I pick narrative over cognitive behavioural therapy?

– How do I know if narrative therapy is right for me?

– What are the risks, if any, of narrative therapy?

– Isn’t it just pretending that things are different? Isn’t that just avoidance or delusion?

– Do I need to be a writer / creative type person to benefit from narrative therapy?

– How would someone with dissociative tendencies be able to use narrative therapy around periods of time when they weren’t present?

– Can I use narrative therapy to get dates? (This was submitted as a joke, but I’m legit considering answering it because we could certainly talk about what it is you are valuing in the desire to “get dates” and what your previous experiences has been in this regard, and why you are looking for therapeutic help in this way. It’ll be a funny but informative answer, is what I’m hoping.)

Do you have questions about narrative therapy? Send them to me, and I’ll answer them in a video!

I have two assignments due in the Masters program, both 1000-word reflections that I’ll post on the Patreon after they’re written. (Update since this was posted – the first of these is up! If you want to read my Masters program papers, you can get access to those exciting pieces of work for just $5/month.)

And! Very exciting news! Back in April, Cheryl White (one of the directors and founders of the Dulwich Centre) sent me an article that was going to be published and asked for my thoughts. I sent her my thoughts, including some critique. She appreciated the critique and….

*pause for dramatic effect*

… the Dulwich Centre is sending me and another narrative practitioner to Sacramento on a two-day trip to meet the author of the article, David Nylund, and tour the Gender Health Centre and do some narrative sessions with the therapists there, so that I can then share my learning with the Dulwich Centre and help support their increased trans-inclusivity and awareness, and also co-author a paper that will be included in next year’s course readings.

Okay.

Let’s just pause for a second before freaking out about this, and then freak out about this, because this is amazing. This is exactly what I want to do with my life – travel, meet and interview people, create content that will increase justice and decrease marginalization in the world. This is what I want for my life! (Just imagine if this Patreon grew and I could do this kind of work with crowdfunding. *wistful sigh*)

Anyway.

Because May was so challenging in my personal life, I am going to head down to Sacramento a few days early and take a few days to write, read, and recover.

I will definitely post the paper that I write, and any other documents generated as a result of this trip, on the Patreon and probably also on the blog.

*muffled squealing*

I am pretty excited.

And, I’ve also got a couple events coming up in June:

On Sunday, the Self-Care Salon will be running, this month with a focus on Justice and Access to Support. I am very excited about this discussion and the resulting collective document. (Update: This event was fantastic and I will be generating the collective document following the conversation within the next couple weeks.)

On June 19, Possibilities will be talking about Queerness and Parental Relationships (both relationships with our parents, and as parents ourselves).

Now, the zines! (You can also find all of the open calls for contributions in a new album on the Facebook page.)

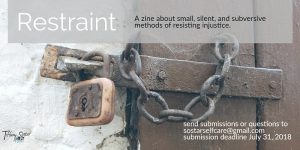

Image description: A rusty lock and chain on a wooden door. Text reads “Restraint: A zine about small, silent, and subversive methods of responding to injustice. Send submissions or questions to sostarselfcare@gmail.com. Submission deadline July 31, 2018.”

Restraint –

1. a measure or condition that keeps someone or something under control or within limits.

2. self-control.

How do we experience restraint?

How do we resist injustice?

How do we break free, break open, break stigma, break barriers?

How do we speak?

Many of us are resisting injustice from a place of external or internal restraint. Either being controlled or controlling ourselves, or both.

We may not “come out” because it wouldn’t be safe, or because it isn’t the way we want to move through our world, or because it would jeopardize our relationships or our work.

We may not “speak up” to bullying, abuse, or injustice because it would put our career in danger, or it would put people we love in harm’s way, or because other people have power over us and we can’t afford to antagonize them, or because we have other ways of resisting those injustices.

(Disabled folks who can’t speak up to injustices committed by their carers because of the power differential, racialized folks who can’t speak up to injustices in the office because they’ll be labelled “angry”, trans folks who can’t speak up to injustices in the medical community because it would put their access to transition support in jeopardy – there are so many of these situations!)

But despite these restraints, people are never passive recipients of trauma or injustice. As David Denborough says in the Charter of Storytelling Rights, “Everyone has the right for their responses to trauma to be acknowledged. No one is a passive recipient of trauma. People always respond. People always protest injustice.” (https://dulwichcentre.com.au/narrative-justice-and-human-rights/)

There are many ways to resist, challenge, and respond to injustice.

This zine celebrates and recognizes the small, silent, and subversive responses to injustice.

It is inspired by the April Possibilities bi+ community discussion of “the closet”, and by the March Self-Care Salon discussion about being a professional on the margins, as well as other conversations and experiences of restraint (both restraint that is painful and externally imposed, and restraint that is joyful and internally chosen).

Do you have a story of restraint?

Send your submissions of art, comics, short fiction, non-fiction, poetry, or essay to sostarselfcare@gmail.com before July 31, 2018. You can also send your questions.

(Depending on the number, size, and content of submissions, some may be edited. Nothing will be put into the final zine altered without the author’s consent.)

AND!

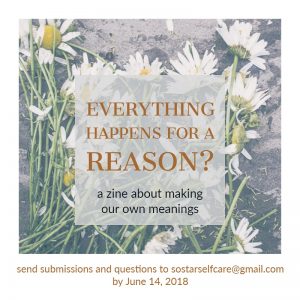

Image description: Cut daisies are scattered on pavement. Text reads, “Everything happens for a reason? a zine about making our own meanings. send submissions and questions to sostarselfcare@gmail.com by June 14, 2018”

“Everything happens for a reason.”

“The universe must have a lesson for you.”

As a response to grief, to loss, to pain, to injustice, these phrases that are meant to be comforting can end up being incredibly hurtful.

Although people do always respond to the traumas, injustices, and hardships in their lives, and these responses often leave us with valuable skills and insider knowledges, the idea that we experience trauma, injustice, and hardship because we’re meant to, or because it’s “good for us”, or we have somehow attracted it, or we need to experience it, is often a bitter pill to swallow.

So spit that pill out!

Let’s write, draw, poem, collage, photograph, paint, and talk about the meaning we make from our hard times (the lessons we learn, skills we develop, knowledges we gain), and the nonsense of our hard times (the *lack* of lesson, the pain that we just feel and do not ever appreciate), and let’s resist the idea that these hard times are somehow necessary, or “good for us.”

Send your submissions to sostarselfcare@gmail.com by June 14, 2018!

And if you have thoughts but aren’t comfortable writing them out, let me know and we can do an interview!

My big collective document projects – extroversion, self-care for queer geeks, financial self-care on the margins, and bad gender feels project, as well as my on-the-to-do-list smaller documents – self-care and the closet, the write-up of the first professionals on the margins meeting, are all in limbo. I hope I’ll have time to get to them in June, but I’m trying to keep my goals reasonable. They will happen eventually, but I’m not entirely sure when!

I really need to book more narrative therapy clients, too. So, if you know anyone, or if you’re interested in working with me, let me know!

Anyway! That’s the review/preview!

Thank you so much to each of my patrons and supporters. The vast majority of what I do is not funded and I don’t charge for the work, and without your support, I don’t know if I could keep going. You make this work possible. <3

by Tiffany | Feb 8, 2018 | Health, Identity, Intersectionality, Narrative shift, Neurodivergence, Patreon rewards, Personal, Step-parenting

Image description: Kate’s incredibly stylish orange cane, leaning against white drawers with silver handles, on a wooden floor.

This is a Patreon reward post for Kate, and was available to patrons last week. Patreon supporters at the $10/month level get a self-care post on the topic of their choice during their birthday month. These supporters make my work possible! Especially as I head into my Master of Narrative Therapy and Community Work program, my patrons ensure that I can keep producing resources and self-care content. (And wow, there are some really great resources in production! Check back tomorrow for a post about that!)

Kate and I have known each other for a few years, and got to know each other while we were both going through some challenging times (though we didn’t actually meet in person until quite a bit later, and still aren’t able to spend as much time together as either of us might like!)

Kate has been one of my most outspoken supporters, and I appreciate how she is always willing to leap in with an offer of help or a suggested solution.

Her birthday is in January, and her topic is, “maintaining intimate relationships and partnerships with a chronic illness or chronic pain.”

I struggled with writing this post because I am experiencing my own spoon shortage. I’m in the middle of a depressive episode, have been sick for the last two months, and my fibromyalgia pain has been spiking. All of these spoon-hoarding gremlins are impacting my own relationships, challenging my sense of who I am and how I navigate the world, and putting gloom-coloured glasses on my view of the future. When I write about self-care for folks who are struggling, it’s easier when I can write about a struggle I am not currently experiencing. It’s easier if I can yell back into the labyrinth from the safety of the outside. Easier, but not always better. It is a myth that the best insights come from people who have “figured it all out” – I believe the opposite is often true. When we are in the thick of it is when we have the most relevant and meaningful insider information. Our struggle is not a barrier to our ability to help each other – it is the fuel that allows us to help each other. This is one of the key principles of narrative therapy, and as much as it challenges me, I am trying to bring it into my own life. Can I write something worthwhile from the heart of the struggle? Yes. Well, I think so. Let’s find out.

What Kate asked about was maintaining intimate relationships while navigating chronic illness or pain. In relationships where one person experiences chronic issues and another doesn’t, those issues can create a significant disparity in ability and access to internal resources. (And in relationships where multiple people are experiencing chronic issues, the pressure resulting from reduced access to resources can grow exponentially.)

Being in the position of having (or perceiving that we have) less to offer often triggers shame, fear, and stress. In my own relationships, I worry that I’m not worth it, that my partners will grow tired of me. I worry that I’m “too much.” I have heard the same worry from my clients.

This anxiety is so natural, and so understandable. Our society does not have readily accessible narratives that include robust “economies of care.” Our most common narrative has to do with “pulling our own weight” in a relationship, and our definitions of balanced relationships rely so heavily on ideas of equality rather than justice. Split the bills 50/50. Take turns washing the dishes. You cook, I’ll clean. My turn/your turn for the laundry, the diapers, the groceries.

And it becomes more complicated when we consider the intangible labour of emotional support and caregiving, which is disproportionately assumed to be the role of women in relationships with men, and, since women are also often the ones experiencing chronic pain or illness, this can compound into a messy and unjust situation pretty quickly. (To back up these claims, check out the links at the end of this post.)

Thankfully, both of these problems – the tit-for-tat approach, and the unjust division of emotional labour – are being challenged by writers, activists, and communities on the margins.

In Three Thoughts on Emotional Labour, Clementine Morrigan writes, “We can name, acknowledge, honour, perform, and yes, accept emotional labour, instead of simply backing away from it because we don’t want to be exploitative.”

This is so challenging for so many of us, because we do not want to exploit our friends, our partners, our communities. When we experience chronic illness or pain, the fear that we might slide into exploitation and “being a burden” becomes amplified. Morrigan suggests that we can ask three guiding questions about the emotional labour we are offering or accepting – Is it consensual? Is it valued? Is it reciprocated?

If we can answer yes to each – if we are discussing what we need and what we can offer, if we are valuing what we are offered and if our own offerings are valued, and if there is reciprocity – fantastic!

But what does reciprocity look like in situations where there is a disparity in access to resources?

Morrigan suggests that:

“It is important to acknowledge that some of us need more care than others. Some of us, due to trauma, disability, mental health stuff, poverty, or other reasons, may not be in a position to provide as much emotional labour as we need to receive. We may go through periods where are able to provide more emotional labour or we may always need more care than we are able to give. We may be able to reciprocate care in some ways and not others. This is totally okay. We need rich networks of emotional care, so that all of us can get the care we need without being depleted. We need communities that value and perform emotional labour—communities that come through for each other. Reciprocity is a commitment to building communities where all of us are cared for and no one is left behind; it is not a one for one exchange.”

It is not a one for one exchange.

This is so critical.

And it’s so hard to make space for this. It’s hard to see our worthiness and the value we bring to a relationship when what we offer has shifted from what we were able to offer before the chronic issue grew up within us and between us.

Not only that, but it’s often hard for our partners to recognize what we’re bringing to the relationship. Not because they don’t love and appreciate and support us, but because they are also caught within the web of accessible narratives and ableist norms.

In order to answer “yes” to Morrigan’s “is it valued?” question, we need to be able to look clearly at the work our partners, friends, and families are doing for us and acknowledge that work. And we need to be able to look clearly at our own work and speak openly about it, so that it can be valued. Neither side of this is easy.

Becoming aware of the skills and insider knowledges that we develop as we live our new pain-, disability-, or illness-enhanced lives can help with recognizing, articulating, and allowing people to value our new contributions.

In A Modest Proposal For A Fair Trade Emotional Labor Economy (Centered By Disabled, Femme of Color, Working Class/Poor Genius), Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha writes:

“Sick and disabled folks have many superpowers: one of them is that we often have highly developed skills around care. Many of us have received shitty, condescending, charity-based care or abusive or coercive care—whether it’s from medical staff or our friends and families. We’re also offered unsolicited medical advice every day of our lives, mostly coming from a place of discomfort with disability and wanting to “fix” us.

All of this has made us very sophisticated at negotiating care, including our understanding that both offering and receiving it is a choice. The idea of consent in care is a radical notion stemming from disabled community wisdom. Ableism mandates that disabled people are supposed to gratefully accept any care offered to “fix” us. It’s mind blowing for many people to run into the common concept in many sick and disabled communities, that disabled people get to decide for ourselves the kind of care we want and need, and say no to the rest. This choicefulness has juicy implications for everyone, including the abled.”

I love her wording here. The juicy implications of choicefulness! Imagine the possibilities of this.

And yet, even as I revel in this juicy and nourishing framework, I remember my own deep and ongoing struggle with the concept of pain, illness, and disability as invitation, as superpower, as self. This radical reorganization of labour within relationships does not come easily, and one of the reasons it’s so challenging is because our concepts of fairness are so influenced by one to one exchanges.

Piepzna-Samarasinha addresses this fear later in the essay, reminding us that, “Disabled people often run into the idea that we can never offer care, just receive it. However, we often talk about the idea that we can still offer care from what our bodies can do. If my disabled body can’t lift yours onto the toilet, it doesn’t mean I can’t care for you—it means I contribute from what my particular body can do. Maybe instead of doing physical care, I can research a medical provider, buy groceries for you, or listen to you vent when one of your dates was ableist.”

We forget that there is still care, still reciprocity available within our relationships even when our ability to perform the tasks we used to, or the tasks we wish we could, has shifted.

Learning how to navigate this shift is challenging.

Searching for resources to share in this post, I was discouraged by the sheer volume of academic research performed by normatively abled “experts” on the outcomes for relationships that include a disabled partner. Once again, the centre scrutinizing the margins. It creates such a disempowering framework.

I was also dismayed by the fact that “should I date a disabled person” was one of the suggested related searches. Gross! GROSS!!!!

These are the narratives, and the social framework, within which we try to navigate our relationships as pain/illness/disability-enhanced individuals.

We need more robust, inclusive, intersectional, and hopeful resources. Not hopeful in the “look on the bright side” gaslighting-via-silver-lining sense. Hopeful in the sense of possibility-generating, hope that, in Sara Ahmed’s words, “animates a struggle.” Hope that reminds us that there are narratives possible outside of the ableist norm, and that we can write those love stories within our own lives.

The parts of ourselves that do not fit tidily into the ableist ideal show up in our relationships in many ways. In order to write those inclusive love stories of any kind – platonic, romantic, familial, or parental – we need to recognize and learn to navigate all of it. Financial, social, emotional, physical, mental – very aspect of ourselves that requires tending and care.

Chronic illness/pain/disability impacts our financial lives – we are often less able to work within normative capitalist models. The 8-5 grind doesn’t work if you can’t manage a desk job for 9 hours a day, and many other jobs are also out of reach. This adds pressure to our partners and social supports. Money is a huge source of shame and fear for many of us, so learning how to talk about requiring financial support, how to shift the balance of contribution in a household – overwhelming! Be gentle with yourselves in these conversations.

I find this particularly challenging. More than almost any other way in which my chronic issues impact my relationships, the financial instability that has been introduced as a result of my no longer being able to work a full-time job feels humiliating and shameful. I am working hard to carve out a living for myself, to build my business in sustainable and anti-ableist ways, to do what has to be done to pay my share of the bills. But my partners still take up more than what feels “fair” in the financial realm, and it’s hard. For me, engaging with writers, activists, and advocates who are challenging capitalism and neoliberalism has been helpful. Recognizing that there are other economic models available has opened up some space for me to still see myself as a contributing member of my partnerships and society.

Chronic illness/pain/disability also impacts our social lives – getting out to see friends can become more challenging. Our partners can end up taking on more social caring work for us, being the ones we talk to when we aren’t getting out (or when we don’t feel safe to talk about our struggle with others).

The aggressive individualism of our current anglo-european culture means that we are often isolated, and this can be so discouraging. Again, I struggle with this personally and I don’t have easy answers.

And searching for resources on parenting with chronic pain, illness, or disability is similarly challenging and disheartening. Parenting with any kind of divergence from the ideal is difficult. The weight of judgement, assumption, erasure, hostility, and isolation is so real. Although more supportive and inclusive blog posts, research papers, and articles are being written, the perception of a weirdly-abled parent is still one of lack, inability, and pity.

We often want to provide everything our children needs, without outside help. That’s the expected ideal. The nuclear family is still the celebrated norm, and the ideal of a normatively abled, neurotypical, stay-at-home, biological parent is still the target to meet. We may recognize that “it takes a village” but we resist the idea that part of what that village offers may be physically chasing after the toddler, lifting the baby, doing homework with the teen, helping with the rent. Just like we need to expand our conception of emotional labour and economies of care within relationships, we need that same expansiveness and redefinition within our parenting relationships and roles.

Which is easy to say, and incredibly hard to do.

At Disability and Representation, Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg writes, “What so many able-bodied feminists don’t get is how profound an experience disability is. I’m not just talking about a profound physical experience. I’m talking about a profound social and political experience. I venture out and I feel like I’m in a separate world, divided from “normal” people by a thin but unmistakeable membrane. In my very friendly and diverse city, I look out and see people of different races and ethnicities walking together on the sidewalk, or shopping, or having lunch. But when I see disabled people, they are usually walking or rolling alone. And if they’re not alone, they’re with a support person or a family member. I rarely see wheelchair users chatting it up with people who walk on two legs. I rarely see cognitively or intellectually disabled people integrated into social settings with nondisabled people. I’m painfully aware of how many people are fine with me as long as I can keep up with their able-bodied standards, and much less fine with me when I actually need something.

So many of you really have no idea of how rampant the discrimination is. You have no idea that disabled women are routinely denied fertility treatments and can besterilized without their consent. You have no idea that disabled people are at very high risk of losing custody of their children. You have no idea that women with disabilities experience a much higher rate of domestic violence than nondisabled women or that the assault rate for adults with developmental disabilities is 4 to 10 times higher than for people without developmental disabilities. You have no idea that over 25% of people with disabilities live in poverty.”

So that fear of embracing a new normal, subverting the neoliberal individualist norm, creating new economies of care and radically altering our relationships to be just rather than equal… this doesn’t happen in a vacuum. We aren’t just subverting norms and creating new relationship methods – we are doing so, as parents, under the scrutiny of an ableist and highly punitive culture. We are conscious of the fact that our subversion of norms, which may be possible within adult relationships, may make our parenting relationships more precarious, more tenuous.

Access to external help is readily available to the professional upper class – nannies are a completely acceptable form of external help, and parents are not judged for needing a nanny when that need is created by long working hours. Needing help in order to be more productive? Sure thing. (You’ll still face judgement, of course. Can any parent do it “right,” really? Nope.)

But needing help because of pain, illness, or disability?

Yikes.

That is much less socially sanctioned, and there are far fewer narratives available that leave space for that choice to be aligned with a “good parent” identity.

And yet, many of us do parent while in pain, while ill, while disabled. And we are good parents. Just like we have valuable superpowers of caring that can be brought into our adult relationships, we have the same superpowers of caring to bring into our parenting roles. What we do may look different than the pop culture ideal. How we do it, when we do it, who helps us with it – that might all look different. And that’s scary. But the value it brings to our kids is immeasurable.

One of the invitations that chronic illness, pain, and disability extends is that it pulls the curtain back on how harmful the neoliberal ideology of rugged individualism really is, and asks, “is there another way?”

I’m not great at saying “yes” to that invitation, but I’m getting better at recognizing it when it shows up. I don’t need to have all the answers, because I have a community around me that is brilliant and incredibly generous.

So, when I was struggling with this post, I asked my best friend and one of my partners to help me.

H.P. Longstocking has been dealing with the long-term effects of two significant concussions, and in a moment of discouragement at my own inability to write this post, I asked if she could help me get started. What she sent touched on so much of what I wanted to write about, so eloquently, and I’m ending this post with her incredibly valuable contribution. She is a parent, a scholar, and an integral part of the social net that keeps me going. I think there’s hope in how she has responded to this.

She writes:

While I am no stranger to depression or anxiety, I had never experienced a chronic debilitating illness and I found that my self-care habits and techniques were no longer usually helpful or even always possible. Last summer I had several concussions. Because I had sustained so many as a child, these two accidents completely changed my life. Most of the summer I was not safe to drive or even walk as my second concussion happened when I tried to walk out of my bedroom and due to the concussion symptoms, I cracked my head into a wall. I could not look at screens, read, handle light or loud noises, and was told to stop having sex. All of my self-care habits were taken away.

I have always been an active person. Running and cycling have been my times of meditation and recalibration. Dancing brings me joy. Physical activity has been an integral part of my self-care since I was a small child. To have days, weeks, and months where walking short distances is the most physical activity I can safely manage, and some days not even that, has had a detrimental impact on my body and my emotional well-being.

I used to love to read. I devoured books and articles. I had just started my Masters and was supposed to be immersing myself in the scientific literature. I could not do any of that. I still struggle. Reading was my escape, my lifeline, my lifeblood, and I hoped, my livelihood. Now it causes me pain.

I was not prepared for the constant, chronic pain. Previously, I had headaches so rarely, I did not recognize them the few times a year I would experience one. Now, I have a hard time recognizing it because I am never without one. I find that I have my face screwed up in pain after someone reacts to me as if I am scowling at them. My coping mechanisms for the pain are to hyperfocus on something so I am unaware of most of the world around me. Unfortunately, this is usually my phone which in the long term makes it worse, but also as it gets worse, I have less self-control and ability to stop myself.

All of this has impacted my relationships. Without the ability to drive, I am often limited in who I can see and where I can go. Even without that, I am easily tired in social settings and my words begin to slur in mental exhaustion. I cannot handle loud spaces for very long, or if I do, I pay for it with days of recovery. I often feel isolated, alone, and incapable of taking care of myself, let alone being the partner, parent, and student I aspire to be.

But, I have adapted. Instead of reading, I listen to audiobooks. Instead of digesting dense theory or the latest studies, I listen to light narratives and fiction that has a plot so predicable that I can fall asleep and not miss much. I go for short walks instead of long bike rides.

My relationships have also changed.

It is hard to feel like you are not carrying your weight, especially in this neoliberal culture where people are valued according to how much productive and profitable output they can do. It is hard to be a partner with someone when you are more dependent and roommate than lover. It is hard not be able to see people, leave the house, focus on what someone is saying, or do what they are doing. It is so isolating and would be so much more so with poverty added as well. It hurts to see your kids do an impression of you which is just sleeping.

My friendships have changed. I am slowly learning to ask for help. To say no. To cancel plans last minute because it is not safe that day for me to go out. I cancel plans so often now that I am scared to make them. Much of my socialization now is online and sporadic. There is a price to pay for too much screen time. I am spending more time with people I do not have to hide my pain from. I do not have the resources to put up with mind games and people who suck energy. I have a few friends that make safe spaces for me to come and just nap around them so I won’t feel alone. My life is rich, even though my world and abilities have shrunk.

Self-care looks entirely different to me now. Instead of the sun on my face and the pounding of my feet on running paths, I sip tea wearing sunglasses. Instead of pushing through discomfort, I am learning to listen to it so that I do not make things worse. Instead of losing myself in the written word, I find comfort in story, sound and other sensory delights. Some of the people I spend time with have changed, and the ways I spend time with people have also. I do not know which symptoms will resolve and which I will have for the rest of my life, but while I grieve for friendships and opportunities lost, I am also grateful for the capacity to change and adapt, and trust that relationships worth holding onto can withstand the changes as well.

Further reading on emotional labour:

- Wondering about women’s differential experiences of pain? Check out the trans-inclusive Popaganda podcast on Women and Pain.

- And this Everyday Feminism article on how emotional labour defines women’s lives will give you insight into women’s experiences of differential expectations of emotional labour.

- And, if you want to challenge the gender disparity regarding emotional labour in straight relationships, check out 7 Ways Men Must Learn to Do Emotional Labour in Their Relationships.

- It’s also important to bring an intersectional lens to any discussion of emotional labour, and this article on Emotional Labor, Gender, and the Erasure of Autistic Women is both an excellent article on its own, and full of worthwhile links out.

- The Emotional Labour of the Closet: A Look at Trans Women’s Socialisation touches on the specific emotional labour that trans women are expected to offer.

- And we can’t discuss differential expectations of emotional labour without acknowledging misogynoir and the demands on Black women to be caregivers for their own communities and the white communities around them. Misogynoir and Black Women’s Unpaid Emotional Labour touches on this issue.

- And then, tie it back to chronic illness, chronic pain, disability. Disability and Emotional Labour talks about these issues, and although it’s an article related specifically to activism, it comes into our lives and relationships in many ways.

by Tiffany | Jan 6, 2018 | Grief, Patreon rewards

Image description: A bare tree in silhouette against a dark blue and black sky. Image credit: Gerd Altmann (pixabay).

This post was first shared in Version 1 of the Holiday Self-Care Resource. This expanded version is a Patreon reward post for Samantha, who is one of my most enthusiastic supporters and a close friend.

Samantha lost her father, and asked me to write about “the intersection of the Holidays and Loss. The expectation to participate versus honouring grief.”

This topic is so deep, and so difficult, and so important.

We all experience grief and loss at some point in our lives, and we all navigate holiday expectations and experiences following the loss. Although we each feel the loss individually and uniquely, the fact that we will feel loss is universal.

It’s painful.

It’s terrifying.

Our culture is not particularly death-affirming. And by “not particularly,” I mean “not at all.” We prefer not to think about death, not to talk about death, not to know about death. I count myself among that majority, and am deeply uncomfortable with the idea of mortality – my own, and that of my loved ones.

When Samantha notes the conflict between participation in holiday traditions and honouring grief, she is highlighting a critical gap in how many of us navigate death and loss. Death is not welcome at the holiday table. Our grief – the full raw intensity of it – is not welcome. We remember our lost community members briefly, and with restraint. We do not wail. We do not sink to the floor in despair. It’s Christmas, for fox sake! We are often encouraged to “think positive,” to remember the good, to focus on the silver linings, and to have faith that time will heal even the deepest wounds. These dismissals of our full grief can be felt as dismissal, erasure, invalidation. They can trigger shame, fear, anger, and loneliness. Are we grieving wrong? Are we wrong to grieve?

This conflict between connection with the living and connection with the dead, and this distancing from connection with our own deeply grieving selves – it hurts. It contributes to the pressure and pain that often accompany the holiday seasons.

And, I suspect it is unnecessary.

If we were able to make our way towards more death-affirming, death-accepting, and emotionally whole holiday traditions, then it would be possible both to participate and to honour our grief. But since we are not there yet, we are left with the same problem that dogs all of self-care – the best solution is collective and not individualized, but the available solution is often a solo venture.

So, how do we honour our grief in the holiday seasons?

How do we navigate the escalating intensity of our grief at just the time when our friends become busier and less available, and our cultural scripts become more constricted?

This becomes even more complex for people who are experiencing grief’s cyclical nature – one year we are okay, the next, or two years later, or five, or ten, the tide comes back in. Grief is often given an expiry date in our culture, and if we cycle back into the depths of it during the holidays, after that expiry date has passed, it can be hard to find space or acceptance for our feelings.

“Time heals all wounds” is an aphorism that comes with a subtext. If time has passed and you are still wounded, what are you doing wrong? Are you picking at the scab? Are you obsessing? Have you failed to “let go”?

This idea of “letting go” is one of our central grief narratives, and it can be intensely hurtful. We often fear letting go because we fear losing the person from our lives entirely. We are supposed to move on. But we often fear moving on, because it feels like a betrayal. And that’s okay. “Letting go” is not the only way to navigate grief.

Other cultural narratives are equally painful. “A big grief is a big love” may be true in many cases, but it puts anyone who has lost someone into a tricky double bind. Grieve big enough to demonstrate your love, but also grieve quietly enough to keep people around you comfortable, and quickly enough to be over it within an acceptable timeframe. Big, but not too big. Visible, but not too visible. Loud, but not too loud. Mention it, but mention it at the right time, in the right way. And then don’t mention it too often after that.

And when it comes to mentioning it, “don’t speak ill of the dead.”

For those of us who are queer or trans or neurodivergent or fat or otherwise non-conforming, whose families may have rejected us or struggled to accept us, how do we speak about the people we’ve lost? People we may have loved deeply, but who may also have wounded us deeply? The fragmentation at the core of so many of our narratives about grief becomes visible here, too.

These narratives contain some truth.

It can be a valuable part of the healing process to “let go” – to honour the transition of our loved one from living to dead, to hold space for that shift, to acknowledge that change.

It can be true that big love leads to big grief, though I challenge the idea that the two are always exactly correlated.

It is true that time heals many wounds, when paired with other healing elements.

And I think that there is value in being intentional about what stories we bring forward about our dead, though I disagree that the rule should be to only share the good. People are light and shadow, high and low. We each live in the grey spaces, and I don’t see how it truly honours our dead to pretend they were perfect. We lose their humanity when we sanctify them in death, I think.

And there are other pressures, other narratives, other assumptions that cause that intersection of the holidays and grief to be so challenging.

How do we grieve our best friend when faced with “just a pet” narratives?

How do we grieve our queer lover who wasn’t out? Or if we aren’t out?

How do we grieve our trans community members when they are being misgendered, when our acknowledgement of their gender is not welcome in the grieving space?

How do we grieve losses in families we have divorced out of?

How do we grieve miscarriages, abortions, and other pregnancy and infant losses that are less socially acceptable? (There is an incredible, queer and gender-inclusive, community-built resource on this topic, available here.)

How do we grieve estranged family?

How do we grieve our abusers, when we still loved them? The idea that we can just cut them out is often good advice, and sometimes possible. But what happens to the grief of those of us who didn’t, or couldn’t, or didn’t want to? What happens to our grief when we havecut them out, and then they die? Are we allowed to grieve then? How? With whom?

How do we grieve a break-up, a divorce, or a loss of friendship?

All of these disenfranchised griefs – grief that is not socially acceptable and therefore hard to express, and hard to find support for – are so overwhelming and isolating. Always. But even more at the holidays.

What is the alternative to these pressures, disenfranchisements, and hurtful narratives that ramp up so intensely at the holidays?

One alternative is to retreat with your grief. If you know that your grief will not be welcomed in certain holiday activities, it is okay to skip them and to be with your grief and with whatever people can come into that with you.

There are costs to this. Especially if a grieving family is split in how to handle the holidays following the loss, or if some members of the family are in a quiet part of the grief cycle and others are in a storm, there can be resentment. If some family members want to come together as a family to find solace and joy, and others want to have quiet and solitude to reflect and process – that’s a recipe for conflict and for feelings of resentment and hurt on both sides.

There aren’t any easy answers.

Communication helps, but communication is hard when we’re grieving. Grief makes everything hard.

Self-awareness helps. Letting yourself see what is happening, holding space for your own grief, knowing that your irritability, your sensitivity, your lack of patience, your lack of appetite – they are all normal, and they are all part of the grieving process. But self-awareness is also hard. Knowing the depth of our grief can be overwhelming. Especiallyif we are past the socially sanctioned expiry date on deep grief.

Compassion helps, both for ourselves and for our communities. But, again, compassion is hard! Self-compassion requires allowing ourselves to be struggling, allowing ourselves to be low, to be sad, to be weak. At a time when we are already more conscious of our mortality than otherwise, more aware of the fragility of our own and everyone else’s lives, this is such a huge ask. And compassion for our communities is also incredibly difficult at these times, when someone else’s form of grief may feel like an affront or an invalidation.

For ourselves, honouring grief might mean journaling about our relationship with the lost person, making art, sitting quietly with our memories, speaking about the relationship, allowing ourselves to cry.

For complicated grief, we may need to speak about the good and the bad, and have a safe and welcoming space for those hard conversations, with someone who won’t shame us for speaking about the bad, for still loving the good, or for grieving.

Equally important, the person we trust with these stories will need to not reject or dismiss the good qualities just because of the bad. Coming into that space requires a willingness to be compassionate and non-judgmental. It’s one of the most loving things we can do for a grieving friend, to hold space for the complex whole of their story.

Grief Coaching and Resources

Grief can be overwhelming, and our culture does not provide many wholehearted narratives. Here are some available resources.

Tiffany Sostar (that’s me!) There are two services I offer that can be helpful with grieving. The first is the backbone of my business – self-care and narrative coaching. I can help you figure out how to take care of yourself through the process.

The second is a more specific thing – If we are dealing with long-term grief, or if we want to feel closer with our lost person again, narrative therapy offers a method called “re-membering conversations” – where we bring a member of our community close again through a guided discussion of the relationship, the cherished memories, and the mutual impact of the relationship on both lives. This can be a cathartic and empowering experience.

Rachel Ricketts of Loss and Found. Rachel is an intuitive grief coach in Vancouver, BC. She is a Black woman with a particular passion for working with people of colour whose experiences of grief are informed by generations of oppression, grief, and trauma. I found her through Black Girl in Om, where her post “On Staying Up: How To Take Inventory of Your Grief and Celebrate Through Your Struggles” really intrigued me. She has a 10-week online course coming up on Jan 21. She also offers one on one support for people who are grieving, or who are supporting someone who’s grieving.

Refuge in Grief. RIG has a wide range of articles and resources on the topic of grief, and it can be a little overwhelming to dive into, but if you have the energy, there’s a lot of good stuff there. This article on helping a friend who is grieving during the holidays is approachable and helpful.

What’s Your Grief. What’s Your Grief is another site with a wide range of information on various grief-related topics.

I also found this Brain Pickings review of Meghan O’Rourke’s The Long Goodbye really beautiful. I haven’t read the book yet, but I will someday. The quotes pulled here are poignant.

What other grief resources have you found helpful?

by Tiffany | Jan 4, 2018 | #100loveletters, #tenderyear, Business, Coaching, Health, Interviews, Neurodivergence, Online courses, Patreon rewards, Self-Care Salon, Step-parenting, Workshops, Writing

I’ve spent the last couple days mapping out my immediate upcoming projects. It’s pretty exciting, and there are many things coming up that you can be part of!

Check these projects, collaborations, and events out, and get in touch with me if there’s anything that piques your interest.