by Tiffany | Dec 9, 2018 | Feminism from the Margins, Grief, Intersectionality

This post is part of the Feminism from the Margins series. Normally, these are guest posts. This month, this is a post by Tiffany Sostar. Tiffany is a settler on Treaty 7 land, the traditional territories of the Blackfoot, Siksika, Piikuni, Kainai, Tsuutina, and Stoney Nakoda First Nations, including Chiniki, Bearspaw, and Wesley First Nation. This land is also home to Métis Nation of Alberta, Region 3.

This post is an expansion of a social media post I wrote on December 6. December 6 is National Day of Action and Remembrance on Violence Against Women, and the anniversary of the école Polytechnique massacre in Montreal.

Here is the post from December 6:

29 years ago was the école Polytechnique massacre in Montreal.

I am remembering the women who were killed 29 years ago for being in “men’s” educational spaces.

Geneviève Bergeron (born 1968), mechanical engineering student

Hélène Colgan (born 1966), mechanical engineering student

Nathalie Croteau (born 1966), mechanical engineering student

Barbara Daigneault (born 1967), mechanical engineering student

Anne-Marie Edward (born 1968), chemical engineering student

Maud Haviernick (born 1960), materials engineering student

Maryse Laganière (born 1964), budget clerk in the École Polytechnique’s finance department

Maryse Leclair (born 1966), materials engineering student

Anne-Marie Lemay (born 1967), mechanical engineering student

Sonia Pelletier (born 1961), mechanical engineering student

Michèle Richard (born 1968), materials engineering student

Annie St-Arneault (born 1966), mechanical engineering student

Annie Turcotte (born 1969), materials engineering student

Barbara Klucznik-Widajewicz (born 1958), nursing student

I’m thinking about all the women who face misogyny and violence in their places of work or learning or living.

And I’m thinking about how heightened that threat is for women who are further marginalized.

My work over the last few months has focused on responding to the fear, despair, and grief over the state of political, economic, and environmental climate shifts.

Today, I am sharply reminded that what so much of what we see in in the news is not new. Some of us, who have been sheltered by our privilege, are in a new experience of apocalyptic fear and violence but for many Indigenous and Black and trans and refugee and queer communities, this is not new. Seeing these names, and grieving for them, I am also thinking about all the trans women who are never memorialized in this way because their womanness is erased in media coverage of their deaths, and about all the Indigenous women whose disappearances are not properly investigated, and about Black women who are also targeted and killed.

It’s harder to memorialize the slow massacres. That’s further injustice.

Other parts of this current context are new. The state of the environment, the wealth gaps that are widening and contributing to harm, the complex crush of late-stage capitalism adds complexity to the old issues of oppressive violence. This makes me think about the increasing rates of violence that marginalized communities face and are likely to face in the coming future.

It’s a heavy day.

Resist and respond to misogyny wherever you find it.

Stand up for women, femmes, and non-binary folks.

Stand up for women in spaces they aren’t “supposed” to be – for marginalized professional women, for women in STEAM, for women in sports.

Stand up for women who aren’t white or straight or cisgender or abled or neurotypical.

Be kind to the women, femmes, and non-binary folks in your life. It’s ugly out here.

After writing the post, I was reflecting on anti-feminism, and on white feminism and other mainstream feminisms that end up doing violence, especially Sex Worker Exclusionary Radical Feminists (SWERFs) and Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists (TERFs). I was thinking about how challenging it is to respond to injustices within the community while also responding to injustice directed at the community.

The Feminism from the Margins series of posts has, so far, focused on responding to injustices within the community, and this is a critical and necessary focus. Harms and injustices are perpetuated within feminism by feminists who do not actively respond to their own privilege and dominance. We see this over and over again, notably this week from Lena Dunham who has spoken at length about her feminism and yet lied in order to discredit a Black women who came forward about her sexual assault by a white man who was a friend of Dunham’s. (This article from Wear Your Voice magazine goes into detail and history about this specific issue and the long pattern of white feminist erasure and violence.)

I’m also thinking about the fact that the école Polytechnique massacre was specifically anti-feminist. It was not just anti-woman, it was anti-feminist.

This is important. Anti-feminist violence is something that our community is facing, even as we are struggling to address and redress the harms done by feminists to other women and marginalized community members. This month, thinking about this project, thinking about feminism from the margins – feminism that happens on the margins, where we are more at risk, more vulnerable, more likely to face the kinds of slow and unmemorialized massacres of structural and systemic violence – I am wondering how to talk about violence within the community and also acknowledge violence directed at the community.

How do we respond in ways that invite community care, collaboration, and collective action?

The reason it feels important to talk about the anti-feminist violence is because 29 years ago the anti-feminist nature of the violence was erased, and it often continues to be erased today.

Melissa Gismondi at the Washington Post writes:

In the days, weeks and years following the attack, the question of whether it was anti-feminist became a point of contention.

Feminists pointed to some important evidence suggesting it was. They stressed that Lépine explicitly targeted women by segregating them from their male peers. Before he started shooting, he shouted, “You’re all a bunch of feminists, and I hate feminists!”

Lépine also left a suicide note that listed an additional 19 women he wanted to murder, including Francine Pelletier (a prominent feminist activist and journalist), a Quebec cabinet minister and some female police officers who’d angered Lépine by playing in a work volleyball league.

And yet a range of people from pundits to physicians saw the shooting in a different light. They denied the “political reasons” of the crime that Lépine himself espoused, arguing that the shooting was about the psychological collapse of one man who couldn’t find his place within society. For instance, a Montreal psychiatrist proclaimed in Montreal’s La Presse newspaper that Lépine was “as innocent as his victims, and himself a victim of an increasingly merciless society.” According to Pelletier, a Quebec City columnist also alleged that “the truth was that the crime had nothing to do with women.”

The brilliant Anne Thériault writes at Flare:

But if there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s that we can’t fight against violence that we can’t name. So this year I’m saying what I’ve been too afraid to articulate until now: Marc Lépine was hunting feminists on December 6, 1989. His followers are still hunting feminists, and they don’t care what labels those feminists use. We can’t save ourselves by trying to appease men who see us as less than human. All we can do is keep rattling the cage until it finally breaks.

I suspect that we can work to resist violence both within our communities and directed at our communities by naming what is happening. And we can trust people to be able to name the problems that they are facing – we can listen to sex workers rather than naming their problem for them and then trying to “rescue” them from a problem we have misnamed and misunderstood; we can listen to Black women and Indigenous women and other women of colour rather than naming their problems for them and demanding that they wait their turn until “women” are “equal” before they can also demand justice; we can listen to disabled communities, neurodivergent communities, mad and neuroqueer communities, queer communities. It’s not just about naming, it’s also about who is allowed to give the name, who is treated as the expert in their own experience.

The reason this project feels important to me, and the reason I am so thankful for other projects that are intentionally bringing marginalized voices to the center (projects like Cheryl White’s Feminisms, Narrative Practice & Intersectionality series), is because there is so much violence and threat right now. And it is coming from so many directions.

There is so much fear. There is so much fragility. There are so many invitations to feel like a failure, and to give up. There is so much perfectionism, so much anxiety about saying the wrong thing (and a lot of this anxiety is warranted!)

So many of us are so afraid.

So many marginalized communities have been silenced for so long.

It feels important to make space for many voices. To hold each other accountable. To care for our communities in ways that are both robustly justice-oriented and that also maintain the dignity of our community members.

That’s the goal of the Feminism from the Margins series, and it feels important this month, as I think about violence, and fear, and how we remember.

In another post Anne Thériault gives necessary context and humanizing personal details to the list of names, “trying desperately to remember them as bright, lively young women instead of statistics.”

It’s worth reading, and it’s worth thinking about in terms of how we engage with each other, as well. When someone is sharing their pain, how do we respond? When someone is angry, how do we hear it?

The silencing that feminists experienced after the Montreal massacre is something that is still happening, both within feminisms and directed at feminists.

We can practice community care by learning from how we have been hurt, and by not silencing marginalized communities who are trying to tell us how they have been hurt and what they need in order to find justice.

We can listen to the margins.

We can do better.

Stasha, writing about the massacre, said:

1989 was probably the first time that I wondered why men hate us enough to kill us. I was nine. I think of the daily fear that Indigenous, Black and trans women face. I think of the next generation growing up with knees-together judges and pussy-grabbing presidents.

And I cry with frustration that I can’t offer anything better to the next generation. It makes me furious to watch them feeling hunted, and to only be able to support in the aftermath, with no ability to prevent. It hurts me so much that this is seen as a women’s issue, how fucking absurd.

On this day, I think about strangers trying to kill us for living fully, but I always return to the attacks from people who say they love us, because I can’t get over that there are no safe places.

We have to be part of the work of creating safe places.

It’s not good enough the way it is now.

This post is part of the year-long Feminism from the Margins series that Dulcinea Lapis and Tiffany Sostar will be curating, in challenge to and dissatisfaction with International Women’s Day. To quote Dulcinea, “Fuck this grim caterwauling celebration of mediocre white femininity.” Every month, on (approximately) the 8th, we’ll post something. If you are trans, Black or Indigenous, a person of colour, disabled, fat, poor, a sex worker, or any of the other host of identities excluded from International Women’s Day, and you would like to contribute to this project, let us know!

Also check out the other posts in the series:

- All The Places You’ll Never Go, by Dulcinea Lapis

- An Open Love Letter to My Friends, by Michelle Dang

- Prioritizing, by Mel Vee

- Never Ever Follow Those White Kids Around – a brief personal history of race and mental health, by Mel Vee

- Living in the Age of White Male Terror, by Mel Vee

- I Will Not Be Thrown Away, by Mel Vee

- Selling Out the Sex Workers, by X

- Holding Hope for Indigenous Girls, by Michelle Robinson

- Three Variations on a Conversation: cis- and heteronormativity in medical settings, by Beatrice Aucoin

- Lies, Damn Lies, and White Feminism by anonymous

- Responding to the Comments, by Nathan Fawaz

Tiffany Sostar is a narrative therapist and workshop facilitator in Calgary, Alberta. You can work with them in person or via Skype. They specialize in supporting queer, trans, polyamorous, disabled, and trauma-enhanced communities and individuals, and they are also available for businesses and organizations who want to become more inclusive. Email to get in touch!

by Tiffany | Nov 22, 2018 | Downloadable resources, Identity, Intersectionality, Writing

Image description: A cup that says “be strong”. Text block reads: What does strength look like for women, femmes, and non-binary folk when it is not centered on the endurance of pain?

This document is also available as a PDF, which can be downloaded and freely shared. This PDF will be updated with stories that are shared in response, and will eventually be available as a printed zine.

What does strength look like for women, femmes, and non-binary folk when it is not centered on the endurance of pain?

This question is not meant to erase the strength that is so heavily present in our need to endure, to survive, and to carry on from the violences in our lives, but it is meant to ask what else is there? What else do we have to offer? What forms of strength go unnoticed even to ourselves?

Strength

by Andrea Oakunsheyld

While processing a very impactful breakup, I talked to myself a lot. I listed all the things that I have already been through and come out the other side. I talked to myself about the things that I have already managed to endure because enduring those meant that, in my mind, I should be able to endure this.

I was so lucky to be thoroughly caught by my communities in this time, and to have many conversations about myself and my broken relationship. These conversations were centered largely on endurance and the ways in which my communities perceived me to be a strong individual.

After weeks of contemplation and conversations, I came to the realization that I was only seeing my strength through taking stock of past endurance of pain.

It occurred to me that this was a very feminized account of strength, and one that I was sure many women, femmes, and non-binary folk could identify with. It’s certainly not the definition of strength that I would instinctively ascribe to men or the masculine-identified, and I became distressed that I had such a narrow conception of my own strength, and by extension, the strength of women, femmes, and non-binary folk in my communities.

It makes sense for endurance and the endurance of pain to be an indicator of strength, but not the only indicator of strength that feminized folks perform. So, I was left to ask myself – what does strength look like for women, femmes, and non-binary folk when it is not centered on the endurance of pain?

This question is not meant to erase the strength that is so heavily present in our need to endure, to survive, and to carry on from the violences in our lives, but it is meant to ask what else is there? What else do we have to offer? What forms of strength go unnoticed even to ourselves?

My percolations on feminized or non-binary strength have led me to reassess many aspects of social life that I had already valued but never seemed to internalize as strength.

When interrogating this topic for myself, I found that strength comes in the very ordinary navigation of every day. It is in the empathy that we offer long before we are coerced. It is in the emotional labour that we offer up to ourselves to heal our traumas, and to our communities to create a network of support. It is in sensitivity. It is in community care because we know that to alienate one another is to bring destruction. It is in self-care, the other side of the coin, in which we offer ourselves the same care we offer to others. It is in caring for our bodies, minds, and spirits in the most intimate way because they are ours. It is in the contract with our network that states that we will give what we have to offer and will respect each other enough to say when we need recovery of our own. It is in boundary setting because setting our own boundaries better equips us to recognize and honour the boundaries of others.

Strength is in the feminized labour of the hearth and home. Maintaining basic needs and basic comforts. It is in the nurturing of the family that some of us provide (chosen and blood family alike). It is in activism where we rally around those in the margins and we demand better. It is in questioning of the fundamental systems of our everyday life and choosing an alternative path. It is in our differences. It is in the bravery we show when we must face the danger of being our non-normative selves and practicing our non-normative lives.

Strength is in every heart learning its own worth and it is also in those who are still discovering it. Strength is in the ability to be humbled and to admit to wrongdoing. It is in the commitment to do and be better. It is in the accountability we have to those around us. It is in being grounded in the earth and in community. It is in making a proper home in our own skin and being in our own bodies, in the ownership of our bodies and our sexuality. It is in sexual healing, however that looks. It is in showing ourselves self-compassion when we can’t quite manage self-love. It is in going out into the world every day to face down the very violences that have so far defined our strength.

Our strength is in the queer, the disabled, the racialized, the poor, and the further marginalized, but not merely because of what they, and we, have endured. Our strength is in us because of the unique things that we have to offer parallel to enduring pain and violence, the things that bring their own virtues.

After percolating on all of these things it seems a grim shame to me that these were not included in my original conceptualization of my strength. These other indicators of strength are important to conceptualize, at least in part, outside of the endurance of pain.

Stories of our strength: women, femmes, and non-binary folks respond to the question

Kassandra:

Your question reminded me a story from my family. The period of Junta in Greece, my mom and her brothers were chased and some of them exiled for their left-wing political action. In her 20’s my mom was the only woman in the family who decided to escape to another country in response to the daily interrogation and police abuse. Although she was coming from a working-class family with no educational background, while she was in a foreign country, being a woman and not being able to speak the language, she decided to be the first in the family who will try to study. However, she faced lots of racist attacks both for her race, her class and her gender. She was scared, and lonely, and in pain. One day after an incident when someone mocked her for being Greek, poor, incapable woman, she got truly devastated and she went to meet one of her brothers who was also staying in the country. Her brother told her a phrase that I’ve seen my mother return to whenever she is looking for her place of strengths to stand on. He said “whenever someone mocks you for your class or your race or your gender, remind yourself of Lernaean Hydra (from the Greek mythology). They might think that you are beheaded, but like Lernaean Hydra once a head is off, another one will grow and then you will still have voice to protest. Take your time to let your next head to grow and then protest!’ I don’t know if that answers your question, but I guess what I have learnt about what strengths look like for my mum is that it’s related to protest in its own pace and as an ongoing life process. I hope that make sense.

Anita:

I really love Kassandra’s contribution. It connects to how I relate to the idea of strength being social more than individual. There is a lot of pain and difficulties for marginalised peoples and the dominant discourse is to endure and especially endure alone. I take a different stance. Sometimes we have to find someone else we can share with. Even when family lets you down, work colleagues or fellow activists disappoint us there is someone, an exception who we can connect with, even if only in memory. Sharing strengthens us and undermines isolation. Sharing can promote organisation and often brings along laughter and solace. In my group of sisterfriends we practice sharing and thinking through actions, consequences etc. In other words, we get practical.

Laura:

For me strength can be a metaphor of structure (this could be organic and growing or built of materials or simply a metaphor of posture and position which allows us to hold ourselves strong) which makes other things possible – connection with others in the present, a centring of the ways we prefer to be ourselves, enough places to hold hope and joy, connection with our important histories, enough stability to be open to experience and change, creating spaces for others to grow, quiet places to reflect and reconsider, as well as endurance.

Marta:

Strength can be seen as not giving up on dreams. A metaphor can be like the little green plant raising from the snow and with time becoming a bush, a tree a flower. Follow our heart´s call. Birds gathering branches and things for a nest where they are going to put their eggs that will support babies someday.

Jessica:

My ability to set my ego / self aside to become wholly present to the experience of other life; my plants and heir happiness in new soil, my friend as they live their lives. It requires strength from me emotionally and psychologically to take a time out and allow myself to connect fully to another reality, immerse in it, ask myself IF in ways that aren’t about psyching myself out, but are about connecting within equally without. Also, physically, finding joy in the added effort of another 5lbs more. Am I understanding and getting it, or did I miss something?

Jacie:

Ease to explore & realize your priorities OR in other words, liberty of determination

My daughters would say it’s in my smile–perhaps it’s in acceptance?

Juliana:

Knowing your truth and priorities and being able to hold on to them even in the face of lies and distractions that society aims at you.

A Conversation

Shannon: It seems tied to power a lot in jobs and social power too. It’s not an easy question to answer though. The main places my brain is jumping to are enduring pain or else just professional type athletes. It’s like a brain-teaser. At first, I thought maybe there was a trick to it. Maybe there still is.

Tank: Challenging the status quo. Challenging dichotomy. Challenging the notion that we are not part of nature. Nurturing power-with instead of power-over/challenging hierarchies. Loving self, despite patriarchies constant attempts to tell us that we have no value.

Shannon: I interpreted this so differently than you and I’m pretty sure it’s because I feel completely powerless the vast majority of the time

Tiffany: That’s so valid, Shan. It kind of IS a trick question, except the trick isn’t in the question, it’s in the way so many of us have learned to view our strength only in terms of endurance and pain.

Tank: Well that is an important finding! Power is very relational, for example my white or class privilege makes it safer for me to challenge. The question helped me realize that I mostly frame this idea of ‘strength’ as endurance of pain. All interpretations help to understand a concept this big.

Shannon: Tiffany, no but it was that I didn’t think of it in terms of *my own* strength at all OR what *I* think of as being strong. Just other people. I missed the point so much that I didn’t even get tricked by the trick. I wasn’t even on the same page.

Shannon: Tank, yeah it was just surprising to me and everything makes me cry so that was not surprising to me at all.

Tank: Shannon, you pointed out how power works systemically = very useful. It is revolutionary to have this conversation about how we have noticed that pain endurance is the main definition of strength for non-men in this society. I found your thoughts very useful.

Tiffany: You noodles are making me tear up right now. I would add this moment of compassion and collaboration as one definition of strength – the strength we find together and share with each other.

Shannon: Tank, thank you

Tank: Oooooo it all makes me cry as well. Probably a strength, ha!

Shannon: Must be

Michelle:

i offer resistance in hope

i offer resistance in losing hope

i offer resistance through words

i offer resistance through silence

i offer resistance in my presence

i offer resistance in my absence

you can offer all your hate,

and still i will offer you my resistance

I don’t think I’ve ever really intentionally examined the multiple meanings of strength, particularly outside the idea of enduring pain. But of course, there are other definitions. This reflection has me thinking about ‘giving up’ and resignations as strength. I wrote this poem during a difficult time where I made the decision to resign from an organisation I had dedicated so much time and energy to. At the time, I felt like resigning meant that I was giving up on the struggle, abandoning the women and non-binary folk I was in solidarity with.

I stayed for so long because I felt that surely my cis-gendered, professional privilege and 9 years experience in the sector and dogged determination to create change would help transform the institution. Staying and therefore enduring pain was in part an act of bearing witness, part stubbornness, part hope for change, and part inflated responsibility.

Feminist work within institutions demands ongoing resistance and endurance, but as Sara Ahmed asks: ‘But what if we do this work and the walls stay up? What if we do this work and the same things keep coming up? What if our own work of exposing a problem is used as evidence there is no problem? Then you have to ask yourself: can I keep working here? What if staying employed by an institution means you have to agree to remain silent about what might damage its reputation?’

Staying was strength, but it also became complicity. My position as a woman of colour and public support for the gender diverse community was being used as evidence that there was no problem with racism or transphobia. In the final months of my employment, it had dawned on me that my presence was inadvertently upholding the walls of Colonial Patriarchal Feminism2 and trans exclusive radical feminism. The ongoing denial, gaslighting and attacks made me realise that I was being played.

So I quit, I resigned.

A couple of months later, I held a retirement party and invited all my friends join me in quitting with giving any more time and energy into systems that sustain the white cis-heteropatriarchy. So, with a baseball bat and some unwanted fruit, we took to the field and smashed all the symbolically toxic fruits from our lives. It was the best. I have since come to appreciate that resistance and strength comes in many forms, both in staying and leaving. But for now, I feel a great sense of freedom and pride that I can still do feminist work, and I would say more effectively and joyfully, outside of those systems.

[1] https://feministkilljoys.com/2016/08/27/resignation-is-a-feminist-issue/

2 Cheree Moreton coined the term Colonial Patriarchal Feminism or Colonial Patri-Fem for short, to describe how white feminists stigmatises and silences the one black voice in the organisation/environment

Miri:

Strength looks like self care, caring for friends and lovers, building family, resisting heteronormativity/racism/ableism/colonialism. Being out, embracing your identity whatever that may look like for you <3 <3 It doesn’t always have to look like enduring pain.

Suzanne:

I think strength for femmes is in prioritizing yourself and how much of your time and energy you offer to the outside world and why you offer it. So many femme folks feel like they can’t say no, or offer their time and energy to everyone who asks without prioritizing their own needs first, or evaluating whether they actually want to participate. The times I feel like I really identify strength in femmes is when I see someone identify an unreasonable ask and stand their ground, or prioritize their own well being over someone else’s. I think what makes it so magical when femme folks do this is that it usually isn’t done in an aggressive way, it’s the way many femmes can express themselves empathetically and not need to sacrifice vulnerability and emotionality in the process.

I can relate almost anything back to Buffy the Vampire Slayer, but she has a line where she tells the other slayer Kendra that her emotions are what give her strength and that she is lucky to have them. For me, as someone who has struggled with mood issues and is definitely pretty sensitive and empathic, I totally identify with this. I feel EVERYTHING so deeply, and I have been told for so long that this is wrong or a burden to others, and frankly that’s BS. My emotions are a huge factor as to why I’m a bad ass and why I see myself as strong. Not just in enduring pain, but in being aware of how every little thing affects me, so I have learned to use this in the way that I take in new information and learn, and the ways I interact with the world. Masculine strength always seems to be tied to suppressing and ignoring emotions, and femme strength is emotional intelligence and awareness. Strength is seeing how emotionality and “rationality” are woven together, and using that intelligence to make the tough calls. It’s seeing the entire picture when the world tells you it’s not there.

Wow that all just came out of my head all at once, so thank you for that prompt and I hope it’s helpful!

Candice:

When I was first given this question, it was very difficult for me to think of feminine strength that didn’t involve any pain at all. After talking with my family, I realized one of the main strengths of a woman is their amazing willpower. It is one of the things that allows us to be able to function through unimaginable pain and discomfort.

I believe most of our best qualities comes from our ability to be resolute once we’ve made up our minds to do something.

The strength to be able to create art, relationships and solutions out of little to nothing.

The strength required to bear the worries and problems of those around us when we choose to take on a nurturing role.

The strength to persevere through mentally and emotionally challenging spots in our lives.

The strength it takes to search for who you are and to give yourself space for mistakes as well as growth.

I find often times we discredit some of our strength and power because we aren’t functioning at the levels we expect of ourselves. But I have discovered that sometimes our strength can come from saying no, or from recognizing our limitations and allowing ourselves to exist in respect to that limit instead of overdoing it.

Like with any strength, it takes time to mould and develop a strength of mind. I think that’s why some of the most admired women have had decades to grow in their wisdom and willpower. However, unlike other strengths, the power of our minds deepen with time and experience.

Kalista:

Strength is existence. Existing as ourselves, fully and completely, without being property or object. Strength exists in the wholeness of true friendships and loving relationships that create space for us to be unabashedly ourselves. Strength exists in every pore of our body when we defy societal expectations, when we research our issues, when we change patriarchal policies, and when we find ways to keep on existing even when the world tells us not to or that we can but just not here. Strength is existence.

Erin:

When I think of female* strength I think of the strengths and characteristics that distinguish females from males traditionally. I think of traits that if they were more celebrated in leadership roles and sought after we may have a world with less war and conflict. Obviously there are always exceptions to these norms.

The traits of female strength I think of are compassion and patience. An often natural nurturing ability that sympathizes and allows women to be great listeners. The ability to multi-task and compartmentalize. The tendency to be able to see the bigger picture, see a situation from another perspective or see the effects of a decision much later down the line.

I think these are the core ones at least!

* Traditional definitions of “female” and “male” often include cisnormative understandings of sex and gender. Talking about these traditional roles can be important, especially when we understand that these understandings are not situated in any objective reality. This resource is intentionally trans and non-binary inclusive.

Tiffany

Sometimes I know that I am strong. But so many times, I do think of this strength in terms of what I have endured. I think about it in terms of pain, and struggle, in terms of what I have survived. I think about making it out alive, through multiple serious depressions. I think about the hostile voice that I lived with for a period of time, and that occasionally returns. I think about my history of self-harm, and I think that I am so strong to have found ways to alchemize all of that into the work that I do now as a narrative therapist and community organizer. I think, good job, me.

But when Andrea shared this question with me, it resonated somewhere deep in my heart. I wanted to find answers for my own strength, beyond these ideas of pain, struggle, endurance, survival. I wondered if there was anyway to understand my relationship to strength outside of these ideas.

And when I sent the first draft of this project to Andrea, she said, “Are you not doing your own entry in the project though, dear?”

It was hard to find these stories in my own internal library. They were quiet.

I thought about when I have felt my strength come close to me while I am joyful. I thought – sometimes strength is laughter. A good strong laugh is something I have had since I was a child! That’s strength, too.

And I thought about strength in hope. I thought about spending time with small children. My niephlings, and other children in my life. I thought about the strength of holding space for their joy, and for their learning. The strength of imagining a world with space for them despite my own fears for the future. I thought – sometimes strength is choosing hope when despair is equally close at hand.

I also thought about how sometimes strength is easier to access when I’m rested, peaceful, and at ease. At first, this thought made me uncomfortable. I thought, does this mean that I’m not really strong when I’m struggling? Does this mean I’ve been wrong about everything about myself? But I don’t think that’s the case.

I think that there are many different ways to be strong, and that one way of being strong is by allowing myself some ease. Sometimes when I feel rested and supported and cared for, that’s when I feel strongest.

And then there’s that little piece. “When I feel supported and cared for.” That part challenges the internalizing narratives, the individualizing narratives about strength. What might happen if I didn’t need to be strong on my own? What if I could imagine strength in community, strength in connection?

It’s not always about what I endure alone. Sometimes it’s about what I co-create with my communities.

Exploring your own strength

These are some questions to help you explore your own ideas about strength beyond metaphors of enduring pain.

- What does it mean to be strong? Are there definitions of strength accessible to you that go beyond enduring pain?

- Can you share a story of a time when you been strong in these ways? What allowed you to access this strength?

- Are there other ways to be strong?

- Who taught you about strength?

- Can you remember seeing strength in a woman, femme, or non-binary person in your life?

- Do any of these women, femmes, or non-binary folks know that you see strength in them? What has seeing this strength in their lives made possible in your own life?

- Who in your life, living or no longer living, real or fictional, knows that you are strong?

- What would you want women, femmes, and non-binary folks to understand about strength? Are there insider knowledges that you would want to share?

We (Andrea and Tiffany) would love to hear your stories of strength, and to keep this conversation about the strength of women, femmes, and non-binary folks going.

We would also love to hear any response that you might have to the stories shared in this document.

If you would like to share your response, please email it to Tiffany at sostarselfcare@gmail.com.

Andrea Oakunsheyld is a student at UBC in a Masters of Community and Regional Planning with a concentration in Indigenous Community Planning, a Fieldworker with Amnesty International Canada, aspiring theorist, community organizer and activist, bigender pagan witch, and nerd living and learning on the traditional and ancestral territory of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations. Her work includes grassroots activism, particularly in queer, women’s, and queer contexts; “calling in”; queer children’s literature and subversive literature; subversive cities; and community planning.

Tiffany Sostar is a narrative therapist, community organizer, writer, workshop facilitator, and tarot reader living and working on Treaty 7 land (Calgary, Alberta) where the traditional custodians are Niitsitapi (Blackfoot) and the people of the Treaty 7 region in Southern Alberta, which includes the Siksika, Piikuni, Kainai, Tsuut’ina and the Stoney Nakoda First Nations, including Chiniki, Bearpaw, and Wesley First Nations, as well as the Métis Nation of Alberta, Region III. They work primarily with queer, trans, disabled, neuroqueer, polyamorous, and other marginalized communities. If you would like to work with Tiffany, you can find them at:

www.tiffanysostar.com | sostarselfcare@gmail.com | @sostarselfcare

You can support more of this kind of community-led, collective narrative practice work by backing Tiffany’s Patreon at www.patreon.com/sostarselfcare

This project was initiated by Andrea Oakunsheyld in late July, and is now ready to share! These kinds of collaborative, community-led projects are among my favourite parts of my narrative work, and although they often take months or years to complete, it is always incredibly rewarding. If there’s a topic like this that you want to talk about turning into a project like this, get in touch with me!

by Tiffany | Nov 9, 2018 | Intersectionality, Narrative therapy practices, Possibilities Calgary, Writing

Image description: An ornate pink, blue, and white background. Text reads – Solidarity : a Possibilities Calgary event in solidarity with the trans community : Nov 20, 2018 | Loft 112 | Writing a collective letter in support of the trans community on Trans Day of Remembrance

November’s Possibilities event falls on Nov. 20, Trans Day of Remembrance. (The official Transgender Day of Remembrance event happens in Calgary on November 18 at 1:30 pm at CommunityWise.)

Possibilities, although we are a group for and by the non-monosexual communities (bisexual, pansexual, asexual, and otherwise non-monosexual), has always been trans-inclusive, and many of our founding members are trans. This year, we will host a conversation with the goal of writing a collective letter of support from our community to the transgender community.

This is particularly important this year because transgender rights are under increased threat, very actively in the United States and looming on the horizon if conservatives gain power in Alberta and in Canada. This is a hard time to be a trans person looking to the future, and the goal of this event is to document our collective support for our trans community members and for trans folks beyond our bi+ community.

This event is open to transgender and cisgender members – we will be expressing our support both for and as transgender folks, and support from many parts of the community is important.

This collective letter will be part of the ongoing Letters of Support for the Trans Community project.

Notes about Possibilities:

There is a small fee associated with renting the space, and you can support the event by either donating at the event or becoming a Patreon supporter.

We have a focus on self-care and self-storying for the bi+ community (bisexual, pansexual, asexual, two spirit, with an intentional focus on trans inclusion), and a new framework for sustainability (you can now support this work by backing the Patreon).

There is no cost to attend.

This is an intentionally queer, feminist, anti-oppressive space. The discussion will be open, as they always were, to all genders and orientations, as well as all abilities, educational levels, classes, body types, ethnicities – basically, if you’re a person, you’re welcome!

These discussions take place on Treaty 7 land, and the traditional territories of the Blackfoot, Siksika, Piikuni, Kainai, Tsuutina, and Stoney Nakoda First Nations, including Chiniki, Bearspaw, and Wesley First Nation. This land is also home to Métis Nation of Alberta, Region 3.

It is important to note that Possibilities Calgary is a community discussion group and not a dating group.

by Tiffany | Oct 9, 2018 | Feminism from the Margins, guest post, Intersectionality

Image description: A tweet, retweeted by Red Thunder Woman (@N8V_Calgarian).

This is a guest post by Nathan Viktor Fawaz. Nathan is a settler on Treaty 7 land, the traditional territories of the Blackfoot, Siksika, Piikuni, Kainai, Tsuutina, and Stoney Nakoda First Nations, including Chiniki, Bearspaw, and Wesley First Nation. This land is also home to Métis Nation of Alberta, Region 3.

This post is part of the Feminism from the Margins series.

This post is an expansion of a comment that Nathan was going to share on this CBC article. In the article, Michelle Robinson said, “Our culture is not a costume. We are real people with a real culture and depicting it incorrectly just adds to negative stereotypes and adds to violence we face.”

The comment section on this article became full of comments that ranged from aggressively racist to casually ignorant.

Some of these comments included:

“As a doctor, ought I be offended at those who dress as doctors for halloween?”

“I’m pretty sure that most kids dress up like this or firemen or police men or… the list can go on an on… because it’s admirable, not because any racial or heritage put down. By this account even my 4 yr old son is being disrespectful?? Why is everyone quick to assume their a victim?”

“This is what causes magnified racism. There are cowboys, bakers, fat suits, etc. I could go on and on. Your indigenous clothing is chosen for its beauty. Be proud you have beautiful clothing to be replicated. I am fat and they are not wearing that fat suit because it is awesome.”

“Most cultures have costumes depicting them. Shouldn’t it be seen as celebrating the culture?”

Nathan did not share this comment, in part, because it is too long for a comments section, and in part because this is such a tricky topic to speak about as a settler. In many ways, this Feminism from the Margins post is different from others because it is the margins aligning with the margins to speak to the centre, it is an attempt at allyship and accompliceship from a position of different marginalization.

Nathan wrote:

I wanted to respond to these comments, because I am working on decolonizing practices and incorporating them into my everyday life. Using my privilege to comment, as a settler, on news articles and social media is one small way I am learning how to be clear and unapologetic about pointing out ways in which individuals are reinforcing the oppression of indigenous people while also trying to keep people (in this case settlers) engaged in thinking about how what they have said is out of line with how they might think of themselves as good people.

I do not do this often, because as someone experiencing disability, and as a non-binary transperson of mixed race, I do and have experienced an amount of violence on these threads, and I still struggle to read them.

I am writing about how, as settlers, we are expecting that Indigenous people, who are still in the same generation of people with direct experience of residential schools, let alone having descended from parents and grandparents who were in those schools — schools that were so harsh, in part, in order to make Indigenous people more like white people — we are expecting people who experienced abuse and torture to heal. I think we use the phrase: ‘get over it’.

And, I can see a good intention there. Trauma that isn’t transformed gets transmitted. But, being human, we all know how hard the work of transformation is.

Having never attended a residential school, nor having been raised in whole or part by someone who has, in a community of people who have, I can only think about this from an outside perspective and in terms of analogies.

It seems to me that for many years, Indigenous people have had their suffering denied, and in fact have been told that they should be grateful for their treatment, and this seems to me somehow related to the way that many marginalized people are denied self-knowledge and accurate medical care.

So, Indigenous people have worked to find language for a problem that was imposed on them and then denied by the people who imposed the problem.

When something similar happens to anyone, for example, a person seeking medical care for anything related to a brain (trauma, concussion, mental illness, injury), first we experience our health problem, and then we learn about it, and then we accept we have to do something to address it, then maybe we plan, and then we take a first action. And often, this first action is met with resistance by people in power. And sometimes also met with internal resistance, because we have not learned how to trust our own self-knowledge, and even our own dignity, or even our own integrity. I know many people who can attest to this. Many people’s experience of this is denied because doctors are supposed to be the experts, and people’s self-knowledge is often denied. As Indigenous self-knowledge has been repeatedly denied, and rendered invisible, both by people in power and people watching from the outside.

This can happen even with the best of intentions, and even by people who are well-trained in their fields. This can happen even with the best of intentions, and even within people who think of themselves as strong, who do not like to complain or raise a ruckus. The invisibilization of Indigenous experiences has been baked into our education systems, our political systems, our healthcare systems. I’m not making this analogy in an effort to devalue the knowledge of doctors, policy makers, and other authority figures, but rather to note that sometimes things are missed, and by things, I mean people and their experiences. These missing people and their experiences then become rendered as non-existent, non-compliant, or insignificant outlier rather than acknowledged as missing. Unacknowledged people and their experiences are being overwritten by what is often called the ‘common-sense’ understanding of how things are into the fabric of Hallowe’en costumes, postcards, snow globes, the names of roads, healthcare policy, access to housing and clean water.

It seems to me, that Indigenous people have a hundreds-year long history of being taken from, spoken for, and assimilated into settler culture and, it seems that Indigenous people are doing the work they need to in order to assess, make plans, and take action toward healing.

It seems to me that Indigenous people have a 112 year long wound that has been inflicted and re-inflicted on them, and that has been denied over and over, and that one part of this wound – the residential schools – only officially ended 22 years ago. Through this time, they have had the experience of being told their personal integrity is inferior to settler integrity, and that their dignity cannot be earned from us, no matter the effort.

If Indigenous people do have a history of experiencing undignified treatment and are taking collective and individual acts of integrity to reinforce the boundary of dignity, then, it seems to me, we are the people who can either acknowledge this fact or continue a history of denial.

I cannot undo hundreds of years of colonization. But I can do present day work to separate the past and present by taking a stand with my own integrity and saying: Indigenous people are calling for these costumes to be taken off store shelves, they are calling the their right to sacred practice, which is parodied in these costumes, to be restored to them.

I cannot change what a priest at St. Anne’s might have done, but I can choose to not buy a halloween headdress, or white sage, with almost no effort.

Like, I had to listen to someone explain why these costumes are a problem. Which took three minutes of time. And then simply not buy something.

This is much less dedication than it takes for me to make breakfast in the morning.

No one person can give another their dignity. But when someone, like Michelle is doing, stands up to claim it, I can certainly listen, consider the information, and support her in claiming it.

I can work to acknowledge and honour the history.

And I am delighted to do so.

I have noticed that many people do not share my delight or my perspective. And so I am wondering if you can help me understand the needs that are informing your frustration and anger and irritation.

I do not want to change your mind. And I do not want you to change mine. Because we could only ever both be defensive in that context, we could only ever fight: me to be heard, and you to be right, or vice versa. So, let us speak in the space between minds. In the pause that exits between attack and counter-attack. We just have a split-second, don’t you see?

Let’s pause it right here.

I would like to know more about your integrity. About what makes you the good person you are and how that lines up with what you have written here today.

I do not expect much in the way of exchange here. This is a comment section after all, but, I thought I would ask. Maybe there is some wounding in your world, maybe some healing transformation you are trying to make that I am not seeing.

Please help me understand.

Now. Don’t kid yourself. We cannot stay in this place of pause forever. At some point, we will each have to decide in thought, word, and action where we will land. What side we will end up on. But, for now, we have a moment, a breath, five minutes between meetings to ask ourselves if our thoughts, words, and actions are lining up with our intentions and our values.

People writing these comments wrote of Halloween as: fun, of costumes being celebrations of beauty. I agree. As we consider what Hallowe’en costumes we will and will not purchase, let them be fun, let them be beautiful, let them be celebrations of our intentions and values. Let them be on the right side of history.

Further reading:

- From Michelle Robinson: In light of the Truth and Reconciliation’s 94 Calls to Action; Business and Reconciliation, Call 92, Section iii, we the undersigned hereby demand Spirit Halloween LLC, End All Sales of Racist Indigenous Costumes #cdnpoli #IndigPoli Sign the change.org petition.

- Michelle Robinson’s podcast interview with Naomi Sayers of Kwe Today.

- Native Appropriations by Adrienne Keene is an important blog about native representation and the appropriation of native cultures.

- Âpihtawikosisân blog by Chelsea Vowel, particularly these posts on the topic of costumes.

This post is part of the year-long Feminism from the Margins series that Dulcinea Lapis and Tiffany Sostar will be curating, in challenge to and dissatisfaction with International Women’s Day. To quote Dulcinea, “Fuck this grim caterwauling celebration of mediocre white femininity.” Every month, on (approximately) the 8th, we’ll post something. If you are trans, Black or Indigenous, a person of colour, disabled, fat, poor, a sex worker, or any of the other host of identities excluded from International Women’s Day, and you would like to contribute to this project, let us know!

Also check out the other posts in the series:

- All The Places You’ll Never Go, by Dulcinea Lapis

- An Open Love Letter to My Friends, by Michelle Dang

- Prioritizing, by Mel Vee

- Never Ever Follow Those White Kids Around – a brief personal history of race and mental health, by Mel Vee

- Living in the Age of White Male Terror, by Mel Vee

- I Will Not Be Thrown Away, by Mel Vee

- Selling Out the Sex Workers, by X

- Holding Hope for Indigenous Girls, by Michelle Robinson

- Three Variations on a Conversation: cis- and heteronormativity in medical settings, by Beatrice Aucoin

- Lies, Damn Lies, and White Feminism by anonymous

Tiffany Sostar is a narrative therapist and workshop facilitator in Calgary, Alberta. You can work with them in person or via Skype. They specialize in supporting queer, trans, polyamorous, disabled, and trauma-enhanced communities and individuals, and they are also available for businesses and organizations who want to become more inclusive. Email to get in touch!

by Tiffany | Sep 23, 2018 | Bisexuality, Identity, Intersectionality, Possibilities Calgary

As part of the research for this blog post, I spoke with a few different people about their experiences of asexuality, bisexuality, and pansexuality. I’ve included those interviews in whole. I highly recommend reading these interviews – there was a lot there that I didn’t include in this post.

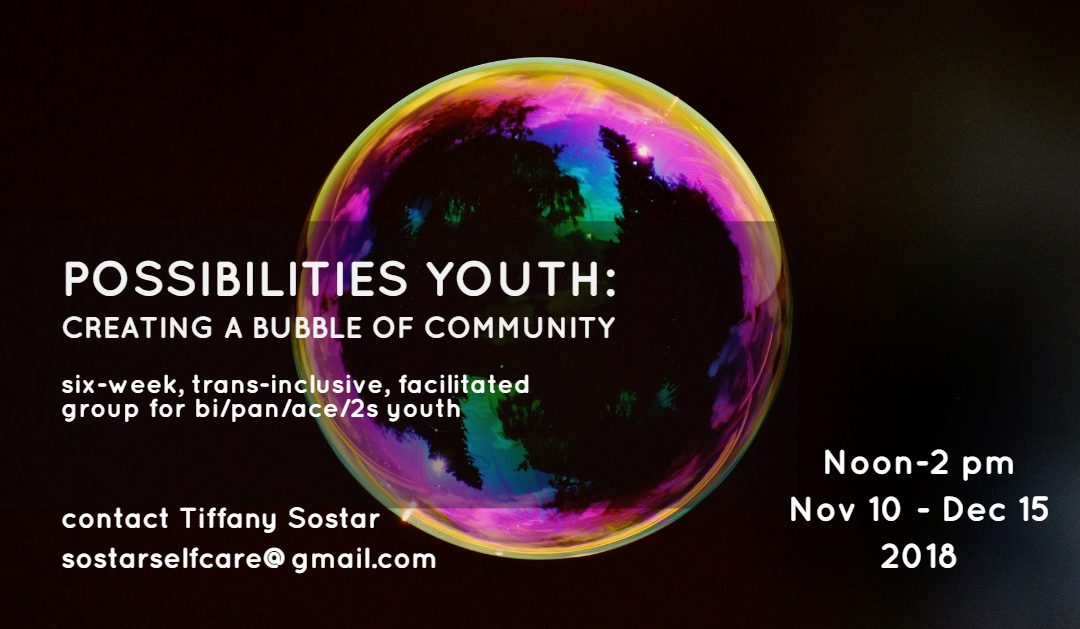

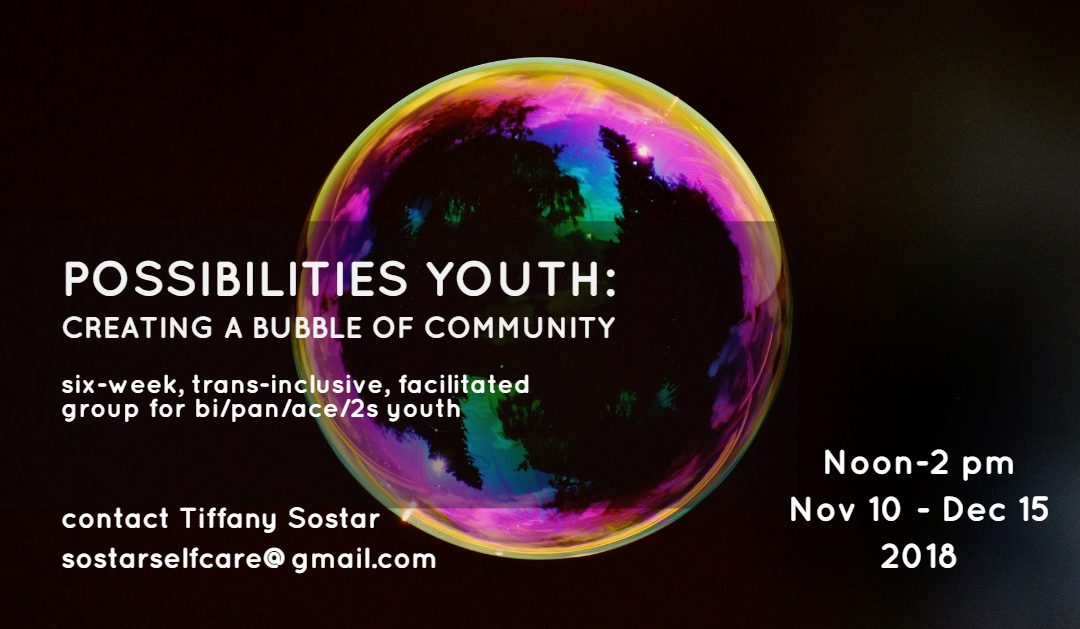

I also want to take this opportunity to highlight that Possibilities Youth is open to registrations! If you are, or know, a non-monosexual young person who would be interested in a six-week facilitated group, head over to the post and register!

It’s September 23. 2018. As I write this, I’m sitting at the kitchen table. Outside, the sky is still dark. The two dogs I’m looking after are snoozing, the furnace is on, the house is quiet except for the hum of the refrigerator and the warm air pushing up from the vents.

When I first started looking for bisexual community in Calgary, almost ten years ago, I couldn’t find what I needed. There were “LGBT” spaces (then, even more than now, Intersex, Asexual, Two spirit, and other queer identities were rarely acknowledged actively or meaningfully), but, as so many other bisexual folks have found, these tended to be “GL” spaces in practice. And even so, there weren’t many of those. A club. Some campus communities (which felt impossible to access as an adult who had never attended post-secondary at that point). Community discussion groups, but nothing that felt like it would be for me.

This is still the case for so many people in so many spaces.

The Bisexual Invisibility Report came out in the United States in 2011, and it was groundbreaking. Shiri Eisner, one of my bisexual heroes and someone I have learned a lot from (their book, Bi: Notes for a Bisexual Revolution, changed my life. This is not hyperbole.), noted that the report should have been called The Bisexual Erasure Report. I agree. It’s not that our community is invisible, a framing that consistently leads to hostile demands that we all “just come out and be open” as though that will solve everything. No, it’s not that we’re invisible. It’s that we are erased. Again and again. In so many ways and in so many contexts. And this erasure has real impacts on our lives. The bisexual community, and I include all non-monosexual folks in this umbrella even though we do not have real data on how this works out, is at risk, and our needs are not being met.

To quote Shiri Eisner in their post from earlier today, “We are literally dying. We are the largest group within the LGBT community, and the most vulnerable one among LGBs, with the highest rates of exposure to violence, sexual violence, bullying, poor health and mental health, suicidality, and poverty. We are the also the least talked about and the group most perceived as privileged dispite being at the top of every depressing statistic.”

This is important. Visibility is important! And not just visibility, but also action. We need help. We need community. Dulcinea, a bisexual trans woman, said, “[We need to listen] to people who are excluded – trans people, people of colour, disabled people, both visibly and invisibly – we have to listen, and then we have to figure out a path to more forward together and then we have to be willing to stick to our guns. Because queer communities, just like any community, are willing to cut people off and we need to stop. The world is aligning more and more against us, and we need to become a community. An actual community. Not just a space where we get to feel good about ourselves, but a space that includes everyone. That means we have to change things. We have to be willing to. That sucks and it’s hard, but I don’t think being on the queer spectrum has ever been easy, so we just have to do it.”

We need to center the vulnerable and the marginalized. The non-monosexual community is vulnerable, and is marginalized, in both gay/lesbian and straight spaces. And within our community there are others who are multiply marginalized. Our responses to these challenges need to be robust, meaningful, intentional. Visibility is one part of the solution.

The Bisexual Report came out in the UK in 2012, and was similarly important to understanding issues of bisexuality (and included discussion of the intersections with bisexual community, including race, gender, class, relationship status, ability, and others.

Despite these two critical reports, and Eisner’s phenomenal book, and so many other powerful works of visibility, celebration, resistance, and advocacy from within the bisexual community, we remain marginalized even in many queer spaces. When we are visible, when there is queer representation, it often comes with a “but we don’t need a label” overlay, which serves to further invisibilize and marginalize us.

A glossary-of-terms post on Bisexual.org has this to say about “Anything But Bisexual”:

The ABB phenomenon is problematic for the bisexual community because its use creates a vicious cycle that makes bisexuality invisible, which leads to few role models, which leads to mental health problems, and in turn fewer people willing to embrace a bisexual identity. At the same time though, it is recognized that everyone has the right to self-identify, and the bisexual community, while recognizing that ABB terms are problematic, finds it abhorrent to shame or “police” others for their self-identification. The consensus is mainly to work hard to fight biphobia and promote bi-pride, so it’s easier for more people to embrace the term bisexual.

Stereotypes about the non-monosexual community are still prevalent, and many of these stereotypes have to do with our supposed confusion, or our predatory sexualities, or our untrustworthiness and unreliability.

Linds, a Chinese American/femme/bisexual, said, “I wish people knew that being bisexual means you get stereotyped a lot as being some deviant overly sexual creature.”

Dulcinea said, “I feel like any sort of non-monosexual identity isn’t something to be ashamed of, it isn’t a threat to anyone, it’s not dangerous or predatory, I think it’s really important that we, as hard as it is, continue to strive for visibility and acknowledgement.”

These stereotypes are painful, and they also invite the community into a kind of self-policing that can throw so many of us under the bus. The stereotype that all bisexual folks are “deviant” and “overly sexual” or “predatory” harms a lot of folks, but there are slutty bisexual folks, too! And that’s great! Being sexual is okay. The slut-shaming that can happen when we try to distance ourselves from harmful stereotypes is just passing the harm on down the line, and it often lands on people who are already more marginalized. For example, accessing a “sexually pure” image is something that has been denied to Black and Indigenous women for generations, and when this racist hypersexualization is compounded with biphobic views, it can leave queer Black and Indigenous women with no space to breathe, to just be themselves, to be sexual in the ways that feel right for them. And the image of the predatory bisexual compounds with racist stereotypes about the predatory sexuality of Black and Indigenous men, meaning that they, also, are at greater risk when bisexual communities try to distance ourselves from harmful stereotypes by disavowing the behaviour rather than challenging the belief. (What I mean by that is, when we try to be “pure” rather than challenging the idea of “purity” itself.)

There are kinky bisexuals, and vanilla ones. Bisexual folks who have a lot of sex, and those who don’t. When stereotypes are used to invalidate or marginalize us, it can be tempting to try and distance ourselves from any behaviour that fits within the stereotype, but that means cutting off so many parts of our communities. We need to do better than that.

The UK’s Bisexual Index offers this poem about bisexuality:

Some people say we are confused

Some people say we are confused, because they don’t understand us

But we’re not confused

Or confusing

Some people are only attracted to one gender, and assume everyone else is just like them. That’s a mistake – a lot of people may be like that

But not bisexuals!

We’re attracted to more than one gender

It doesn’t matter how attracted

It doesn’t matter how many more genders

It doesn’t matter who we’ve dated

Bisexuality isn’t about being indecisive, or cool, or greedy. It’s simply this: attraction to more than one gender

BISEXUALITY

This fits with the framing used by one of my role models for bisexual advocacy, Patrick Richards Fink, writer at Eponymous Fliponymous. He speaks about the label “Bisexuality” as a broad umbrella term for people who are attracted to multiple genders. Within this broad label of bisexuality there are infinite variations on what that attraction to multiple genders might mean. Bi is the umbrella, and all the other non-monosexual identities can be sheltered under it. This is similar to what happens with Gay as an umbrella term that includes Bears, for example. This makes sense to me, but because the sharp division between bisexuality and pansexuality has been enforced by so many people for so long, I use “Bi+.” I also use “Bi+” because I think that asexuality, since it is not about attraction to multiple genders, but rather attraction to no genders, is different enough to warrant noting, but similar enough (because they also do not fit the monosexual norm) to warrant including.

I launched Possibilities Calgary in 2010. It was the term project in a feminist praxis course in my undergrad (I did finally make it to post-secondary!), and I was so thankful to have the support of my professor in choosing that project. My goal was to create for myself and others what I had been searching for an not found previously. I wanted a space that could act as a small antidote to the poisonous self-doubt that can creep in over time for those of us who are constantly erased in other contexts.

Now, eight years later, Possibilities is still here, and still trying to accomplish this goal.

I am conscious now of other erasures.

I see how Indigenous queerness is also erased, ignored, dismissed. Black and brown queerness, too. Immigrant queerness. These erasures all intersect with racism and xenophobia, both of which are rampant in queer spaces. So is ableism. Transantagonism. Classism and sizeism. Ageism (where are our elders? Why don’t we see them at events?)

I see the way that the asexual community is erased, dismissed, their self-knowledge invalidated by hostile suggestions that they “just haven’t found the right person yet.”

I see the way the pansexual community is also both erased under monosexual normativity (that idea that attraction to a single gender is the norm and is preferred) and also how pansexuality is used to further erase bisexuality by promoting the idea that bisexuality is inherently trans-exclusionary. This wedge, constantly driven between two parts of our non-monosexual community, is painful to watch and to experience.

Speaking about this split, Dulcinea, a bisexual trans woman said:

I find the bisexual vs. pansexual debates incredibly alienating and very unsettling. Because fundamentally, I do not see what the problem is with someone choosing any of the labels within the subgroup. It doesn’t take away from anyone else, as long as we’re not trying to force anyone else to identify this way. My being bi doesn’t take away from my partner’s pansexuality. I love and celebrate him for all the ways he feels. It feels like nonsensical fighting… The metaphor I use when I am asked why I don’t identify as pan or what-have-you, is that it’s like trying on clothes, and you have a bunch of things that fit, but then you find the right pair of jeans for your body, and it’s like, I could wear these other ones and it’d been fine, but I’d just rather wear the pair of jeans that feel comfortable, and I know I’m going to wear them in really easy, and they make my butt look good.

Rhiannon, a pansexual trans woman, said:

I was struggling as a transgender woman in the bi community. I found a lot of bisexual people that I encountered preferred binary gendered people. I was feeling very frustrated so a friend told me about Pansexuality and how pansexual people are open to all gender varieties. There seems to be this misconception that Pansexual people are against the Bisexual community for not being open to non-binary genders. I obviously can’t speak for everyone but this is not the case with the Pansexual people that I know. I acknowledge that there are many Bisexual people who are attracted to Non-Binary or Transgender people, like myself, but I felt it removed any confusion if I identified as Pan rather than Bi. To me that is what is at the core of Pansexual Identity, it is a way of letting people know immediately that you are open to all Gender Variations. We love our Bisexual Brethren, we just choose a different identify for ourselves.

And it’s important to keep in mind that just because bisexuality doesn’t inherently erase non-binary folks, or imply a lack of interest in trans folks, that doesn’t mean that there aren’t specific bisexual people who do. I was speaking with someone recently about bisexuality, and that person’s definition of bisexuality does not include attraction to transgender people. There are also lots of folks who do still speak about “both” genders, and bisexuality as an experience of attraction to “same and opposite” genders, language that erases non-binary identities (like my own!)

That’s not how I experience my own bisexuality, and that’s not inherent to bisexuality as an identity, but it hightlights how Rhiannon’s experience is valid and real. The “jeans” that fit Rhiannon are not the same “jeans” that fit Dulcinea or myself, and that’s informed by her lived experiences. There has to be space for that within our community, or else we will just perpetuate more harm.

We can (and should) talk about how the idea that you can just “have a preference not to date trans people” is inherently transantagonistic, just like having racial dating preferences is inherently racist, and we also need to validate the experiences of folks who have been excluded in these ways. We can talk about the problem, but we need to make sure that we are centring the experiences of folks who are actually suffering because of it. As Latin-Australian sociologist Dr Zuleyka Zevallos says in the second link, says, “[T]he fact is, as soon as you start to exclude people, then you’re participating in the broader pattern of exclusion that people from minority backgrounds face. That’s what people from White backgrounds don’t understand – that “I don’t have a preference towards X, Y, and Z groups,” they are contributing to the daily experiences of racism that those groups already face at work, at school, when they’re walking down the street. So this is just another form of discrimination that minorities are facing that White people don’t have to deal with.” The same is true regarding cis and transgender experiences.

One thing I really appreciated about both of the comments from Rhiannon and Dulcinea is the intentional inclusion of other identities even while strongly identifying with a specific label.

I want more of that – inclusion that holds space for difference. And in order to get that, we need visibility. We need to be able to see ourselves and to see each other.

Rachel, a cis biromantic asexual, speaking about ace-inclusion, highlighted that difference. She said:

Other than just the basic awareness that asexual people exist, the biggest mistake I encounter among people who are trying but not necessarily succeeding to be ace-friendly is that they don’t translate that into awareness that ace people’s experiences of attraction and romance are actually meaningfully different than non-ace people’s. Which sometimes leads to this usually well-intentioned but kind of awkward and inaccurate perception that aces are just their romantic orientation, but G-rated… I find that people attempting to be welcoming of ace identities tend to over-emphasize language, while I’d rather people put their effort into not assuming that allosexual (non-asexual) experiences are universal. Ace experiences aren’t intuitive to most non-ace people, and I understand that – there’s plenty of non-ace experiences I find extremely counter-intuitive – so not making those assumptions takes a lot of work, and I understand that and it’s okay to be confused by things that are confusing. But I’ve had several experiences in spaces that claimed to be (and seemed to be making a good faith effort to be) ace-friendly where they’d use all the laboriously correct language and then have discussions where it was assumed that all primary relationships were inevitably sexual, or that consent to sex that isn’t driven by sexual attraction/desire in the moment couldn’t be genuine, because they were so focused on inclusive language they just hadn’t thought about anything else.

What Rachel highlights is how we need to think broadly about our efforts towards visibility. It can’t just be language. And it can’t just be “coming out”, either. We need the kind of visibility that challenges systems of exclusion and marginalization, and we also need this visibility to happen in ways that don’t shame folks for “not being visible” – we need to take away this pressure that currently exists towards the non-monosexual community to “come out for the good of the community.”

I am not entirely sure how we will do this. I know that my own efforts exist within a rich history of bisexual activism and advocacy, and I hope that in this coming year, I can learn more about how to do this work.

Today, I’m hosting the Bi+ Visibility Event and putting up this blog post. Next year, who knows?! I have big dreams, and now that I’m dipping my toe back into event organizing (once I hit publish on this, I’m flying out the door to do final prep for the Bi+ Visibility Day panel, open-mic, and info-session today!), maybe we’ll come up with something spectacular.

In the meantime, I would love to hear your stories.

And if you’re struggling and need professional support, I would love to work with you in either my role as a narrative therapist, or as a community organizer.

Asexuality. (This interview was over email.)

There is so much variety within the non-monosexual community. How do you identify?

I identify as a cis biromantic asexual, but day-to-day I usually just say ace, because it’s the thing that comes up the most, and I very rarely see the need to give the full explanation. Usually I only bother to clarify my romantic orientation when I have a specific reason to. This is mostly internally driven, I’m fairly private by nature, it’s not that I’ve felt external pressure to do that.

How did you learn about your identity? Did you see representations of people like you?

This is a tremendously embarrassing story because I found a link to AVEN from TVtropes, and that was the first time I encountered asexuality as an identity term, which was in my early twenties. Prior to that there were a handful of characters I found which seemed to share the experiences of romance, and of lack of sexual interest that I had, but none of them were described specifically as asexual.

What do you wish more people knew about people who share your identity?

Other than just the basic awareness that asexual people exist, the biggest mistake I encounter among people who are trying but not necessarily succeeding to be ace-friendly is that they don’t translate that into awareness that ace people’s experiences of attraction and romance are actually meaningfully different than non-ace people’s. Which sometimes leads to this usually well-intentioned but kind of awkward and inaccurate perception that aces are just their romantic orientation, but G-rated. And there are people who identify strongly with their romantic orientations, but they’re a distinct minority. Romantic orientations are not even universally used.

What misconceptions do you encounter from people?

Mostly I encounter people who just have no idea that being asexual is even a possibility. Beyond that there’s also a degree of conflation of asexuality and aromanticism, which are of course, separate and orthogonal. And again there is a massive overemphasis on romantic orientation by non-ace people talking about ace people, as compared to how ace people, in my experience, talk about it, as more of a handy point of reference.

What can people do to be more inclusive of non-monosexual folks in general, and of people of your specific identity?

I find that people attempting to be welcoming of ace identities tend to over-emphasize language, while I’d rather people put their effort into not assuming that allosexual (non-asexual) experiences are universal. Ace experiences aren’t intuitive to most non-ace people, and I understand that – there’s plenty of non-ace experiences I find extremely counter-intuitive – so not making those assumptions takes a lot of work, and I understand that and it’s okay to be confused by things that are confusing. But I’ve had several experiences in spaces that claimed to be (and seemed to be making a good faith effort to be) ace-friendly where they’d use all the laboriously correct language and then have discussions where it was assumed that all primary relationships were inevitably sexual, or that consent to sex that isn’t driven by sexual attraction/desire in the moment couldn’t be genuine, because they were so focused on inclusive language they just hadn’t thought about anything else. And, also, being scrupulous about ace friendly language requires a lot of both moment to moment self-correction, and often longer more complex sentences, and that can be an accessibility issue for some disabilities or for people speaking in a second language. It’s nice when people remember to verbally acknowledge ace people (by saying for instance, things like “sexual attraction is important to those who experience it”, rather than just “sexual attraction is important”), but it’s much easier to correct and just be understanding of the occasional language slip-up, than it is to try and decide if it’s worth the energy to redirect a whole line of thought.

Are there any resources, books, articles, tv shows, movies, video games, or other pieces of representation that you would like to recommend?

If you’re looking for 101 level resources about asexuality the AVEN FAQs remain a good place to start. The online ace community has got a lot more distributed but if you’re looking for more complexity and detail than the basics I like the blog The Asexual Agenda. The book Every Heart a Doorway by Seanan McGuire is probably my go-to for being a nuanced, but also accessible, representation of an asexual character.

Is there anything else you want included in the blog post?

Not that I’ve been able to think of, although, knowing me, I’ll come up with something just after the post is published.

You were involved with Possibilities from very early on, and you brought a new perspective to the conversations. I really appreciated that, and I wonder what that experience was like for you, to be in a bisexual and pansexual space, bringing something else to the table?