Recognizing BPD Superpowers

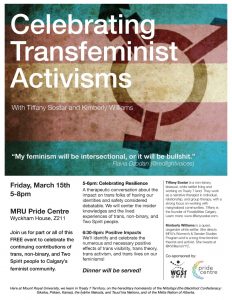

The following is a slightly modified version of the text of a presentation given on August 24, 2019. The second part of this event was an interview with Kay and Sam, which will be shared next week. Both of these posts are shared in celebration of BPD Awareness Month. The image is a still from the presentation., with Kay on the left, Tiffany in the middle, and Sam on the right.

Introduction

Welcome to “Recognizing BPD Superpowers”, on the topic of sharing and celebrating the hopes, skills, insider knowledges, and experiences of folks who identify with Borderline Personality Disorder, or BPD. This includes people who have claimed the label for themselves, people who have had the label applied to them, and people for whom both are true.

I want to note up front that this presentation will include references to self-harm, suicidality, and to some of the stigmatizing and pathologizing language that is often applied to folks who are identified with BPD. This has the potential to be triggering. If, at any point, you need to take a break – that is a-okay! Also, it’s a long post! Sorry!

Before we get started, I’d like to introduce you to my co-facilitators.

Kay D’Odorico is a queer, neurodivergent human of Indigenous and European descent. They advocate for Sex Workers and own and operate their own perfuming business full-time here in Mohkinstsís.

Sam is just a human pursuing her best possible self. She is passionate about her recovery, her intersections, and wishes to hold space for others while creating it for herself.

Both of these humans have been phenomenal supports and collaborators, and I’m honoured to have shared this space with them. The narrative interview with these two lovely humans, which followed this presentation, will be shared next week on this blog.

My name is Tiffany Sostar. My pronouns are they/them. I’m a narrative therapist, community organizer, editor, writer, workshop facilitator, and tarot reader – I do a bunch of different things, and they all sort of orient around engaging with stories. The stories people tell about ourselves and others, the stories we’ve been told about ourselves and others, and, especially, how we can tell our stories in ways that make us stronger. That phrase – telling our stories in ways that make us stronger – comes from Auntie Barbara Wingard, an Australian Aboriginal narrative therapist who has done profoundly meaningful work on many topics, including creating ways for Indigenous communities to grieve together in ways that are consistent with their cultures.

My own work is significantly influenced by the work of Indigenous narrative therapists and community organizers, including Auntie Barb, Tileah Drahm-Butler who is another Australian narrative therapist, and Michelle Robinson, who is a community organizer and politician here in Calgary. (You can find one of Aunty Barb’s projects, a walking history tour here, and one of Tileah’s project, a presentation on decolonizing identity stories here, and Michelle Robinson’s Patreon and podcast here.)

Colonial Violence and BPD

As a white settler who works in the field of mental health, a field that has historically been incredibly harmful to marginalized communities, including Indigenous, Black, trans, queer, two-spirit, fat, unhoused, sex working, substance using, and so many other communities who have come to professionals for help and been met with stigma and harm, I think that recognizing how much I have benefitted from the work of marginalized communities is critical. Any good work that I do in communities that are more or differently marginalized than I am myself is entirely due to the generosity and wisdom of the people within those communities who have shared their insider knowledges.

This workshop happened on Indigenous land, and this blog post is being written on Indigenous land. All land is Indigenous land. Here, I am on Treaty 7 land. It is the land of the Blackfoot Confederacy, including the Kainai, Siksika, and Piikani First Nations, and the Stoney Nakoda, including the Chiniki, Bearspaw, and Wesley First Nations, the Tsuut’ina, the Metis Nation of Alberta, Region 3, and all of the other Indigenous men, women, and two-spirit folks who are here as a result of child removals, forced relocations, economic pressures, or other reasons.

This work was inspired by Osden Nault, and we had been talking about getting this project underway for quite some time. We both noted the lack of BPD voices in resources and writing about BPD, and wanted to do something to address that. This presentation, and the resources that are currently under development, would not have happened without Osden. They also co-facilitated the first group discussion that created the foundation for this workshop. Osden is an artist of Michif and mixed European descent, whose art practice and research are both grounded in queer, feminist, and Indigenous world-views. Osden lives in Tkaronto on the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee, Wendat, and Mississaugas of the Credit First Nations, under the Dish with One Spoon Wampum Belt Covenant, which precedes colonial treaties on this land. Even though they weren’t at this workshop, their influence was present!

This presentation was, and is, part of a larger series of resources that the BPD Superpowers group is creating around BPD, some of which will be shared during BPD Awareness Month in May of 2020. If you live in a colonial country and don’t know whose land you’re on, it would be worth looking that up. The land you’re on is now part of this project, too.

Here in Canada, the Final Report on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA people found that:

“The significant, persistent, and deliberate pattern of systemic racial and gendered human rights and Indigenous rights violations and abuses – perpetuated historically and maintained today by the Canadian state, designed to displace Indigenous Peoples from their land, social structures, and governance and to eradicate their existence as Nations, communities, families, and individuals – is the cause of the disappearances, murders, and violence experienced by Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA people, and is genocide. This colonialism, discrimination, and genocide explains the high rates of violence against Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA people.”

Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls

We must talk about colonial violence when we are talking about trauma-related mental health experiences, which many people experience BPD as being, because otherwise we risk perpetuating harm. For example, the 2014 research paper “Characteristics of borderline personality disorder in a community sample,” published in the Journal of Personality Disorders, finds that Native American and African American communities are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with BPD, and with other conditions such as depression, anxiety, etc.

I think that, knowing this, we must look at racial trauma, and acknowledge how racial trauma impacts individuals if we are going to talk about these experiences and diagnoses. Otherwise, we are missing key context.

Rebecca Lester, in her paper, “Lessons from the Borderline” writes:

“Most people diagnosed with BPD grew up in situations where their very existence as a person with independent thoughts and feelings was invalidated (Minzenberg et al., 2003). Sometimes, this entailed chronic abuse, either physical or sexual. Sometimes it was more of a grinding parental indifference. People diagnosed with BPD overwhelmingly experienced their early lives as involving constant messages that they do not – and should not – fully exist.”

Lester, Rebecca J. (2013) “Lessons from the Borderline: Anthropology, Psychiatry, and the Risks of Being Human.” Feminism & Psychology, 23(1): 70-77.

How can we separate this from the findings of the Final Report, which identify exactly this dynamic of abuse and identity invalidation as having been directed at Indigenous communities since the beginning of colonization? I don’t think that we can.

What even is a “personality disorder”?!

So, borderline personality disorder, like many “personality disorders” is a contested and controversial term and diagnosis. Heads up for some stigmatizing and pathologizing language in this next section. I want to give you a bit of context for the social location of BPD, and for my own positioning here.

I have never received a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. Although there are many BPD characteristics that I do strongly identify with, and I share an experience of trauma that many BPD folks might recognize, I do not feel a strong attachment to the BPD label. In my own life, I am comfortable recognizing certain shared experiences without claiming a shared identity.

In my own work, I do not diagnose the community members who consult with me for narrative therapy, but I do respect and work with the diagnoses that people bring into our sessions. There are lots of reasons for this, but one important one for locating myself within this work is that as a narrative therapist, I am interested in externalizing problems – meaning, locating the problem outside of the person I am consulting with. I think that many contemporary ways of speaking about borderline personality disorder invite us to view BPD as a set of traits inherent to an individual.

BPD is often described as a volatility that can make people dangerous, an instability, a lack of cohesive identity – all of these ways of speaking about BPD locate it within the person, rather than within their context. I think that this obscures the many ways in which folks who have been identified with BPD respond to the problems in their lives. These ways of speaking, of telling a story about BPD, can end up having the consequence of giving BPD more agency than the person in front of us!

And I think that this is a problem.

I also think it’s a problem that can arise even when we’re not being malicious or trying to be stigmatizing – “You can’t help it, it’s the BPD” is a framing that invites neither accountability nor dignity and agency, even though it appears to be a compassionate approach.

Instead, I am interested in how people respond when BPD shows up in their lives. I’m interested in learning when this problem first showed up, what it wants, and how people have responded to it. What are they valuing when they pick up a DBT workbook and start developing their strategies for emotional regulation? What are they hoping for when they continue to show up in relationships despite the BPD voice telling them to bail? Who taught them that they could respond? Who in their lives knows what they cherish, and would not be surprised to learn that they are taking actions to respond to the problems in their lives?

Rebecca Lester writes:

“I understand BPD somewhat differently than my clinical colleagues who see it as a dysfunction of personality and my academic colleagues who see it as a mechanism of social regulation. In my view, BPD does not reside within the individual person; a person stranded alone on a desert island cannot have BPD. Nor does it reside within diagnostic taxa; if we eliminated BPD from the DSM, people would still struggle with the cluster of issues captured in the diagnosis. Rather, BPD resides – and only resides – in relationship. BPD is a disorder of relationship, not of personality. And it is only a ‘disorder’ because it extends an entirely adaptive skill set into contexts where those skills are less adaptive and may cause a great deal of difficulty. Yet due to the contexts in which the skills were developed, the person has a great deal of trouble amending them (Linehan, 1993). Since BPD resides in relationship, BPD can also be attenuated through relationship: it is not a life-sentence, and it is not even necessarily problematic if managed constructively.”

Lester, Rebecca J. (2013) “Lessons from the Borderline: Anthropology, Psychiatry, and the Risks of Being Human.” Feminism & Psychology, 23(1): 70-77.

One of the foundational beliefs of narrative therapy is that the person is not the problem, the problem is the problem, and the solution is rarely individual. I think that this is an important framing to bring to discussions of BPD.

So that’s where I stand.

Questioning the Discourse

How about the discourse around BPD?

In her fantasy book Borderline, author Mishell Baker, who identifies as BPD herself and has written a badass BPD heroine for the novel, writes, “Sometimes, the first thing people learn about borderlines is that you can’t trust them. And there’s not always much learning after that.”

That’s why it is so important to think critically about the stories we are telling about BPD, and about people who are identified with BPD. To keep learning. To interrogate what we have been taught or told about what it means to live with BPD experiences.

Does the story leave room for the dignity and agency of the person being described?

Does it position the person as the expert in their own experience?

Who does this story serve, and what are the potential outcomes of this story?

We need to ask these questions anytime we read an article, a post, a book, a webpage – what, and who, is being supported in this narrative?

What, and who, is being diminished?

Bring these questions with you anytime you engage with writing or speaking about BPD (or anything else!)

BPD is recognized as one of ten personality disorders in the DSM, The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. In the ICD-10, the manual used by the World Health Organization, this diagnosis is named “emotionally unstable personality disorder.”

The Mayo Clinic defines a personality disorder as:

“A type of mental disorder in which you have a rigid and unhealthy pattern of thinking, functioning and behaving. A person with a personality disorder has trouble perceiving and relating to situations and people. This causes significant problems and limitations in relationships, social activities, work and school.”

Mayo Clinic, Personality Disorders

We’re going to come back to this idea of “trouble perceiving and relating to situations and people” because, in fact, many participants in our BPD Superpowers group identified themselves as being uniquely and specifically skilled in observing their environments, relationships, and selves, and in building community and empathizing and connecting with other people. Although it is true that many folks experience BPD as getting in the way of their relationships at times, this does not mean that they cannot perceive and understand what is happening around them.

BPD and Abuse

This framing, this story of what a personality disorder is, can be weaponized against a person who is identified with BPD. It can actually leave them more vulnerable to abuse, because it frames them as being somehow inherently and perpetually incapable of accurate perception. Even if this is not what a clinician might mean when they use this language, this is what you get from a quick google search. Very little discussion of the social contexts within which these so-called “personality disorders” arise, and almost nothing that describes the skillful and intentional ways in which people respond to these problems.

Gaslighting refers to actions that cause someone to question their own memory, perception, or sanity. Gaslighting can happen intentionally – lying about, denying, or misrepresenting what has happened.

But it can also happen unintentionally when we treat someone’s perception as unreliable, when we default to the idea that they are lying or mistaken, when we refuse to position them as the experts in their own experiences. The discourse of personality disorders as meaning that a person “has trouble perceiving situations” can create a context within which a person with BPD is being constantly, and often unintentionally and non-maliciously but still harmfully!, gaslit. It can leave people who are identified with BPD in the position of not being believed if they are subjected to abuse. It is not a helpful framing.

How are we witnessing BPD?

As an alternative framing, it might be helpful to ask ourselves what is influencing how we are witnessing the people in our lives who are identified with BPD. Are we kind witnesses to their experiences? Are we holding space for them to share their insider knowledges into what they need, what they are experiencing, and what is helpful for them?

And on the topic of helpful or unhelpful, here is what Wikipedia has to say about BPD:

“BPD is characterized by the following signs and symptoms:

- Markedly disturbed sense of identity

- Frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment and extreme reactions

- Splitting (“black-and-white” thinking)

- Impulsivity and impulsive or dangerous behaviors (e.g., spending, sex, substance abuse, reckless driving, binge eating)

- Intense or uncontrollable emotional reactions that often seem disproportionate to the event or situation

- Unstable and chaotic interpersonal relationships

- Self-damaging behavior

- Distorted self-image

- Dissociation

- Frequently accompanied by depression, anxiety, anger, substance abuse, or rage

The most distinguishing symptoms of BPD are marked sensitivity to rejection or criticism, and intense fear of possible abandonment. Overall, the features of BPD include unusually intense sensitivity in relationships with others, difficulty regulating emotions, and impulsivity. Other symptoms may include feeling unsure of one’s personal identity, morals, and values; having paranoid thoughts when feeling stressed; depersonalization; and, in moderate to severe cases, stress-induced breaks with reality or psychotic episodes.”

Wikipedia

The wiki page also includes the Millon subtypes, which include Discouraged borderline, Petulant borderline, Impulsive borderline, and Self-destructive borderline. Fabulous.

So that’s Wikipedia, which is one of the first places that many folks look when they receive a diagnosis of BPD or when they are trusted with a disclosure from a friend or family member, or when they hear about someone having BPD.

If you are here as a friend, family member, or someone in community with folks who are identified with BPD, imagine what it might feel like to read that about yourself, and to have that be the dominant narrative of who you are. Imagine what it might feel like to know that people around you are reading this about you, and may be talking about you and people like you in these terms.

If you are here as a person who identifies with BPD, know that I and every one of the people involved in this project, and many people beyond this group, see you for more than these degrading and diminishing descriptors. We recognize your superpowers. We recognize your resilience. In one of the group discussions, a participant said, “Every single person with BPD who is still with us, and those that aren’t still with us, I think that we absolutely deserve to be acknowledged and that our hard work should be acknowledged. Not tokenized or pedestalized, but having that work acknowledged and witnessed.”

I agree.

And I agree with Rebecca Lester when she writes:

Through challenging embedded bias, honoring the testimonies of individuals, questioning of our own motivations, and renewing a commitment to reduce injustice, silencing, and suffering, our intellectual, clinical, and human potentialities are being stretched and, if we are fortunate, will continue to grow.

What I find most compelling about my clients with ‘borderline’ symptoms is that they are still struggling to exist despite the deep conviction that they do not deserve to do so. And they are still struggling to connect with others, despite being told again and again that they are manipulative and controlling and difficult. Far from being inauthentic, then, these individuals are reaching out into the world in the most honest, direct, vulnerable ways they possibly can, all the while bracing for the invalidation and hostility that they know is likely to follow. They cannot help but reach for connection, and to hold out faith, however dim, that they will find it. I find this incredibly inspiring; it puts front-and-center the impulse for growth and health that I believe exists in all of us, no matter how encrusted with despair, dysfunction, hopelessness, or defeat.

I learn from these clients every single day. Their struggles and their resilience humble me. They remind me that intellectual critique is but one piece of a much larger puzzle, and that they have experiences that deserve to be heard and validated, even when (perhaps especially when) they challenge our interpretations. They push me to become a better scholar, a better clinician, and, I hope, in the end, a better human being.

Lester, Rebecca J. (2013) “Lessons from the Borderline: Anthropology, Psychiatry, and the Risks of Being Human.” Feminism & Psychology, 23(1): 70-77.

One of the contributors to the BPD Superpowers project, D. Ayala, shared the following on her facebook page and has given us permission to use this quote in the resource.

with my bpd symptoms, I just can’t handle cbt or dbt thanks to fucked up experiences in the past. And I don’t trust any therapists bc they’re only getting my POV about what’s happening and I think they side with me more than is valid sometimes. And also trusting someone else’s judgement more than my own is so damaging as an abuse survivor.

but I notice my reactions getting less and less severe over the years and that’s just like a combination of introspection, community, and also others holding me accountable. Plus realizing I have bpd helped me be able to recognize when I’m having a flare and prepare accordingly.

basically, mental health care can look really different for different ppl. I feel like my doctors act like I’m resisting treatment when really I’m just resisting being harmed more.

D. Ayala, Facebook post

Difficulty in relationships is one of the most common traits associated with BPD, and yet our group has maintained such a strong focus on community and the role of cherished friends and community members. This group, and so many folks identified with BPD beyond this group, prove how thin and simplistic are the dominant narratives of BPD.

I’m going to end with the list of superpowers that were identified in our group conversations. These superpowers will be explored more fully in the collective document, which I hope to have ready to share by the end of this month!

THE SUPERPOWERS

- The Superpower of Community (and community care)

- The Superpower of Showing Up

- Resilience

- Endurance

- Dialectics as a Superpower (holding multiple true stories)

- Empathy and Compassion

- The Superpower of Quick Turnaround of Emotions

- The Superpower of Being Able to Get Out of a Bad Situation

- The Ability to ‘Chameleon’

Check back next week for the next BPD Awareness Month post, which will be the video and transcript of the interview with Kay and Sam.