by Tiffany | Feb 20, 2019 | Gender, Health, Intersectionality, Narrative therapy practices, Relationships, Woo

(This post was originally written for my tarot blog.)

I am tired of watching the people in my life suffer at the hands and words of people who claim to love them.

And it does not escape my notice that it is more often the femmes, the women, the disabled, the neurodivergent, the vulnerable who are experiencing violence and abuse from their partners.

I am overwhelmed with listening to people who consult me for narrative therapy, and who consult me as a friend, talk about what has been done to them, talk about what has been said to them, talk about what has been said about them, and to hear them questioning themselves with the oppressive voices of our culture.

Was it really so bad?

He didn’t mean it.

Am I too needy?

He was drinking.

They were having a panic attack.

Everything I say makes her angry.

He really tries.

Maybe it’s not so bad.

Maybe it’s not so bad.

Of course they doubt themselves! Our culture chronically gaslights marginalized communities. Marginalized communities are often operating within transgenerational trauma, poverty, scarcity (if not in our families, then in our communities). Marginalized communities may also have to contend with other structural and systemic issues that make naming abuse and violence more challenging – Black and Indigenous communities are at such increased risk of violence from any system. Seeking help often means finding more violence.

There is so much normalization of violence in our culture. And although it is not an issue that only impacts women, or is only perpetuated by men, there are patterns. They are painful patterns to witness.

One of my friends recently posted this open letter to men:

Dear men,

Just wanted to let you know I am so over it. I talk to your partners every day. I see their tears and listen to their self flagellation in the effort to make you happy. I watch them cram themselves in tiny boxes so they don’t threaten you. I fume as they suggest, gently, kindly, if it’s not too much trouble, that you consider their needs, but your wants are more important. Men, I watch you casually ask for sacrifice as if it were your due. I seethe as your partners ask for the simplest things of you, and you just don’t even bother. I see you go through the motions and call it love, when it doesn’t even pass the bar for respect. And then, as it all falls apart you claim you need a chance, as if you haven’t been given dozens, that you didn’t know, as if you hadn’t been told relentlessly, and that you can change, as long as you won’t be held accountable.

Men, I am so over watching your partners unilaterally trying to fix relationship problems that are yours. I am tired of knowing your partners better than you. I am exhausted having to buoy them through the hard times because you cannot be bothered. I am tired of you cheapening what love means by buying the first box of chocolates you see (not even their favourite) and calling it an apology but changing nothing.

Don’t hurt my people. Men, do better or go home.

And still, the questioning. Maybe it wasn’t so bad? Maybe it wasn’t so bad. Maybe it wasn’t so bad. Because each incident on its own might not be so bad. Might be a bad day, a bad choice. Might be a bad moment. It’s not the whole story. Maybe it’s not so bad.

And on its own, maybe it isn’t.

Image description: The Ten of Swords from the Next World Tarot.

From the guidebook by Cristy C. Road:

This is the final straw, and the 10 of Swords is exhausted from counting. They have lost themselves, over and over, in the name of love, self-worth, trauma, post-traumatic stress, healing the body from abuse, healing the mind from manipulation, and unwarranted, non-stop loss. The 10 knows healing, they studies it and have been offered power, candles, bracelets, and messages from their ancestors through local prophets who run their favorite Botanica. They are listening, but they are stuck. Proving to their community that while they have known power, they have known pain they don’t deserve.

The 10 of Swords asks you to trust your pain, own your suffering, and don’t deny yourself of the care you deserve from self, and the validation from your community. That validation is the root of safety. The 10 of Swords believes now is the time to ask your people for safety.

I pulled this card after another conversation with a beloved member of my community about an incident of misogyny in an intimate relationship.

I had brought this question to the deck – “How do we invite accountability into our intimate relationships?”

I wanted to know –

How do we create the context for change without putting the burden of emotional labour onto the person already experiencing trauma from the choices and behaviours of their partner?

How do we deepen the connection to values of justice, compassion, and ethical action, for people who have been recruited into acts of violence and abuse?

How do we resist creating totalizing narratives about people who use violence and abuse? How do we resist casting them as monsters? How do we invite accountability while also sustaining dignity?

How do we, to use a quote by one of my fellow narrative therapists, “thwart shame”? (Go watch Kylie Dowse’s video here!)

In moments of distress, I often turn to the tarot. When I don’t know how to ask the right questions, and I don’t know what to say or do, I turn to the tarot. Tarot cards are excellent narrative therapists.

I flipped this card over and the image moved me immediately. These acts of intimate partner violence and abuse do not occur in a vacuum. It is not just one sword in the back.

A misogynist comment from a partner, directed towards a woman or femme, joins the crowd of similar comments she, they, or he has received their entire life.

A racist comment from a partner, directed towards a racialized person, joins the pain of living an entire life surrounded by white supremacy and racism.

An ableist comment from a partner, a transantagonistic comment, a sanist or healthist or fatphobic or classist comment – these comments join the crowd.

And so, how do we invite accountability while preserving dignity? How do we resist totalizing narratives of either victims or perpetrators, resist recreating systems of harm in our responses to harm?

See the whole picture.

Even though it is so painful to look at, see the whole thing.

Rather than locating violence and abuse as problems that are localized to a relationship, individualized and internalized to a single person making choices, recognize that these things happen in context. And for many folks, these contexts are incredibly painful.

It will take time, and patience, and compassion, and gentleness, and a willingness to do the hard work of both validation and accountability. It will take community to find safety.

We need each other to say, “it is that bad, even if this incident might not be.”

When the victim-blaming, isolating, individualizing voices start clamoring, we need each other to say, “this is not your fault.”

We need something more nuanced than “leave,” “report.”

We need to show up for each other, with each other. We need safety. We need validation.

Can we do this by asking questions like:

How did you learn what it means to be in relationship?

What examples of making choices in relationships have you seen around you? What was being valued in those choices?

Does what you’ve learned about being in relationship align with what you want for yourself, and what you value for yourself?

Do the actions you’re choosing in your own relationship align with your values or hopes?

Who has supported you in your values and hopes?

Do you share any hopes or values with your partner(s)?

What have you learned about violence and abuse in relationships? About who experiences violence and abuse? About who enacts violence and abuse?

When did you learn this?

Does this learning align with what you’ve experienced in your own relationship?

What insider knowledges would you add to this learning, from your own experience?

Have you ever taken a stand against violence and abuse in your relationship?

What enabled you to take this stand?

When violence or abuse shows up in your relationship, are you able to name it? Have you ever been able to name it? What supports this ability?

What have you learned about what it means to be accountable in relationship?

Do you have supports available to you that invite accountability while sustaining dignity?

Who can support you in being accountable for the actions you’ve taken when you’ve been recruited into violence or abuse? Who can support you in asking for accountability from a partner who has been recruited into violence or abuse?

Here are some resources if you’re looking for ways to respond to intimate partner violence:

The Stop Violence Everyday project.

Critical Resistance’s The Revolution Starts at Home zine.

The Creative Interventions toolkit.

(This post was originally posted on my tarot blog. You can find it here.)

by Tiffany | Feb 17, 2019 | Intersectionality, Read Harder 2019, Writing

This is an expanded version of the review I posted to Patreon earlier this month. If you want to support my work and read early versions of many of my projects, you can join the community here!

Content note: talking about racism and white supremacy

For the first time in… I don’t even know how long!… I finished a substantial novel in a week. That novel was Esi Edugyan’s Washington Black.

There were a few factors that made it possible, and I want to acknowledge that this isn’t always possible (for me or for anyone else dealing with a notable lack of time). The most important factor was that I spent a lot of time in the passenger seats of cars, so I had a solid 10 hours to read. I also decided to devote some time on the weekend to reading, so I spent a few hours in coffee shops reading when I could have been working instead.

It meant the next week was a bit stressful, and now two weeks out from it I’m still trying to get caught up on some of the work I put off, but it was worth it.

Washington Black by Esi Edugyan was so very worth it.

If you have the chance to read this book, take it. And be prepared to be pulled into this world, which contains so much nuance and life and depth and joy and pain.

I’m working through Layla Saad’s Me and White Supremacy workbook this month, and reading Esi Edugyan’s novel, which holds a mirror up to slavery-era white supremacy, and to the white supremacy that remains in our current culture.

In this mirror, I saw my own complicity with, and cooperation with, ongoing patterns of privilege and domination. I see in myself Christopher Wilde’s self-serving white savior thoughts and actions. I see in myself, and in the context around me, so many of the harms perpetuated by well-meaning white people in the book. And I see the blatant and violence racism of the book still present in the world around me, even the world very close to me.

Washington says, “How could he have treated me so, he who congratulated himself on his belief that I was his equal? I had never been his equal. To him, perhaps, any deep acceptance of equality was impossible. He saw only those who were there to be saved, and those who did the saving.”

This is deep and relevant and contemporary knowledge. In the last two weeks I have watched a community that I was part of absolutely combust in white backlash, and I have been so moved by the discourse that invites to consider not how we can be inclusive but rather how we can challenge and stand against exclusion.

“Being inclusive” puts us in Christopher Wilde’s well-heeled shoes. It puts us on the side of “those who do the saving.” We share our spaces. We “pass the mic” (because we maintain control of the mic).

Instead, we have to accept the invitation that Black and Indigenous theorists have been saying for generations. We have to recognize that there is not “those who are there to be saved, and those who do the saving.” These hierarchies are hierarchies of harm.

The book was beautifully written, with rich and evocative metaphors. The characters were written with such care and generosity. Washington’s experiences, and his reflections on the world around him and his own place in the world, are so carefully and skillfully shared with the reader. It’s heartbreaking and heartening and absolutely gorgeous.

I was especially moved by how compassionately Edugyan treated each of the characters, no matter how misguided or actively harmful their actions may have been. There are monsters in the book, absolutely. There is no doubt that many of the white characters are deeply influenced by and actively complicit in genocidal white supremacy. But even the most monstrous of these characters is also a human, a person who has hopes, who feels love and gentleness, full of complexity and a desire to find happiness, to be seen as a good and worthy person. This makes the book infinitely more powerful, because it resists creating a simple (and therefore easily dismissed) stereotype of racist villainy. Instead, the violence and inexcusable harm is committed by people who are so much like me.

Esi Edugyan is masterful in her storytelling, and she is part of a long lineage of masterful storytelling by Black women.

I am so thankful for the generous work of Black women. For the visionary work of Afrofuturists and Black feminists. I am so thankful for the invitation to see the world with the clarity and the active hope of writers like Esi Edugyan, Nnedi Okorafor, N.K. Jemisin, Octavia Butler, adrienne maree brown, and so many others.

This is the book I read for the category of “A book by a woman and/or author of colour that won a literary award in 2018.” Washington Black won the 2018 Giller Prize (a second Giller win for her!). It was also shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize and the Rogers Writer’s Trust Fiction Prize.

You can find it here at Shelf Life Books.

You can read my other reviews for the Read Harder 2019 challenge here!

My review of Binti for “a book by a woman and/or an author of colour set in or about space.”

My review of When They Call You A Terrorist for “a book of nonviolent true crime.”

by Tiffany | Feb 14, 2019 | #tenderyear, Intersectionality, Narrative shift, Polyamory, Writing

Image description: On the left a paper heart hanging among many hearts, on the right a single torn paper heart. Text in the centre reads “it’s complicated.”

There is already so much good writing available on the topic of love, and I find myself hesitant and slow to write this post, which feels so important but feels so superfluous, redundant, pretentious. What can I say that hasn’t been said better by others?

I think that this, the stumble at the beginning of this post, is part of what and why I kept coming back to this text file again and again over the last month. Can anything new be said about love? Does it matter? Is what we want to say valuable even if it is not new? There are questions here about authenticity, originality, value and voice. Discourses of love.

So, first, I want to share some of the great writing that has inspired and moved me on the topic of love. I’m sharing these at the beginning of the post rather than the end, because within those questions of value and voice there is also the question of privilege. Whose voice am I lifting up? And many of these pieces of writing come from people who are more or differently marginalized than I am, whose voices need to be heard.

The entire seventh issue of Guts Magazine, on the topic of Love. Every piece of writing in this issue has something to offer, something liberatory and complicated. Read all of them, if you have the time. It’s worth it. From the editorial:

“Why look for The One, when what we want, what we need, is the many? The multiple? Not partners, but practices of love. Why is single (singular, alone) the opposite of the couple? Why is the alternative not an even greater plurality? Again, not only of lovers, but of life-sustaining arrangements of relations that we navigate without containment?

This issue is an attempt to locate and articulate ways of shoring up against the hurtful shape of love we’ve been handed by the state, by colonialism, by the family, by patriarchy. The artists and writers featured here are seeking a less deadly sort of love—forms of love that are not so easily weaponized against one another.

It’s about clearing and defending ground for new shapes to emerge when we see them struggling into life. This issue is looking for those nascent configurations about to come into view.”

Caleb Luna’s article, “Romantic love is killing us: Who takes care of us when we are single?” at The Body is Not An Apology.

“I don’t want to be loved. I want to be cared for and prioritized, and I want to build a world where romantic love is not a prerequisite for these investments—especially not under a current regime with such a limited potential for which bodies are lovable. Which bodies can be loved, cared for, and invested in.

It does not have to be this way. We can commit to keeping each other alive despite our sexual capital. We need to care for each other to keep each other alive. The myth of self-assurance is neoliberal victim-blaming in an attempt to obscure, neutralize and depoliticize our actions in the name of independent thoughts and actions and to skirt accountability.

Can we care for each other outside of love? Can we commit to keeping the unloved and unlovable alive? Is this a world that we have the potential to build?”

Shivani Seth’s article, “What’s next in the culture of care?” at Rest for Resistance.

“When we see our interactions and our strengths as ways to give to each other, as a flow back and forth, it’s easier to see how self-care and community care are naturally intertwined. We move the nexus of self-care to the community and spread our relative wealth out. Like a microloan or a community bank, we can take what is too small to support one individual and enlarge the potential impact by pooling our collective resources. We begin to work on trusting each other in slow, small ways.”

Samantha Marie Nock’s article, “Decrying desirability, demanding care” at Guts Magazine.

“This brings us back to the beginning: my anxiety about being abandoned. In reality, I should be calling this, my anxiety that all my friends are going to find romantic partners and leave me behind and I’m going to lose the world I’ve learned to live in. I cried recently, in a cab at 5am, because I had an anxiety attack at a party sparked by my friend showing interest in someone. I know this isn’t normal; I’m well aware, delete your comment right now. This was super embarrassing but my friend and I talked about it and I admitted why I had a melty. It has been a good and ongoing discussion and a growing opportunity. But it was the first time in my entire life that I have ever expressed this fear to someone, especially a close friend who is implicated in this anxiety. My friend is really supportive and didn’t run when I unloaded years of hurt and trauma onto the living room floor. Living in my body also means being terrified of telling anyone anything that might scare them because you don’t want to be “crazy” and fat. You already feel like you’re too difficult to love. So laying out my vulnerabilities shook me. I’m still shaken, and I’m still processing. It’s scary to straight up tell someone: “I’m scared that one day you’re not going to care for me like you do now because you’re going to do something that is completely normal and expected in our society that I can’t participate in on an equal level.” It’s scary to ask someone to rip apart the world we live in and help you create a new one where you feel safe.”

And there’s more. There’s so much amazing work being done on the topic of loving, and liberating love from oppressive discourses, demands, expectations, entitlements. People are telling their stories, and their stories are incredibly moving.

Non-orgasmic love.

Unexpectedly persistent queer love.

Decolonial love.

Please share your favourite links in the comments – I would love to read more.

Languages and/of Love and/of Loneliness

I’ve been thinking about love languages a lot lately. And I’m always thinking about stories – the stories we tell and are told, about ourselves, about each other, about what’s real, what’s valid, what’s worthy. I’ve been thinking about loneliness and the language of loneliness, lately. I’ve been thinking about connection, and collective action. Community, and communities of care.

I’ve been thinking about silence and silencing and quietness.

I’ve been thinking about love.

(I’ve been thinking about leaving Facebook and starting an email newsletter.)

I’ve been thinking about the apocalypse, and about neo-liberal fatalism. (Articulated by Paolo Freire, this is “an almost casual acceptance of ongoing social inequalities as inevitable,” and a sense that just because the solution has not been discovered, it does not exist. This is particularly prevalent among privileged progressives, and I am absolutely guilty of it, of not seeing a way forward and feeling deeply fatalistic about this. Powerful antidotes exist within Indigenous feminism, Black feminism and Afrofuturism, and in the insider knowledges and transgenerational survivance of so many oppressed peoples.)

I have been thinking, especially, about how we speak our love, hear our love, receive and transmit our love within scarcity.

I have been thinking about the loneliness of “burn-out.” I agree entirely with Vikki Reynolds critiques of the discourse of burn-out (link is to a PDF of her article, “Resisting burnout with justice-doing”). Reynolds calls out the discourse that frames burnout as an internal rather than contextual problem, and suggests that one way to resist burnout is through solidarity and collective care.

I think, yes!

And I think, how?

How?!

From October 2017 to October 2018, I participated in the Tender Year project with two of my dearest loves. We each engaged with the project in our own ways, and our ability to participate actively ebbed and flowed over the course of the year, but in that year, I felt myself to be actively in solidarity with community. The project has been over for months now, and I still miss it. I have not managed to maintain that feeling of connection.

I am lonely.

I struggle to do the work of connection and cultivating community in ways that feel nurturing to me. I do the work. I can even say, and believe, that I do the work well (sometimes, in some ways). But do I do it in ways that feel nurturing to me? That is an important question. It feels critical, actually. How do we tell stories about ourselves in loving relationship, in community, in connection, in ways that honour the prickly static that surrounds so many of us who are living in pain and under financial pressure?

How do we tell stories that honour the complexities of our experiences, that resist reducing our experiences down to totalizing narratives of connection or disconnection, love or lovelessness, hope or hopelessness? How do we hold space for this complexity? How do we find language for these contradictory and still concurrently true stories?

Because it is true that I am lonely these days. I feel this truth so often, particularly in weeks (and there are many of them) when all of my interactions are somehow related to my work.

And it is also true that I am blessed with an abundance of love in my life.

I know that I am not the only person experiencing this complexity, and feeling guilty and overwhelmed at my own emotional responses.

I feel that if it is true that I am surrounded by loving community, including: loving partnerships, some of which have survived multiple major relationship structure transitions, one of which includes co-parenting, all of which are deliciously and actively and intentionally anti-oppressive; loving platonic friendships; loving family-of-origin relationships (shout out to my amazing sister, one of the foundational relationships in my life); loving chosen family relationships; and loving extended community relationships – if this is all true, and it is, then what right do I have to feel lonely? To feel isolated? To feel stretched too thin and with support that does not meet my needs? What kind of ungrateful, entitled wretch am I?!

And the companion narrative to this self-flagellation – when will everyone realize how ungrateful I am, and abandon me? And, even more profoundly present in my life – when will everyone in my life become tired of subsisting on the little I have to offer, and abandon me?

So I feel simultaneously overwhelmed with gratitude when I think about the people and the relationships in my life, and overwhelmed with guilt for the fact that I am still struggling and the fact that I feel I often have so little to offer outside of (and even sometimes within) my work.

I rarely see my people outside of work contexts, except the ones I live with. (And even there, do I do enough work around the house? Do I tidy up enough, do I cook enough, do I do enough childcare? The uncharitable answer I provide myself is no. Absolutely not.)

I am too busy, all the time. I am achy. I am tired. I am always, always (almost always) feeling overwhelmed. I don’t get enough done. I’m barely keeping up. Yesterday, I forgot to call someone who wanted to talk about working together. A referral! Of all the things to forget. I forgot to email someone potential dates for our next narrative session. I’m behind on everything, constantly. My editing work. My freelance writing work. My own writing work, which is precious to me, and yet constantly falls away. The blog posts and zines that seem to constantly be “getting there” but never actually get there.

There is a pervasive feeling of chaos in my life, and this feeling can obscure the concurrent truth that I do actually get a lot done.

When I reread Shivani Seth’s piece before writing this post, I felt the sharpness of my longing for just a little more time, more rest. More ease. More space for more care.

My pain has been unreal this last month. Every day, it hurts. My body hurts. My head hurts. This means my heart hurts. And I question myself constantly – who am I kidding, thinking I can be a narrative therapist, thinking I can make this my life? When that means that I need it to be financially sustainable… I can’t even finish these thoughts. They trail off into the abyss.

This impacts the experience and the language of love.

When I send a message to a partner or a beloved friend or to my sister or someone else, and I say, “I love you,” I mean this with such intensity and intentionality. And when they say it back, I believe it. And also, I struggle with it.

One of my community members recently described an experience of being “immune to niceness” and another described a type of “dissociating from affection.” These descriptions resonate for me. It’s like stress and contextual pressure and fear of failure and fear of abandonment create a buffer of static around me, and the feeling of being solid in the love ends up dissipated and repelled.

But this is complicated. This story of static and fear is not a true story that exists in an absence of other true stories. There is also the true story of receiving and knowing love. I am thankful for this complexity. I am thankful for stories that do not ouroboros into a tidy bow, stories that contradict themselves. Like this story of scarcity and fear, which contradicts itself constantly.

Earlier this week, I shared the following:

I often have considerable anxieties about my narrative therapy practice.

Like, I’m not accredited as a counselling therapist and I probably won’t be unless I do another degree.

And I don’t work with an organization.

And I have a ton of community organizing experience but does that count *really*?

And I have some pretty strong political views and they absolutely are present in my narrative sessions.

And sometimes I’m a bit of a “down the rabbit hole” kind of person, and often it works out but every so often it doesn’t.

Like, these concerns come up really often for me. There have been so many times when I’ve sat in front of my computer, or stood in the shower, or been driving, and my head is just *full* of thoughts like, “what do I think I’m doing? why should anyone trust me?”

Do I actually know what I’m doing?

Am I actually making a difference?

And the stresses of living under capitalism also come into play – am I ever going to have enough business to make this sustainable? How will I develop this business without cooperating with the overwhelming whiteness of the wellness industry (because I am not willing to do that)? A lot of folks have said that I need to find the folks who can pay my full rate to subsidize the folks who can’t, and I need to aim my marketing towards that, but… that implies I know anything about how to do marketing in the first place?

And I know that narrative therapy, narrative practice, explicitly and intentionally welcomes people like me – outside of institutions and organizations, working in community, noodling along without as much formal training (or the kind of training) that is expected. But still. That anxieties are there. A lot.

But!

Anyway!

What I’m saying is!

I have these concerns pretty often and then other times I just feel so good about my practice, and I love what I do, and I love joining with my community members to co-research the problems in their lives. I just love it. And it feels like home for me. And there are times when I have a narrative conversation and I’m like, “damn. this is exactly what I want to do with my life. I am going to keep doing this, and just have some faith that it will work out.

My community showed up for me with such incredible words. Here is some of what they shared:

“As someone you have helped I want to say that you have made a difference in my life, and that what you do matters, and that you’re very good at it, and that I hope you continue doing what you do. Also, thank you.”

And someone else responded, “I couldn’t have said it better. Ditto!”

“I keep meaning to tell you that I got one of your fridge magnet in one of my event bags like last year and it’s still on my fridge so I can remind myself of the advice on it. In case you ever wonder if you are making a difference.”

“Our medical system is incredibly broken, especially when it comes to mental health and wellness. To do the amazing work you are doing, and want to keep doing, it’s probably actually part of your incredible strength and versatility that you _don’t_ go through the systems of control and conformity that characterize “accredited” mental health care. <3″

“You are a true gift to me and so many others like us.”

“Tiffany, I can confidently say that you have opened windows in my heart that I didn’t know were closed. I have referred many friends to your blog writing and Facebook page because what you say and how you say it is profoundly validating and stimulating. Keep going, you must!”

“Could some of what you frame as anxiety or self-doubts be part of your own process of self reflection? Is it a way of exploring your space/faith in yourself and shaping the balance between the more rigid spaces in healthcare and capitalism? I’m a part of the mainstream healthcare system, and I intentionally try to point out how little capitalism and the way it shapes the societal rituals and beliefs has anything to do with humanity and wellness. And part of how I measure success has to do with feeling uncomfortable in the space I’m in, and knowing that I simultaneously want to be of service to my community and also stay aware of the fundamental flaws in the system I’m a part of. When I read your words I feel like there’s a lot of similarities. I feel like your niche and your place of belonging is more focused than mine, and we’ve touched on the difference between narrative therapy and OT. I pretty much just want to give you a big hug and remind you that marketing is the word capitalism uses to frame networking and connection and building community capacity and recognizing skill and ability and specialization that doesn’t make someone better than another person. I love the scope and heart of what you do. I love your bravery and not compromising your ideals and values in order to ease your path.”

“I definitely see value in your narrative therapy practice! I could choose to go to a counselor who’s accreditation is acknowledged in Alberta and have part of the fee reimbursed by my insurance provider… But I find way more value in meeting with you. Your political stances create a space where I feel safer, as I know I am unlikely to experience queerphobia or fatphobia in that space. I could be wrong, but I’m also guessing that working outside of an organization might mean you are more accessible to people who are typically oppressed by organizations (especially health and mental health organizations). The sustainability piece I’m totally feeling right now. That might be the toughest one to figure out, but that also has little to do with your skills as a narrative therapist (cause you are amazing with that), and everything to do with capitalism and gatekeeping of access to mental health care.”

“I’ve often had these ideas and fears along the way…especially when starting out….it gets pretty scary at times…but not as scary as some other places I’ve been. There is a real accountability with the folks we meet when doing this work in these ways….not just accountability as an abstract idea. Keep going till you can’t I say!!”

“All of those concerns are exactly why you are going to be & are great… its the self awareness … please remember to use a great narrative mentor of your own … I’d certainly pay for your services as one.”

“I don’t have any words of wisdom, but want to say that I also experience these feels and impostor syndrome likes to push me around. I’m only just starting to get to know the way that ideas in social work/counselling like “competence” and “credibility” and “professionalism” bully me into thinking that I don’t know enough and don’t deserve to be paid the “big bucks” unless I meet the “qualifications” and become “registered”. (oh man, just putting all those words into quotations felt good and took some of their oppressive power away for a moment!) Anyway, from not knowing you very long and having never met in real life, you’ve already offered me emotional support and been thoughtful and kind when you witnessed something happening that you felt wasn’t right. You reaching out to me at that time was exactly what I needed. I am thankful that you exist and that you are able to be there for your community members.”

I’m going to put these into a book of reassurance for myself, and keep it in my office.

I’m going to keep doing my work.

I’m going to keep cultivating my loving relationships, across the wide range of their expression, and I’m going to continue to speak the language of scarcity and fear while I’m doing it.

I’m going to let this be complex.

I think that’s my primary love language – if I love you, I will step into complexity with you and for you. And that’s also how I want to be loved, with contradictions and complications.

That’s what I have to offer, and what I hope to receive.

(Maybe with a little bit of ease in there, too, sometimes. Just a bit. A bit more. More. A little more than that. Okay… maybe a lot. Someday, a lot.)

by Tiffany | Feb 1, 2019 | Read Harder 2019

My second book for the Book Riot: Read Harder 2019 challenge was much easier than the first! (You can read that first post here.)

For the second book, in the category of “A book by an author of colour set in or about space,” I read Nnedi Okorafor’s book Binti, the first in a trilogy (link is to Shelf Life books). It’s a short book, only 96 pages, and it was fantastic. Okorafor is a Nigamerican author (a term she uses rather than Nigerian-American, as a way to honour her dual heritage). She has won numerous awards – most of her books have won or been nominated for at least one award.

Check out her TED talk on her website, which includes an exerpt from Binti. She says:

As the story progresses, she becomes not other, but more. This idea of leaving but bringing and then becoming more is at one of the hearts of Afrofuturism, or you can simply call it a different kind of science fiction.

Sci fi is one of my first literary loves, and there are, as Okorafor notes, many ancestors of science fiction (though I didn’t recognize this until I was quite a bit older). Not all science fiction comes from white men. (Nor did science fiction originate with white men – Mary Shelley, of course, but even before her One Thousand and One Nights includes proto-science fiction.)

Regardless of the origins, I love science fiction, and one thing that I have learned in a lifetime of reading sci fi and fantasy is that very often, the best authors of speculative fiction are people who look at the world from unexpected angles. And you know who does that very well? People who have experienced oppression and survival under unjust systems. Folks with privilege have more time and support for their writing, but marginalized authors can often more easily imagine stories that move us beyond our standard paradigms.

I feel like I need to preemptively state that obviously straight, white, abled, neurotypical, educated men can write good speculative fiction. I loved the entire Ender series, and when I read Ender’s Game in elementary school it was mind-blowing. (I won’t read the series again, most likely, because Orson Scott Card has politics that are so far outside what I consider just or remotely acceptable, but that didn’t stop me loving his work before I learned about him as a person.)

And, of course, of course, Terry Pratchett’s fiction is profoundly concerned with issues of justice, and Neil Gaiman is always and forever a favourite. American Gods is comfort reading, and so is Neverwhere. And Pratchett’s books have gotten me through more than one depression.

But still. I will give my time and energy and money to marginalized authors, as often as possible, as intentionally as possible. (This is another reason I am so irked at myself for my initial mistake in the first category!)

So, Binti.

I loved so much about this book. The vivid descriptions of the material world – the smells, tastes, colours, and especially the textures – were captivating. Binti’s experience of being stereotyped and discriminated against both by her fellow humans and by the alien Meduse was so moving.

Binti is part of the Himba tribe, and one of my favourite details was that the Himba people in the book, based on the Himba in Namibia, excel at mathematics. This feels important, because it directly counters the racist assumptions of the other humans in the book, and it also counters the racist preconceptions of readers regarding Indigenous communities with non-colonial cultures.

I also really appreciated how the book talked about conflict, honour, and how we make assumptions about other cultures. For such a short book, there was so much to reflect on.

It was super good, and I’m hoping to read the rest of the trilogy, too.

(Though next on my list is tackling another category in the challenge. Next up, a book by a woman and/or an author of colour that won a literary award in 2018. I’m already halfway through Esi Edugyan’s Washington Black, and I’m loving it.)

by Tiffany | Jan 26, 2019 | Downloadable resources, Groups, Identity, Intersectionality, Narrative therapy practices, Writing

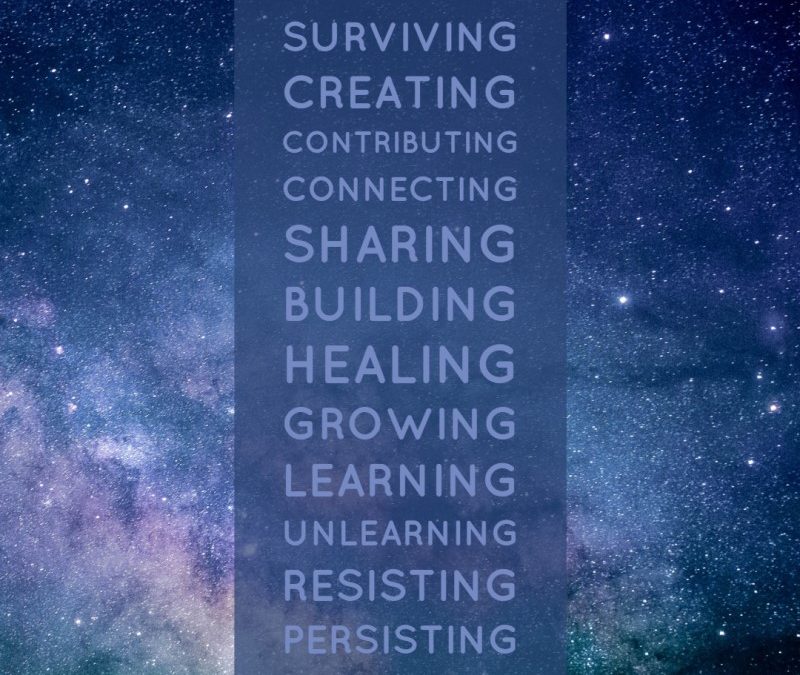

Image description: On a deep blue cosmos background. Text reads: Surviving Creating Contributing Connecting Sharing Building Healing Growing Learning Unlearning Resisting Persisting

What is this document all about?

This document is the result of a ten-day narrative therapy group project that ran from December 21 to the end of the year in 2018. The purpose of this group was to counteract the pressure of New Year’s resolutions and shift the focus onto celebrating the many actions, choices, skills, values, and hopes that we had kept close in the last year, and to connect ourselves to legacies of action in our communities.

Celebrating our values, actions, and choices may seem trivial, but we consider it part of our deep commitment to anti-oppressive work and to justice.

We hope that this project will stand against the idea that only certain kinds of “progress” or “accomplishment” are worth celebrating.

We want to invite you to join us in celebrating all of the ways in which you have stayed connected to your values, joined together with your communities, stood against injustice and harm. We want to celebrate all of the actions that you have taken in the last year that were rooted in love and justice.

Although this project was focused on the end of the calendar year, we hope that you find this helpful at any time when you are invited to compare your “progress” to other people or to some societal expectation. We think this might be particularly helpful around birthdays, anniversaries, major life transitions like graduations, relocations, retirements, gender or sexuality journeys, new experiences of diagnosis, and, of course, if you’re feeling the pressure that often comes with New Year celebrations!

This project is informed by narrative therapy practices.

Narrative therapy holds a core belief that people are not problems, problems are problems, and solutions are rarely individual. This means that although we experience problems, the problems are not internal to us. We are not bad or broken people; we are people existing in challenging and sometimes actively hostile contexts. We recognize capitalism, ableism, racism, transantagonism, classism, heterosexism, and other systems of harm and injustice, and we locate problems in these and other contexts. We recognize that people are always resisting the hardships in their lives. This project is meant to invite stories of resistance and stories of celebration.

Narrative therapy also holds a core belief that lives are multi-storied. What this means is that even when capitalism, white supremacy, and other systems of oppression are present in a person’s life, that life also has many other stories which are equally true. A person’s story is never just one thing; never just the struggle, never just the problems. This project hopes to invite a multi-storied telling of the year – one that honours hardship and resistance but recognizes that there are also stories of joy, companionship, connection, and play. We know that you are more than your problems.

When we are reflecting on our past year, shame and a sense of personal failing can be invited in – we might feel like we haven’t done enough, and that our reasons for this “not enoughness” are internal. This project hopes to stand against these hurtful ideas, and instead offer an invitation to tell the stories of your year in ways that are complex and compassionate.

Perfectionism and comparison can show up at the New Year, at birthdays, at anniversaries and graduations. But you are already skilled in responding to and resisting hardships. We know that you can respond to any hurtful narratives that show up and try to push you around. We are standing with you as you find the storylines in your year that are worth celebrating.

We know that it is a radical act of resistance to celebrate your life when the culture around you says you are not worth celebrating. If you are fat, poor, queer, Black, brown, Indigenous, trans, disabled, neurodivergent, a sex worker, homeless, living with addiction, or in any other way pushed to the margins and rarely celebrated, this project is especially for you. Your life is worth celebrating.

David Denborough and the Dulwich Centre have outlined a Narrative Justice Charter of Storytelling Rights and this charter guides this project.

My hope is that each of you feels able to tell your stories in ways that feel strong. I hope that you each feel like you have storytelling rights in your own life.

Here is the charter (link is to the Dulwich Centre post):

Article 1 – Everyone has the right to define their experiences and problems in their own words and terms.

Article 2 – Everyone has the right for their life to be understood in the context of what they have been through and in the context of their relationships with others.

Article 3 – Everyone has the right to invite others who are important to them to be involved in the process of reclaiming their life from the effects of trauma.

Article 4 – Everyone has the right to be free from having problems caused by trauma and injustice located inside them, internally, as if there is some deficit in them. The person is not the problem, the problem is the problem.

Article 5 – Everyone has the right for their responses to trauma to be acknowledged. No one is a passive recipient of trauma. People always respond. People always protest injustice.

Article 6 – Everyone has the right to have their skills and knowledges of survival respected, honoured and acknowledged.

Article 7 – Everyone has the right to know and experience that what they have learnt through hardship can make a contribution to others in similar situations.

However you end up using this resource, we would love to hear about it.

You can send your responses to Tiffany at sostarselfcare@gmail.com, and Tiffany will forward these responses on as appropriate.

Access the full 58-page PDF here.