(This is an expansion of a post that was shared with my Patreon patrons last month.)

I am learning how to do narrative therapy, how to be a narrative therapist, how to engage with my clients in ways that are narratively-informed. But what does that mean? What is narrative therapy? What does a narrative therapist do? What benefit does narrative therapy offer?

One of my favourite things about narrative therapy, and the piece that comes most easily to me, is the creation of documents to extend conversations from one individual or group out into a wider community – collecting, formatting, and sharing the insider knowledges that marginalized communities have developed and are using to resist injustice. I create courses, interview communities and generate resources and posts, host workshops, and I love when this facilitation work can be extended into a shareable resource or document.

Since documentation is my jam, I am going to create a series of blog posts that explore and share some of my favourite pieces of narrative practice. If you’re interested in these practices, and you’d like to set up a narrative session, or ask me further questions, comment or send me an email! My goal with this series of posts is to invite you into the process, offer you some tools that you can try out on your own, and maybe even entice you to get in touch and work with me.

In this first post in the series, I’m going to talk a bit about collective documentation and share an experience from the Advanced Narrative Skills teaching block that I attended recently.

(This story is shared with the permission of my collaborators, Julia and Tarn.)

Part of narrative practice is the creation of collective documents. These are documents that are meant to honour shared experience without erasing difference, and they are often used to make visible the skills, stories, and knowledges that people use to get through difficulties or resist injustices.

At the teaching block, we spent some time in groups of three, practicing this work. We each took turns being the interviewer, the interviewee, and the witness. The job of the interviewer was to listen to carefully, notice the phrases that were repeated or the themes that were emerging, and ask questions to elicit rich descriptions and preferred outcomes. (This idea of preferred outcomes or stories is one that I’ll come back to in a later post.) The job of interviewee was to respond to the questions. And the job of the witness was to take notes, which is often referred to as “rescuing the said from the saying of it” (this is a phrase of Michael White’s, explored in some depth in this article by David Newman).

This “rescuing” (which can be a problematic word to use, especially for white therapists working with people of colour, because there is a long and violent history of “rescue” being something done to marginalized folks, done by privileged folks) is used in many therapeutic documents, not just collective documents. (In a later post, I’ll write about some other types of therapeutic documents, and how I use them.)

Tarn, Julia, and I each asked, answered, and “rescued” on the following prompts (from the “Generating material for collective documents: What gets us though hard times” hand-out in the University of Melbourne and Dulwich Centre Master of Narrative Therapy and Community Work):

- Describe something that gets you through hard times

- Share a story of a time when this special value, belief, skill, or knowledge has made a difference to you or others

- Speak to the history of this skill, value, or belief. How long have you done this? Who did you learn it from/with? Who has recognized this /acknowledged this? Who would be least surprised to know about this?

- Is this linked to particular groups, family, communities, or cultural history of which you are a part? Is this linked to collective traditions and/or cultural traditions?

Then we each had an opportunity to hear what the “rescuer” had recorded while they listened to us being interviewed, and to correct or change or add to the story that we heard back. This is a critical part of narrative therapy, and part of my practice – you are the expert in your own experience, and you have control over the story that you tell and that is told about you within the therapeutic setting. Your words, your meanings, your stories – those are yours.

One thing that I appreciate about narrative therapy is that there is an accountability back to the people we are working with, to ensure that their stories, words, and experiences are taken up and interpreted in ways that feeling honouring, respectful, and accurate. This is part of how we resist pathologizing or further oppressing the people that come to us for help in navigating their stories.

Once we’d had a chance to try out each of the three roles, we collaborated on creating a document. We went for a long walk together through the park near the Dulwich Centre, and talked about where we noticed echoes and resonances between our stories. Once we found the thread that we wanted to use to tie the stories together – in our case, it was an experience of flow between togetherness and aloneness – we wrote the document through a series of drafts, shared back and forth and added to by each of us.

This is the document we created:

Together and Alone: How We Get Through Some Hard Times

A window into some Hard Times.

In Calgary, Tiffany is making a strong Earl Grey, adding double-fold vanilla extract and vanilla sugar, frothing hot milk, and assembling it all in a blue-and-purple octopus mug. The skill of the London Fog.

In Kathmandu, Julia is making a cup of coffee and writing three pages in the quiet of the house before bringing her practice into group sessions, where she will rescue words, shape them into poetry and stories, and share them back. The skill of writing.

In the Blue Mountains where she grew up, Tarn is sitting on a rock, the river far below, gum trees and black and white cockatoos all around, and across the river the white stripes of gum in the deep green of the trees. The skill of going into places of space and nature.

These are very different skills.

They have very different histories.

Tarn grew up on 50 acres of bush land, and the birthmark on her forehead is the same shape as Tazmania, where her parents have hiked every year, for 45 years. Now she lives in the redness and dryness of central Australia, near Honeymoon Gap, surrounded by all that resilient life, trees that have adapted and grown prickly and dry. She’s loved the land since she was tiny, and has made choices to live where she can get out into that vastness. But even in the city, she finds the flowers on the ground and the mice scurrying through the bushes. This is a skill with deep roots.

Julia learned to love writing stories at the same time she learned to write. Her stories were a survival strategy during a difficult time, and she loved books and reading. She lost touch with her love of writing after a betrayal of trust by a teacher, and now that she has it back, she is learning how to use it for herself and for others. This is a skill that has been reclaimed.

Tiffany learned to make London Fogs when they were housebound with pain, when the kitchen was as far as they could get in a day. Now they can move again, walk again, get out to cafes again, but the London Fogs have stayed, and have become a cherished ritual shared with others. This is a newer skill.

Despite all this diversity in history and expression, there is resonance.

There is a flow here, between togetherness and aloneness and everything in between.

How we engage with the flow is unique to each of us – Tarn connecting to generations of people who have lived on and loved the land through time spent alone – togetherness in the alone time; Julia, who grew up with books as friends and teachers, writing alone before writing with others; Tiffany engaging a skill learned in the isolation of illness and now shared with friends who are struggling.

But, despite the fact that we each enter the flow in our own ways and with our own histories, we each bring both solitude and multitude into these skills that get us through hard times.

We wonder how others engage with aloneness and togetherness, and how people find other flows that include other ways of getting through hard times. We especially wonder where these diverse flows lead.

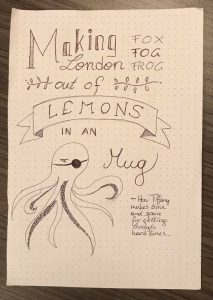

The next day, Julia shared this drawing with me, which I am planning to frame and hang in the office where I meet with clients.

Image description: A piece of art made for my by my classmate. Text reads ‘Making London Fox/Fog/Frog out of Lemons in an Mug ~ How Tiffany makes time and space for getting through hard times.’

The fox/fog/frog piece is an inside joke based on some pronunciation chaos, and the art itself has become another part of the collective document, and a gift that tethers me back to the idea of community, connection, and collaborative learning.

So, how does this have the potential to help my clients?

The idea that the skills, values, beliefs, or knowledges that get us through hard times have their own histories, their own roots into our communities, and their own rich stories is one that can be incredibly helpful when we are struggling. Often, we breeze past the skills, beliefs, values, and knowledges that get us through our days – small things, like a mug of tea, or larger things, like the ability to plan a trip or create art.

Narrative therapy offers practices to help us recognize, honour, and document these skills, beliefs, values, and knowledges.

This can be useful for groups, such as partners or family groups going through a hard time. It can also be useful for individuals. And the process of documentation can help translate those skills, beliefs, values, and knowledges into something tangible and material, that can be reviewed when needed, or shared.

If you’re going through a hard time, maybe this practice will help! You can answer the questions for yourself, or with someone in your family, friend group, or community. You can also create the document yourself. And if you’d like help with it, I would love to work together.