by Tiffany | Mar 28, 2019 | Climate, Grief, Narrative therapy practices

content note: climate existential dread, mention of suicidality

An earlier version of this post was available last week to supporters of my Patreon.

The other day, I made a really delicious salad for dinner, and as I sat there eating it, and enjoying it, and thinking about all of its components, I was, again, overcome with dread about the future of food security as climate change worsens.

This is a post about how fears about climate change are showing up in my life these days, and about how I hope to use narrative practices to respond to these fears in my own life and in the lives of community members who consult me. Many people in my communities, myself included, are experiencing a pervasive sense of hopelessness and powerlessness.

Narrative therapy suggests that we are never passive recipients of hardship or trauma. That people are always responding to the problems in their lives. I believe this is true, even when the response is not outwardly (or sometimes inwardly) visible. I want to find ways to speak about climate grief, climate fear, climate anger, in ways that honour our values, our skills, and our legacies of response. This post is one effort in this direction. I hope that there will be more. I hope that you will join me on the journey.

I think about climate change, and about how it will impact food security and the necessities of life, so often.

I think about the wealth gap that already exists and is worsening globally, and I think about how so many of my communities are already living with financial precarity. I think about what the salad I made should cost if we paid what we need to for carbon, and I think about how drastically my diet would need to change. I think about self-sustainability and I feel my aching body and I know that I will not be able to grow food to feed my family.

And this line of thought draws me into thinking about sustainability and self-sustainability. Self-sufficiency. Independence. I think that “self-sustainability,” expressed as individualism, is just another tentacle of violent neoliberalism and I reject it. Community care forever. But still. How? And so, bumping up against another problem (the influence of individualism on our dominant narratives), I encounter again The Dread.

I have nightmares about the next generation starving. My stepkids, my neiphlings, the children in my extended community, and in the vulnerable communities I witness from a distance.

Starvation is the most frequent recurring nightmare I have when it comes to climate change. It haunts me at least once a week.

It also makes me think about how environmental racism and environmental violence are not new; how Indigenous children and Black children have already been facing the kind of food scarcity that I have nightmares about. How the Black Panthers instituted school meal programs to try and address these issues long before climate change became such an urgent issue. But even though environmental racism and violence are not new, the people who have already been facing these harms will also mostly likely face the escalating harms more quickly and more directly. We can’t look at the past through idealistic lenses and pretend that children haven’t already been starving, but we also can’t use that as an excuse to ignore how much worse it will likely get.

Again, the dread.

But also threads of hope, and delight. The Black Panthers have descendants in Black Lives Matter, and food justice efforts exist in projects like Food Not Bombs, and in the Health At Every Size movement, and in Black urban growers (some of whom you can read about here) and Indigenous communities who understand how to care for the Earth in ways that capitalism and colonialism have tried (and failed) to erase.

I just bought adrienne maree brown’s new book, Pleasure Activism, and I am starting to read it. I think that pleasure is necessary, joy is necessary. How will we resist oppression and injustice, and respond to the challenges in front of us, without pleasure, without joy, without hope?

I want both: the fear that tells me what is at stake, and the hope that allows me to keep moving forward.

Right now I have a disproportionate amount of fear, and not a lot of hope.

There are reasons for this, and I refuse to disavow or invalidate my own fear and distress, or the fear and distress of my community members. But as much as I resist the pressure towards “positive thinking” that says feeling fear is the “real” problem, the fact is that I want pleasure and hope, too. I want joy. I want the full range of my emotions, and I want to be able to imagine a future for myself, for my communities, for the children coming after us. I want that for all of us.

Lately I have noticed my thoughts sliding sideways over into, “it would be good if I just died right now,” more often than I am happy about.

Last week I sent a message to Nathan Fawaz, one of my beloved humans, and said:

“Do you have a spoon for a big but short vent? I don’t need a solution but it is just sitting in my chest.

I just really struggle when I think about climate change. I don’t want to live through what is coming. I feel so hopeless and sometimes even suicidal. I won’t, because I think there is a role for people with my skill set in getting through what’s coming and I want to help, and I also think about the impact of that on my communities, but my desire to live does not coexist with my awareness of climate crisis. They do not overlap. When I think about climate change, my desire to live is gone.”

They replied, generously offering me the same kind of response that I would hope to offer someone who brought that vulnerability to me:

I am seeing such a strong value for supportive environments and our roles in cocreating them.

And such an affinity between environment and lifeforce/vitality.

Such a keen and important sensitivity.

I am sorry you are sad and that this is so hard.

I am sorry that there is so much detritus — both human and human-made.

I am sorry for all the disequilibrium.

Every word you wrote resonates so strongly.

They shared an idea that part of what is happening is akin to “ecoableism” – not being able to imagine any future without some expectation of wholeness or perfection on the part of the planet. An inability to see value or hope in an injured and ill planet. As people who are both in “painbodies,” we have faced this kind of ableism and have valuable insider knowledges into how to resist it. We have both felt the pressure of ableist narratives that frame bodies like ours (trans bodies, pain bodies, ill bodies) as less vital, less worthy. We have both resisting those narratives. We resist those narratives on behalf of our communities and other groups, too. (In fact, we talked about this in episode two of Nathan’s podcast, which you can listen to here.)

We cannot deny that we are causing harm and destruction to the Earth through our actions, that we are making a painbody for the Earth, but maybe we can find ways forward from within the crip and disability communities. What becomes possible if we could, as Nathan suggests, “think about my painbody. Your painbody. And all the painbodied people I know. The shimmering that is there. The incandescent connections. The community. The care. The skills that are exclusive to us.”

What becomes possible if we imagine ourselves in relationship with this struggling and suffering and overheating planet, as collaborators as well as defenders and protectors and destroyers. What if we imagine that there is something unique that we can offer, some gift of care or presence.

What if we imagine the unique insider knowledges that each marginalized community brings; the knowledges of persistence, resistance, healing, nurturing, tending, defending, adapting, restoring, remembering?

I am still figuring out what to do with this conversation and with these feelings. I suspect that in practice, this will mean that I keep tending my house plants and thinking about climate change. I’ll keep reading and talking about it. I’ll keep reaching for hope. And now, with this new language, I’ll start watching for where my insider knowledges into ableism might offer me new paths forward, new life-affirming and life-sustaining choices.

Imagining myself into a story of relationship with this planet, even this planet in a new painbody of our thoughtless design, feels hopeful in a way I had not previously had access to. Maybe it will also feel hopeful for you.

Here is another hopeful thing – this article by George Monbiot, “The Earth is in a death spiral: It will take radical action to save us.” Despite the title, this is one of the most hopeful articles I’ve read recently.

I also wanted to share some narrative questions that you can answer on your own. These are some of the questions I might ask someone who is consulting me for narrative therapy and expressing the kinds of experiences and feelings I’ve been describing here.

- What is it about this situation that is causing you so much distress? Is there something that you hold to be precious or sacred that is at stake?

- How did you learn to cherish whatever it is that is at stake?

- What is your relationship with this cherished idea, location, person, or planet? What is one story that comes to your mind when you think about your relationship?

- Have you ever felt hopelessness or distress like this before? How did you get through that time?

- Is there a legacy of responding to hardships like the one you’re in right now, that you can join? Have other people also felt what you are feeling, or something like it?

- Do you have friends or family members or role models who know what you are experiencing, and may be experiencing similar?

- What is it that keeps you in this situation? What are you holding onto, what are you valuing, that has prevented you from ‘checking out’?

- Is there anyone in your life who knows how much you are struggling with this? Do you think it makes a difference to this person that you continue to resist the problem?

- What does your distress say about what you cherish or consider valuable?

I ask myself these questions, and they are not easy to answer.

But I also know that I have strong values of justice and access and collective action. I know that these values can sustain me. And I know that you, too, have strong values and that connecting to these values is possible.

And I know that we can choose to welcome our despair as much as we welcome our actions of resistance and resilience. We can bring curiosity to The Dread, and ask what matters, what’s at stake, and remind ourselves of why we care so deeply. We can honour the depth of our fear and our grief and our anger.

Our despair is as valid as our resistance and resilience. The two can coexist.

We are multi-storied people, with many equally true and sometimes contradictory stories. And this is a multi-storied time. There is no need to flatten it down to a single narrative. Hope and fear. Pleasure and despair.

There is space for all of it.

The whole complex salad of it.

by Tiffany | Mar 12, 2019 | Narrative therapy practices, Read Harder 2019

At the end of last month I finished up the audiobook of The Widows of Malabar Hill by Sujata Massey, for the category of “a cozy mystery.”

February was exceptionally busy (and high pain) for me, so I was pretty distracted through many parts of the book, but I listened while I was doing admin work and laundry and dishes and driving. I’m pretty excited about having finished a third book in the month of February!

So, first impressions:

I loved this book.

I would not have identified myself as a fan of the mystery genre when I started the Read Harder challenge. It’s not a genre that I seek out, but this book inspired such a strong sense of nostalgia in me – I remembered many hours spent watching Sherlock Holmes and Poirot and Inspector Morse and Cadfael and Lovejoy with my family, and I connected to that sense of delight and curiosity that accompanies a mystery. It had been years since I thought about any of those shows. (With the obvious exception that I squealed delightedly at seeing Ian McShane as Odin in American Gods.)

This experience of realizing that I do enjoy a genre was really interesting to me, because one of the core principles of narrative therapy is the idea that lives are “multi-storied” – that there are many true stories of a single life, and they might contradict each other but they can still coexist. I would have not identified myself as a mystery lover, but I discovered (rediscovered) that I do actually love mysteries, and I have loved mysteries for a long time! I love Elementary, but I had considered my love to be more about the gender politics and my epic crush on both Lucy Liu and Jonny Lee Miller.

This was such a lovely invitation to become close to parts of my history that I had grown distant from, and it was really cool to see some of the principles I’ve learned about in the process of becoming a narrative practitioner become so clear in my own life.

Even beyond this little narrative adventure, the book itself is delightful.

Perveen Mistry, a Parsi and the first woman lawyer in 1920s Bombay, is fierce and feminist, and her character was inspired by Cornelia Sorabji, the first woman to pass the Bachelor of Civil Laws exam at Oxford.

One of my favourite things about the book was the focus on cultural context. Perveen is critical of British colonial rule, and her politics are woven throughout the book. She also talks about the different cultural groups present in Bombay and Calcutta (the two cities where the book takes place).

One thing that I felt was missing was a robust class analysis. There’s not much of it, and like many books and movies and shows, taking the economic mostly out of the picture makes it easier to bring forward other issues. I understand the benefits of locating all of the main characters in the upper class, and I did appreciate that despite the setting, there were moments of class analysis. Most notably, I appreciated when Perveen responds to a British woman’s question about safety, based on the fact that most major crimes in Bombay were committed by servants, by noting how many of India’s people live in poverty (meaning, most of the people in the country are poor, so of course most of the people committing crimes are poor), and how they are more likely to be arrested and convicted than a wealthier person who did the same thing. I am always here for a call-out of carceral injustice.

The gender politics in the book were central. A significant portion of the book takes place in the Farid zenana, where the Muslim widows (of the title) observe purdah (separation of the sexes). There are moments when Perveen (and by extension the author, and by invitation the reader) expresses sadness and concern for the purdahnashin, for their lack of freedom and access. However, the book resists leaning too hard into this perspective, challenging both Perveen and the reader by revealing the widows to each have more agency and more insight than anticipated. And the Muslim women are not singled out as uniquely vulnerable to exploitation – the Parsi tradition of secluding menstruating women is also prominent, and critiqued.

(Reading this book as a white, 21st century Canadian, there is an easy invitation to locate myself in a position of moral judgement when it comes to these cultural practices, but I tried as a reader, and will try as a reviewer, to refuse that position. Christianity, which is my own cultural background, has its own long and ongoing history of violent misogyny. I do think that there is a real risk of readers in my social context engaging in judgmental voyeurship, but that’s a problem with white supremacy and ongoing colonialism, rather than a problem with the book itself.)

Although British colonial power is evident throughout the narrative (Indian Independence Day wasn’t until 1947, and the book takes place between 1916 and 1921), the focus is not on either British control or British customs. Sujata Massey consistently brings a focus to the long cultural traditions of the Indian communities, particularly the Parsi communities (Perveen talks about her ancestors arriving hundreds of years prior from Persia) and the Muslim communities. This pushes the British out of the center of the narrative, and creates a sense of complex and ongoing Indian culture.

I really enjoyed this book. February was a difficult and emotionally draining month, and The Widows of Malabar Hill was a welcome lightness threaded through the background. (And the narrator was great. Very highly recommended.)

You can read my other reviews for the Read Harder 2019 challenge here!

My review of Binti for “a book by a woman and/or an author of colour set in or about space.”

My review of When They Call You A Terrorist for “a book of nonviolent true crime.”

My review of Washington Black for “a book by a woman and/or author of colour that won a literary award in 2018.”

My review of Fifteen Dogs for “a book with an animal or inanimate object as a point of view narrator.”

by Tiffany | Mar 11, 2019 | Gender, Identity, Intersectionality

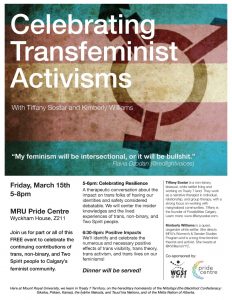

Image text:

Celebrating Transfeminist Activisms

“My feminism will be intersectional, or it will be bullshit.” ~ Flavia Dzodan (@redlightvoices)

With Tiffany Sostar and Kimberly Williams

Friday, March 15th 5-8pm

MRU Pride Centre

Wyckham House, Z211

Join us for part or all of this FREE event to celebrate the continuing contributions of trans, non-binary, and Two Spirit people to Calgary’s feminist community.

5-6pm: Celebrating Resilience

A therapeutic conversation about the impact on trans folks of having our identities and safety considered debatable. We will center the insider knowledges and the lived experiences of trans, non-binary, and Two Spirit people.

6:30-8pm: Positive Impacts

We’ll identify and celebrate the numerous and necessary positive effects of trans visibility, trans theory, trans activism, and trans lives on our feminisms!

Dinner will be served!

Tiffany Sostar is a non-binary, bisexual, white settler living and working on Treaty 7 land. They work as a narrative therapist in individual, relationship, and group therapy, with a strong focus on working with

marginalized communities. Tiffany is the founder of Possibilities Calgary. Learn more: www.tiffanysostar.com.

Kimberly Williams is a queer, cisgender white settler. She directs MRU’s Women’s & Gender Studies

Program and is a long-time feminist theorist and activist. She tweets at @KWilliamsYYC.

Co-sponsored by: WGST: MRU and The Pride Centre

Here at Mount Royal University, we learn in Treaty 7 Territory, on the hereditary homelands of the Niitsitapi (the Blackfoot Confederacy: Siksika, Piikani, Kainai), the Îyârhe Nakoda, and Tsuut’ina Nations, and of the Métis Nation of Alberta.

Content note for referencing a transantagonistic event and rhetoric.

This event has been pulled together quite quickly, and I’m so proud to be involved.

It’s a two-part event celebrating transfeminist activisms, and it will be happening on March 15 from 5-8 at the SAMRU Pride Centre at Mount Royal University.

Although this event is a response to another event being hosted earlier in the day at MRU (which I’ll describe below), I think the event is important either way.

Trans lives, and the validity of trans existence, is considered a reasonable topic for debate. It’s considered reasonable and valid to debate whether trans folks are “really” their own gender, to debate whether trans kids exist and deserve gender affirming care, to medicalize, pathologize, and infantilize trans individuals, refusing to recognize our self-knowledge and the fact that we are experts in our own experiences.

There is also a dominant discourse that pits trans activism against feminist activism, ignoring and erasing the long history of trans activism that supports and has enhanced so much feminist activism!

In Transfeminist Persectives, author Anne Enke writes:

Just about everywhere, trans-literacy remains low. Transgender studies is all but absent in move university curricula, even in gender and women’s studies programs. For the most part, institutionalized versions of women’s and gender studies incorporate transgender as a shadowy interloper or as the most radical outlier within a constellation of identity categories (e.g., LGBT). Conversation is limited by a perception that transgender studies only or primarily concerns transgender-identified individuals – a small number of “marked” people whose gender navigations are magically believed to be separate from the cultural practices that constitute gender for everyone else. Such tokenizing invites the suggestion that too much time is spent on too few people; simultaneously it obscures or reinforces the possibility that transgender studies is about everyone in so far as it offers insight into and why we all “do” gender.

Bringing feminist studies and transgender studies into more explicit conversation pushes us toward better translation, better transliteracy, and deeper collaboration…

This event has a goal of inviting that explicit conversation from the foundational understanding that trans activism can enhance and support feminist goals, and that feminism can also enhance and support trans activism. This is a celebration of translation, transliteracy, and collaboration.

And it is in response to a debate.

As some folks in Calgary may have seen, on March 15 the Mount Royal University ‘Rational Space Network’ will be hosting a debate on the topic of “does trans activism negatively impact women’s rights.” Meghan Murphy, the founder of Feminist Current, will be arguing the “yes” side. For folks unfamiliar with Meghan Murphy, she is very vocal about her anti-trans, anti-sex worker views.

The fact that this debate is happening at all is part of the background radiation of trans lives – the knowledge that we are debatable. Our worth, our role, our nature – debatable.

This is actively harmful to the well-being of trans folks, especially trans women (who are Meghan Murphy and most TERFs preferred targets).

So, this event includes a one-hour therapeutic conversation where we can talk about these harms, followed by an hour-and-a-half conversation where we can celebrate the contributions of trans activism to our lives. Because, as Anne Enke notes, we all “do” gender, and trans folks have expanded what is possible for all of us, cisgender folks included.

As a note: I will also be attending the debate, which will be happening at 3 pm at Jenkins Theatre. I’ll be attending in support of the trans women arguing the “no” side of the debate. I’d love if anyone was able to join me for the debate, or for either part of the event following.