by Tiffany | Aug 13, 2017 | Health, Neurodivergence, Patreon rewards, Personal

This is a Patreon reward post, and the first draft of this post was available to patrons last week. At the $10 support level, I’ll write a self-care post on the topic of your choice during your birthday month. And at any level of support, you’ll get access to these (and other) posts early.

This post is for Shannon, who is one of the strongest and most courageous people I know. She deals with chronic anxiety and other health issues, and yet is always doing as much as she can with the tools and resources she has available. She is an inspiration to me. Her requested topic was sensory overwhelm – what it is and how to handle it.

I decided to take this prompt in a different direction than my usual, and drew a comic for her rather than writing a post. There’s a longer post on the Patreon in the first draft, so if you want my long and slightly incoherent ramblings about what sensory overwhelm feels like for me, you can check that out as a patron.

After thinking about it, though, I think the comic is better without the explanations. I realized that one of the ways I try to process and mitigate sensory overwhelm is by over-thinking it, analyzing it into the ground, intellectualizing it, because being present with it is just so effing uncomfortable. But that over-analyzing, over-thinking, over-intellectualizing gets in the way of getting through the experience.

When I lose myself in sensory overwhelm, it’s often in those moments of trying to think myself out of my body. Sometimes it works better to just try to stay grounded while the overwhelm overwhelms, to let it happen and trust that there’s another side to come out on, to breathe even when the sound of the breathe is too much, to push my shoulders down from my ears even when the movement is too much, to close my eyes and know that I am alive, I am okay, I will be okay, even when everything is coming at me amplified and awful.

So, here’s my comic. This is how I experience sensory overwhelm.

Image description:

Panel One: A disjointed stick figure, with none of the limbs connected. “I feel disconnected and out of sync.”

Panel Two: A stick figure stands and covers their ears. Yellow and red lines and wiggles surround their head. “Sound are overwhelming.”

Panel Three: A stick figure stands. The sun is in the top left corner of the panel. Red and yellow starbursts cover the stick figure’s head. “Light hurts my eyes.”

Panel Four: A stick figure stands. Green wiggly lines surround them. “Smells are so strong and bad.”

Panel Five: A stick figure stands, surrounded by a spiky red field. “I feel like one giant exposed nerve.”

Panel Six: No image. “Sometimes I lose myself for a while.”

Panel Seven: A stick figure sits cross-legged. Blue and green concentric circles radiate out from their torso. “Eventually I can breathe and centre.”

Panel Eight: A stick figure stands. “And then I am back in sync.”

by Tiffany | Aug 7, 2017 | Identity, Intersectionality, Neurodivergence, Patreon rewards

This is a Patreon reward post, and the first draft of this post was available to patrons last week. At the $10 support level, I’ll write a self-care post on the topic of your choice during your birthday month. And at any level of support, you’ll get access to these (and other) posts early.

This one’s for Stasha, who has been one of my most active supporters and cheerleaders. I appreciate her comments and insight so much. She was also the inspiration for the #100loveletters challenge that I’m currently running, and her willingness to be visible in her experience of working towards self-love is empowering an ever-widening circle of participants in the challenge and beyond.

Her requested topic was visibility, and the complexities of doing self-care while invisible or hypervisible.

These are two sides of the same issue –

Invisibility

Being invisible – having parts of your identity illegible and unrecognizable and unacknowledged by the people around you – can make you feel crazy and alienated from your own experience. Invisibility can become a deeply damaging, traumatizing experience of being gaslighted by the entire society around you.

Invisibility takes many forms. Often, invisibility brings the double-edged sword of ‘passing’ – we are invisible (in whichever of our identities is unwelcome in the context) and that invisibility causes incredible internal harm and pain while also granting us conditional privilege as we appear to belong to another, more welcome, more acceptable, more safe, group. Passing as straight. As cisgender. As white. As neurotypical.

There are so many identities that become rendered invisible in most contexts. Where the assumption of normativity – the assumption that we fit society’s definitions of “normal” – is stifling. Crushing.

Queer invisibility – the harm felt by queer folks in heteronormative spaces, where we are automatically assumed to be heterosexual. Our queer identities are erased by the assumptions of the people around us. It hurts. We have to choose, each day, in each interaction, which hurt we want to experience – the pain of erasure, or the battle of fighting to be seen. Do we come out? Is it safe to come out? What are the consequences of coming out?

Trans invisibility. The experience of trans men and women who ‘pass’ – who are perceived as their gender and assumed to be cisgender – often have their transness rendered invisible unless they come out, and this can be both painful and comforting. Sometimes at the same time. Is it safe to come out? Is it safe to get close to someone without coming out? (Passing is a hugely contentious and fraught issue.)

Non-binary trans invisibility is a whole other issue, and one that I can speak to more personally. I am ‘read’ as a woman in every context except those ones where I have explicitly and decisively come out as genderqueer, and even in those situations, the illegibility of my identity is often clear. I’ve said the words “I am genderqueer – I do not identify as either a man or a woman” and have still found myself lumped in with “us girls” or “the ladies” or whatever other assumptions of womanhood people have, even by people who have heard me come out and have acknowledged the validity of my identity. They are trying to see me, but they just… can’t. Don’t. Won’t?

Femme invisibility within the queer community – the assumption that women with femme gender presentations are automatically straight. Also within the queer community, bisexual invisibility – a huge issue that remains pervasive.

Invisible disabilities, both physical and mental. Invisible neurodivergences, and the incredible pressure on neurodivergent communities to ‘pass’ as neurotypical. (The fact that we consider it a marker of success if an autistic kid is able to get through a class and “you’d barely even know they’re autistic!” is such a problem.)

And other invisibilities, invisibilities of experience – the invisibility of addiction and the experience of being sober within intoxication culture (many thanks to Clementine Morrigan for that phrase), the invisibility of childhood poverty in academic and professional contexts, the invisibility of trauma.

One of my heroes is Amanda Palmer. In her book, The Art of Asking, she said that so much of her artistic life has been spent saying, over and over, in song after song, performance art piece after performance art piece, in every way, again and again – “see me, believe me, I’m real, it happened, it hurts.”

I saw her live at one of her kickstarter house parties, and she was talking about the experience of being a woman and being tied to reproductivity – that question of children being a defining question. Another person in the audience, a genderqueer person like me, but more brave than I was, pointed out that not everyone with a uterus is a woman, and not every woman has a uterus – that this experience is not tied so tightly to gender. Amanda Palmer blew past the question, erased it, made a comment about how if you have a uterus then you are a woman and you will have to deal with these questions.

It wasn’t malicious, but it was violent – invisibility is not neutral, it is not passive. Rejecting someone’s effort to be seen is never a neutral act. Being made invisible in that way, particularly after making the effort to be seen, hurts. It hurts a lot. It took me a few years after that to be able to listen to her music again, and I just started reading her book this week.

(It’s a separate issue – the necessity of making space for imperfection. The story is relevant, but the healing process is a post for another time. Amanda Palmer is not perfect but I still find so much value and even validation in her work. This is one of the most exhausting challenges of having invisible identities – we still need community among the people who can’t, or who won’t, see us.)

So, how do you do self-care while invisible?

And what about self-care while hypervisible?

Hypervisibility

Hypervisibility is a separate but related issue.

Hypervisibility is when, rather than being assumed to be part of the normative group, you are visibly Other and that otherness becomes your defining characteristic. It is as much an erasure as invisibility – you lose the nuance of your whole and complex self. When people see you, they don’t see you – they see your visible characteristics and don’t move past that.

Most often, hypervisibilities are written on the body. The colour of your skin. The sex you were assigned at birth. The size of your waist. The movement (or not) of your limbs.

I don’t experience hypervisibility very often – I’m white and thin, with class, language and educational privilege that helps me blend into most environments, and my disabilities are all invisible (unless I’m trying to be physically active). When I do experience hypervisibility, it is in contexts where my assigned sex or my gender presentation are conspicuous – primarily cis-hetero men’s spaces.

Hypervisibility brings the threat of violence. Racist, transphobic, homophobic, and sexist violence can all be sparked by the wrong person seeing you and seeing you. Violence against fat and disabled people is similarly tied to hypervisibility. Violence against homeless or visibly addicted people is similar.

Hypervisibility doesn’t offer the option of passing, and the fight is often chosen for you – rather than choosing between the harm of erasure and the harm of exposure, hypervisibility means constant, constant exposure. They don’t make an SPF high enough to protect from that.

It is possible to experience hypervisibility and invisibility at the same time – to be a Black queer femme. To be bisexual in a wheelchair. To be non-binary and homeless. In those moments of compounding erasure – one identity hypervisible, every other identity erased – self-care becomes even more challenging.

Self-Care and Visibility

It is an incredibly difficult thing to be a loving mirror for yourself when all around you are mirrors that either don’t see you, can’t see you, or only see some parts of you. But that is the core of self-care and visibility – the ability and the necessity of finding a loving mirror within yourself and within your communities.

Find that one friend who sees every part of you.

Be that one friend who sees every part of you.

Get to know yourself.

Get to know every part of yourself – the invisible bits and the hypervisible bits. Write it down. Make a list of all the things you are, and solidify yourself for yourself.

It can help to take a page from narrative therapy and write yourself a small Document of Authority that states who you are, and to keep it with you as a talisman in situations when you know you either will be invisible or hypervisible.

Another self-care strategy is to practice recognizing, naming, and countering the gaslighting that comes with both invisibility and hypervisibility. Start to notice when people make statements that assume you are something other than what you are, or that flatten you down to a single identity. Note them, name them (out loud or just to yourself) and counter them with the truth.

Speak yourself into being, and into complexity.

It is the hardest thing in the world.

It’s why representation matters so much.

But I believe in you.

I know that you are real, and that what you have experienced is real, and that what you are is real and valid.

You are the expert in your own experience.

You know who you are, even if you can’t access that knowledge consciously yet.

Good luck.

Further reading:

Hypervisibility: How Scrutiny and Surveillance Makes You Watched, but Not Seen, by Megan Ryland at The Body is Not an Apology. This post is brilliant, and is part of a two-week series that ran on the blog in 2013.

The 5 biggest drawbacks of hypervisibility (and what separates it from the constructive visibility we need), by Jarune Uwujaren at Resist. Another great post that clearly outlines the harms of hypervisibility and the double-bind of being expected to be grateful for being seen.

Hypervisibility and Marginalization: Existing Online As A Black Woman and Writer, by Trudy at Gradient Lair. Trudy’s work revolutionized my understanding of misogynoir and the specific issues facing Black women. Her writing is excellent, and this post is no exception. (She no longer blogs at Gradient Lair but has generously kept the content available there.)

Queer Like Me: Breaking the Chains of Femme Invisibility, by Ashleigh Shackleford at Wear Your Voice. There is so much to love in this post (and many of the posts on this site).

10 Ways to Help Your Bisexual Friends Fight Invisibility and Erasure, by Maisha Z. Johnson at Everyday Feminism.

The Importance for Visibility for Invisible Disabilities, by Annie Elainey. I rarely link to videos (because I dislike watching videos most of the time), but Annie’s are absolutely worth watching. Her engagement with disability, and so many other issues, is fantastic.

(I am so thankful for the work of women and femmes of colour who have generously offered their insight and wisdom and emotional and educational labour to create these resources. Many of these content creators and sites are reader-funded, and if you’re in a position to support them, that’s rad!)

by Tiffany | May 4, 2017 | Coaching, Identity, Narrative shift, Neurodivergence, Online courses

This book is an invitation for you to use the simple act of writing as a way of reimagining who you are or remembering who you were. To use writing to discover and fulfill your deepest desire. To accept pain, fear, uncertainty, strife. And to find, too, a place of safety, security, serenity, and joyfulness. To claim your voice, to tell your story.

– Louise DeSalvo, Writing as a Way of Healing

This course, Writing towards Wholeness: Expressive Writing for Self-Care and Healing, extends DeSalvo’s invitation (and draws on her excellent work, along with the work of many other fantastic writers). The course starts on May 8, and runs until June 19. In these six weeks together, we will learn what expressive writing is, how to use it, and how to care for ourselves through the process of writing our difficult stories.

Each week will include video content, writing prompts, exercises, and a scheduled live chat. The course is designed to be modular – if you’re not interested in the behind-the-scenes lit reviews, discussion of the hows-and-whys, or extra information, you can skip the video content. If you’re just interested in learning about the topic and trying it out later, you can skip the prompts and exercises.

The course is capped at 10 participants, and I’ll be available for individual cheerleading, coaching, and that gentle butt-kick of accountability for each participant individually, in addition to the content available to the group. As of May 3, there are 4 spots still available.

The time commitment for the course is flexible, but you’ll get the most out of it if you can spend 10-20 minutes writing, 4-6 days per week, in addition to the few minutes it takes to read the emails. The video content will be anywhere from 3-15 minutes per week, and the live chat will be 45-minutes per week. With an investment of 1-2 hours per week, you should see some significant progress. And if you do every exercise and read every link and watch every video, you could spend 3-4 hours per week (though I have absolutely no expectation of that!)

The cost for the course is $60, with sliding scale available. It’s $45 for patrons of my Patreon, and it’s free for coaching clients.

If you’d like to sign up, email me!

Week One:

- Introduction to the course and the core resource books

- How expressive writing works (and the limits of its utility)

- Designing a self-care plan

In Week One, I’ll give you a mini review of the current state of the scientific research into the healing effects of expressive writing. Expressive writing has been studied as a tool for healing since the first paper was published on the topic in 1986, and there have been hundreds of studies since. We won’t talk about all of those studies, but I’ll give you a brief overview to help ground you in the science behind the practice. We’ll also talk about the limits of expressive writing, and alternatives to writing. Drawing, dancing, mind-mapping, and other artistic forms of expression are welcome, and we’ll touch on the research that supports their benefits. In Week One, we’ll also bump up against the limits of the research. The fact is that we don’t know why expressive writing does and doesn’t work, and although we’re getting closer to answers, they’re still in the future.

You’ll also begin to design a personalized self-care plan in Week One. We’ll talk about how to identify your needs, and set yourself up for success.

Week Two:

- Narrative trajectories

- Personal anthologies

In Week Two, we’ll introduce the narrative side of the project. Drawing on David Denborough’s work with “everyday narrative therapy,” you’ll start to identify and explore your own life story. We’ll talk about personal origin stories, and how to create an anthology of your own formative positive moments. These positive story will work with your self-care plan to help give you a solid grounding in self-compassion and non-judgmental self-awareness. For many of us, the negative stories are easier to believe and easier to call to mind, so although this week is focused on the positives, it’s definitely going to be a bit uncomfortable at times. Good thing we have a self-care plan in place!

Week Three:

- Writing and trauma recovery

- Externalization

- Other benefits of expressive writing

Week Three will dig deeper into the specifics of how writing can be used to work with trauma and other issues (such as focus at work or school, or managing depression, anxiety, or other mental health issues). We’ll talk about how trauma impacts the body, and some of the research into the health effects of trauma. We’ll also talk about externalization, and start practicing seeing problems as being something outside of ourselves, rather than something inherent to ourselves. If that sounds weird and counterintuitive, don’t worry. I’ve got exercises and simple explanations to make it more accessible and engaging.

Week Four:

- Expressive writing

- Self-care

This is it. We’re doin’ it! In Week Four, we’ll put our self-care plan into full effect, and engage in four days of 15-20 minutes of writing about an emotional topic. If you’re a trauma survivor, don’t worry – you don’t have to write about the scariest or most challenging – we’ll talk about a wide range of potential topics and you can write about whatever feels right for you. You will have access to all of the course materials even after the course wraps up, so you can always come back to it as many times as you want.

Week Five:

- Reframing, reshaping, recovering

We’ll take the body of writing (or drawing, or talking, or dancing) that you’ve generated over the last month and start thinking about how it fits into our narrative trajectory – the path we want our lives to take and the path we see ourselves having already taken. We’ll talk about how to use the skills and tools we’ve gained so far to reshape and reframe our stories, and to use these narrative strategies to recover from traumas and difficulties.

Week Six:

- Tools for a sustainable practice

- Discussion and wrap-up

In our final week, we’ll talk about how to use these tools going forward.

I am so excited about this course. I have used writing as a coping and healing tool for decades, and writing has gotten me through some of the worst times in my life, and helped me appreciate some of the best. Telling our stories intentionally, compassionately, and wholeheartedly has the potential to change the way we see ourselves in the world, to help us feel centered and strong in the stories of our own lives.

by Tiffany | Feb 26, 2017 | Coaching, Health, Identity, Intersectionality, Neurodivergence, Patreon rewards, Personal

Dressed up as a Gloom Fairy – one of the self-care strategies that got me through university.

This is a Patreon reward post. At $5 per month, you, too, can have a personalized post on the topic of your choice during your birthday month!

Red Davis (one of the first people to back my Patreon! *heart eyes*) is a current student and good friend. He asked for “a post relating to disabilities and mental health disorders within a university, professional, or social context; recurring themes of self-shame, embarrassment, and self-imposed solitude often debilitate many in higher learning or work situations.”

I will admit, I struggled with this post.

I wanted to write it, of course. Helping people navigate these hostile contexts while existing on the margins is exactly what I want to do in my coaching and self-care resource creation. Not only that, but it’s a reward that I’ve committed to providing for someone who is dipping into a tight student budget to support me, and make this work possible.

But, wow.

Every time I sat down to work on the post, my own feelings of shame, embarrassment, and self-imposed isolation flooded through me.

I remembered, specifically, one afternoon in 2012, standing in a hallway at the U of C, probably the Social Sciences building. One of the little ones, too brightly lit, with old computers on white tables, and plastic chairs, and a few students wandering. Wearing my winter jacket, dragging my backpack on wheels because the fibromyalgia no longer let me carry all those books, on my cell with the campus dental office cancelling an appointment because I was having a panic attack.

That panic attack cost me $100 in a late cancellation fee, and I never rebooked. Now, 5 years later, that memory still sparks shame and anger, and an icy-gut feeling of humiliation over the fact that my panic attacks cost me so much money at a time when I had so little, and that they kept me away from necessary healthcare. (And they have continued to do so! That appointment would have been my first visit to a dentist in years, and when I said I never rebooked, I mean that I never rebooked. It’s on my to-do list for this week. Seriously. I’m gonna do it. For real. I swear.)

The memory is about the money, the shame of “wasting” money on a “ridiculous” mental health issue. Sort of. Maybe. I mean, the money is part of it.

But it’s also about the voice on the other end of the phone, the impatience and irritation of the receptionist, and the feeling of shame when I started to cry and she cut me off. “Sorry, no exceptions to the cancellation fee, if you were going to be unable to make it, you should have called yesterday.”

These feelings are deeply physical. Shame, humiliation, fear – these are all visceral reactions, gut feelings. 5 years after that phone call, I still feel the twisting in my belly as the shame winds through me.

And when Red touches on self-imposed solitude, this twisting shame belly is part of that. Shame, after all, is an isolating emotion. It pushes us away from each other, drags us off into dark corners to hide ourselves.

How do we reach out when we are captives of our shame?

But shame is not the only factor.

Time and energy are also factors.

How do we maintain our social circle when disabilities make the work of school or professional life take longer, and take more out of us?

When fibromyalgia arrived on the scene, stealing my energy and my reading comprehension, and for one horrific semester, my ability to write… everything took longer. Everything took longer. Crossing the street took longer! Reading a paper took longer, and took more out of me. I was tired at the end of a page, exhausted at the end of a chapter. I deferred coursework, missed deadlines, spent endless hours in doctors’ offices and at the disability resource centre – hours that were then not available for schoolwork or paying work or socializing.

The anger at no longer being able to operate as I had was immobilizing, and embarrassing. The shame was overwhelming. The exhaustion was beyond comprehension. It triggered a depression… or did the depression precede the pain? Those years are a dark smear of distress across my memory.

How do you make it through post-secondary or professional contexts when dealing with disabilities or mental health issues?

How do you survive?

How do you continue, knowing that your brain and your body are working against your ability to fit into these contexts?

In 2013, I did my first Year of Self-Care.

I needed it. Even through the blur of my distress, I knew that I needed it. I was falling apart. I was a wreck – physically, emotionally, mentally, financially.

I don’t honestly remember much from the beginning of that project.

I know that I was desperate.

When I was 18, at another desperate point in my life, I had done a Year of Independence in an effort to heal some relationship trauma. It was one of the highlights of my youth, remains one of my favourite experiences. I leaned on that, and set out some plans.

It wasn’t easy.

But one of my founding principles for that year was compassion for myself. The act of compassion and care, even when the feeling was unattainable.

I needed to start there, because at the time, my body and my brain felt like my enemies. I think that’s a common experience for people dealing with disability or neurodivergence. It’s hard to practice effective and sustainable self-care when you feel like your own enemy.

The Year of Self-Care included a lot of hit-and-miss experimentation.

During that year, I discovered how much I enjoy the ritual of tea, and that’s the year I learned to make London Fogs. I still make amazing London Fogs (though not as often as I used to – I need a new milk frother).

I also experimented much more intentionally with using outfits as armour and as a self-affirming tool. Gloom Fairy, The Pirate King, and Elf Commander all have roots in those Year of Self-Care experiments.

How do you continue, knowing that your brain and your body are working against your ability to fit into these contexts?

It was the year that the Wall of Self-Care went up, white boards with anxiety bubbles, and self-care lists, and my inspiration board.

It was the year I learned to swim, in order to challenge a phobia, and get my fibromyalgia pain under control, and prove to myself that I could.

It was the year of endless struggle, and I was lucky because it was also the year of infinite support.

It was a hard year. But it was a good year.

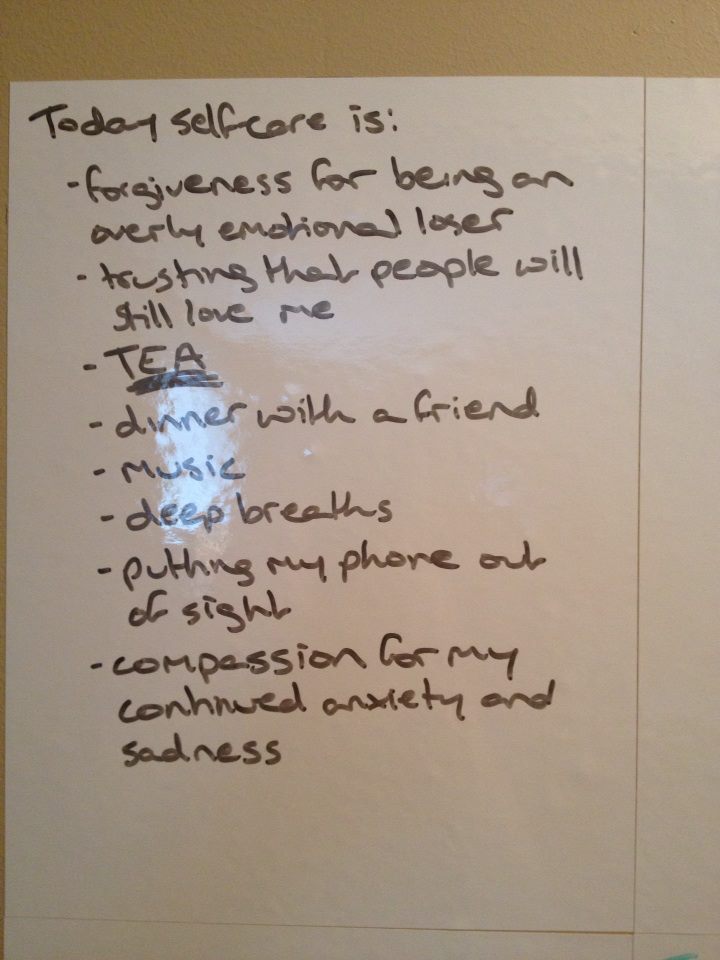

A list of self-care to-do items posted on Facebook in 2013 with the comment: This afternoon took a sudden, unexpectedly intense turn for the worse, so I hung up some stick-on white boards (expanding my wall of self-care) and made a list. Intentional self-care! For those of us whose default position is ‘the unfortunate person crying in the stairwell.’ Sigh.

A badge given to me by my friend Patti when I successfully managed to tread water.

A love note from my little niephling.

The biggest lesson from that year was that self-care is fucking hard. It’s hard. Making a cup of tea when you’re exhausted, and ashamed, and embarrassed, and feeling lonely despite your community – it’s hard. Reaching out for help? Holy shit, that is not easy. Doing anything other than wallowing is just really hard.

Making choices intentionally, and choosing compassion and care, it takes effort. And you fuck up, a lot. You fuck up all the time. It took a year and half to complete my Year of Self-Care (my “Year of Whatever”s are almost always a year and a half – either the new year to my birthday the next year, or my birthday to the new year. I like some wiggle room.)

In that year and a half, I made plans and failed to complete them. I made the same plan again and failed. I made a slightly different plan and failed in a different way. I made a totally new plan and still failed. I tried again and failed. I made schedules and failed to stick to them. I set goals and didn’t meet them. I dropped more balls than I kept in the air, and that’s okay.

That’s okay.

It doesn’t feel okay at the time. It feels awful. But that process of failing at self-care is an important part of the journey. Self-care has to involve deep compassion for your broken, aching self. It can’t all be celebrations and successes. It won’t be. If it was, you wouldn’t need it so badly.

In order to get to a place where you have effective and sustainable self-care practices in place, you need to go through the process of pushing against the resistance. The internal resistance, sure. The shame, the fear, the feelings of selfishness and the anxiety over failure. But mostly, mostly, the external resistance.

You have to smash your fist against the cost of self-care. That $100 penalty for a panic attack. The cost of admission to the pool. The cost of white boards. The cost of missed work hours. The cost of healthcare, even here in Canada. The cost of therapy. The cost of nourishing food. These costs that you cannot always afford. You have to run into that wall over and over and over until you find ways under, or through, or around it. And sometimes you don’t. Sometimes you can’t. Self-care cannot belong only to the financially secure. Those of us who are disabled or neurodivergent or otherwise marginalized are much more likely to be dealing with economic insecurity, to be living in poverty, to be stretched too thin, to have ends that not only don’t meet, they don’t even make eye contact. We deserve self-care, too. But it takes time to find those tools, because it’s much quicker and easier when you do have the money for it.

And you have to smash your fist against the unreasonable and inhumane demands of post-secondary and professional institutions. Deadlines and dress codes and disdain. I dropped a course I really loved because handwritten notes were mandatory for a huge percentage of the grade, but my hands hurt too much to write long-hand. More bitterly, I dropped out of the Arts and Sciences Honours Academy because the professor in third year required mandatory attendance, with no more than two exceptions for medical issues. “Breathe deeply and drink a mug of tea” doesn’t wash the salt from those wounds. Getting to sustainable self-care means feeling that sting, doing what you can with the resources that you have, trying to find ways around it. Finding the understanding professors, begging with the disability resource centre, paying the $25 to have a doctor write a letter saying that yes, you really do need these accommodations. It takes time, and it takes energy, and it takes a lot of permission to just be angry and bitter on your way to being calm.

And doctors… another wall, another round of smashing and smashing and smashing until you find the way through. Get the diagnosis, get the prescription, get the help. Or, sometimes, you don’t. Find other ways to cope.

The systems are not built for us.

It hurts to contort ourselves to fit within them.

That pain is real. That injustice is real.

There are ways forward. My Year of Self-Care made a huge difference for me. I’m not meaning to downplay the importance of doing that gritty work of developing more wholehearted self-care and self-storying strategies. But I get frustrated at resources that don’t acknowledge how hard this is, and how much the odds are stacked against anyone who differs from the straight, white, cisgender, able-bodied, neurotypical, class privileged norm.

When I started working on this post, I did what I always do at the beginning of a writing project. I opened a new Chrome window and I googled this shit out of my topic. I started with “self-care for students” and I found dozens of posts. Every post-secondary institution seems to have some kind of self-care guide for students. (Perhaps because post-secondary institutions are set up in such a way that any student who doesn’t have an extremely solid base of socioeconomic stability is pretty much fucked when it comes to mental, emotional, and physical health? Dunno, just a theory.)

These resources place a huge emphasis the individual doing everything possible to maintain their self-care

This resource from the University of Michigan is a perfect example.

“Taking steps to develop a healthier lifestyle can pay enormous dividends by reducing stress and improving your physical health, both of which can improve your mental health as well. Students with mental health disorders are at a higher risk for some unhealthy behaviors. You may find it challenging to make healthy choices and manage your stress effectively while in college. This section of the website will help you find ways to take care of your health, which can help you to feel better and prevent or manage your mental health symptoms.”

Look at that language! You’re at higher risk for unhealthy behaviours. You may find it challenging to make healthy choices. Gross. Gross! There is nothing there about how the structures and systems and expectations and normativity around you are the source of that distress, and put stumbling blocks in front of your movements towards “health.” It pushes the responsibility entirely onto the student who is struggling, and then wipes its hands clean. There’s good advice in that resource, but it comes in bitter packaging.

Even posts like this assume that the identity of “student” is also normatively able-bodied and neurotypical.

“College students’ ability to deny basic needs like sleep can oftentimes seem like a badge of honor proving we are reckless and young. At my school, it can seem like a competition to see who can stay up longer to study, and pulling all-nighters seems like proof we are true UChicago students. One’s talk of working grueling hours in the library is met with solidarity and sympathetic laughter, while taking a break or decreasing course load seems to be associated with weakness.”

College students who can’t meet that expectation are, I guess, not “true students.” When the article concludes that:

“If we want to improve our psychological and emotional health, college students could perhaps benefit from changing their mindsets and relationships to work. Taking breaks and letting our minds rest could be an effective strategy for achieving our goals in the long run, because stress or lack of sleep can hinder productivity. Maybe the next time a friend bemoans having to pull an all-nighter for a class, we can think about how our response may perpetuate a culture that idolizes self-destructive behavior. Perhaps rather than laughing or saying that we understand their struggle, we can gently encourage them to take a break. Or, if it’s you who’s putting in those late-night hours, maybe go home for sleep rather than the campus cafe for coffee. You deserve it. You matter, and your health matters.”

There is still the assumption that this is a choice, and that is not the case for every student.

So, in conclusion, it’s fucking hard. And it’s not your fault. And you can figure it out, but it will take time. And you will continue to run into walls.

Being your own ally is not easy. It’s even harder when there are complicating factors like disability, pain, depression, anxiety, or other chronic issues that aren’t going away. And it’s even harder when you’re in hostile environments like many post-secondary and professional contexts.

But I believe in you. There is a way forward. There is always a way forward.

by Tiffany | Feb 11, 2017 | Coaching, Identity, Narrative shift, Neurodivergence, Personal, Plot twist, Step-parenting

This post was available to my Patreon patrons on Feb 11. If you would like to see posts a week early, visit my Patreon.

This week was challenging. I say that most weeks, though. There’s so much change. I don’t know who I am within these new roles, and everything keeps shifting.

I’m not actually an ocean navigator, despite the wave in my logo. I’m terrified of water (that’s one major reason we picked the wave, and that will be another post). I navigate a metaphorical ocean, but still, I think that the best metaphors are grounded in some reality. And so I sometimes read about the ocean, and how currents work.

There are all kinds of different currents in the ocean.

There are surface currents, driven primarily by wind. Rip currents that happen when a large volume of water funnels through a narrow gap in a sandbar, or between rocks. There are upwellings and downwellings, which happen when the wind blows across the surface of the water and either deep water rises up to fill the displacement, or surface water accumulates if the wind blows it against a shoreline.

And there are deep water currents, too. Like the “global conveyor belt,” a deep-water current that circles the globe and is the foundation of the food chain. It moves more slowly than surface currents, and it takes a thousand years for a section of the belt to complete its journey around the globe.

And there are tidal currents, which switch directions and respond to the gravitational pull of the moon. Flood currents and ebb currents, predictable and cyclical and strong.

Metaphorically, and in reality, these various currents have a significant impact on the whole – whether it is the ocean influencing life across our planet, or the inner ocean influencing the self. The tides, or the deep water ribbons that move slowly and forcefully, or the surface with its rip currents, and its upwellings and downwellings (and the rich metaphor of algae bloom and anaerobic suffocation in the downwelling – the choking off of life when there is no connection to the deeper water – and in the further stretch towards recognizing how downwelling, even though it creates areas of reduced productivity, is necessary for the ecosystem because it allows for deep water ventilation – there are times when lower productivity is necessary for survival).

The sun setting on the ocean.

All photos in the post, unless noted, are copyright-free photographs via Pixabay.

So these metaphors, and these currents, and this difficult, difficult week.

Deep water currents change slowly. Climate scientists are worried about the global conveyor belt because increased rainfall and polar melt will change the salinity of the ocean, and therefore change its density. If the belt changes, everything changes.

And there are changes in my own deep water currents. They change everything.

My work life is changing. I have been aware, for almost a year now, that my steady day job is not guaranteed. The economy, changes in management, the nature of my role. It’s been almost a year of nearly constant low-level stress, with monthly peaking moments of intense anxiety (usually when my student loans come out of my account – lolsob). My day job – boring, predictable, reliable, and one that I am exceptionally good at – has been a constant for me for almost a decade. I’ve been with the same company, in various roles, for ten years. And I’ve been in this particular role for almost six. Seven? I don’t know. A long time. It’s been an anchor. Sometimes weighing me down, but also keeping me stable.

My work life is changing, too, because of this. The coaching and the self-care work, the workshops and resource creation and writing and trying to shape this into a career. The desire to move from work that is reliable and that I am reliably good at but uninspired by, to work that I am passionate about and personally invested in. I will be good at this. I will make a difference. But while I move towards that, there is chaos and uncertainty.

Uncertainty especially in my financial life. I have not been truly financially stable since I was married – my husband made a solid lower middle-class wage, more than enough to allow me to run my dog training business and weather the ups and downs of entrepreneurship, and to buy clothes and food and craft supplies without worrying about it, and to have hobbies and go out for dinners and have adventures. I didn’t worry about money, when I was married. And I have worried about money constantly, since divorcing. It is, like the work stress, a constant low-level hum of anxiety with regular surges to the surface. These tidal currents – the huge gravitational force of capitalism pulling deep fear to the surface.

And that financial anxiety is also tied to my relationships. This deep current originates in my family of origin, in watching the dynamic between my parents when it came to money, and agency, and independence, and reliance. Who earns it, who spends it, who makes choices about it. And then, my divorce and the year after I left, with months of rent on the credit card and groceries paid for by my best friend – a level of vulnerability and insecurity that I had never previously experienced, and one that still trickles icy through my memory, makes me wary of taking risks. And then time spent supporting a partner, who now supports me, and another partner who also supports me. And the vague sense of unease I have every time I require help, ask for a loan to bridge a financial gap, make a choice that may impact someone else.

And now the “someone else” is so complicated by the addition of two little elses. The new relationship of stepparenting. And knowing that my choices now are not just going to impact my financial stability, but also the financial stability of my relationship with my nesting partner, and rippling out from there to affect my stepkids, both neurodivergent, both requiring additional supports. And in addition to the worry about being able to provide materially there is also the worry about being able to provide emotionally and mentally. To heal the old wounds that I still carry so that I don’t pass them on, to adjust to this new role in a way that doesn’t place emotional weight on the kids as I adapt. The shift, such a huge shift, from knowing in a deep and fundamental way that I would never be a parent, to knowing that now I am a parent. And also, the drive to learn enough about the unique needs of these two specific kids, individuals, amazing little humans, to be able to help them, and to help my partner.

And that’s the key, that’s the deep water current that is changing right now – my very sense of self, in multiple areas.

And so then researching. Reading Understanding Stepfamilies: A Practical Guide for Professionals Working with Blended Families (in this, I am both the professional and the family – approaching my life, as I always have, from an academic perspective), reading Family Therapy and the Autism Spectrum: Autism Conversations in Narrative Practice, reading The Whole-Brain Child and The Real Experts: Readings for Parents of Autistic Children. Learning a whole new language, a new area of knowledge. And finding gaps in it – both when it comes to stepparenting and when it comes to parenting neurodivergent kids. Gaps filled frustratingly with the assumption of heterosexuality, monogamy, and cisgender identity, gaps filled with transantagonism, ableism, normativity and social pressure in so many bitter flavours it overwhelms my palate and leaves me gulping for fresh water in the form of writing, reading, trying to find connection and community and incorporate this work into my coaching because if I am falling into this gap, other people must be, too.

And also reading about coaching, about relationships, about narrative therapy – Opening Up by Writing It Down and Retelling the Stories of Our Lives and Levels 1 and 2 of the Gottman Institute ‘Gottman Method Couples Therapy’ and half a dozen other books and courses. And underneath all this research, which I love, is the slow tug of grief at leaving academia, because I decided not to pursue an MA in counselling psychology and instead started on this endeavor and it’s the right choice, and I will make a difference, and I will continue to be an academic and a researcher and a writer (writing a book! And learning how to do that). Independent scholarship is a real thing, and I will do it, but still, the changes.

Some of the books that I’m currently reading.

Photograph by Tiffany Sostar

And this change, this shift away from academics, is huge. Because deciding to finally go to university was a big deal. I had always wanted to. And I had been told, shortly after I graduated high school, that I didn’t have what it takes. I believed that story. That story became part of my core set of beliefs about myself. I was smart, I was a good writer, but I was not persistent. I did not have the “sticktoitiveness” to get through university. So I read academic theory on my own time (this essay – Reading Wonder Woman’s Body: Mythologies of Gender and Nation, by Mitra Emad, was my first academic love), and wrote nerdy papers about feminism and gender on my own time, and didn’t believe I could hack it in post secondary. Until I started dating someone who said “why aren’t you in school? You’re sending me links to feminist theory because you’re reading it for fun – apply to the University of Calgary.” And I trusted him. So I did it. And I graduated with a First Class BA Honours in English and a First Class BA Honours in Women’s Studies. I did it. I challenged that core story and I changed it. And I miss academics. As broken and abusive as that ivory tower is, still, I miss it.

And I miss myself within it.

And that’s the key, that’s the deep water current that is changing right now – my very sense of self, in multiple areas.

Who I am.

Who I am as a labourer – emotional, domestic, social, and other. Where and for whom and how I work, and how I get paid, and where my money goes and where it comes from, and how I spend my time, and my intellectual energy, and what I write and when I write it and who I write it for, and who judges it, and who judges me, and how I define my value and my worth, and where I find myself, and what I call myself, and who sees me and how they see me, and how I see me.

These are the ocean currents of my life, and myself. The deep water currents and the surface currents and the tidal currents. The core self, and the self in relationship, and the self in society.

So, these weeks are challenging. As I move through my life I am aware of the currents shifting, and I don’t know what the ecosystem looks like once they’ve shifted. Who I will be, how I will be, what I will be.

But change is constant, and it is not the enemy.

The Earth has experienced changes before, and I have experienced massive change, too.

I have faith in my ability to survive the chaotic betweentime, and I have faith that I will eventually settle into new patterns and find new wholeness and new peace.

I’m happy with how things are changing. I love coaching. I love this work. I love my kids. I love my partner, and my entire polyamorous pod. I love researching, and I love finding subversive ways to inhabit liminal spaces – bisexual, genderqueer, invisibly disabled, neurodivergent – I was made for the liminal spaces and the betweenings. Independent scholarship feels like an exciting new liminal space to step into. Just like stepparenting feels like an exciting liminal space to explore, with rich potential for writing and researching and offering help and hope to others. Just like parenting while queer, and parenting while non-binary, also feels liminal and rich with betweenness and both/andness.

This is an upwelling – the wind has blown hard across my surface and there is space now for deep water to rise, and bring new life to the surface.

It’s scary, but the ocean always is, for me.

I love it anyway.

by Tiffany | Jan 29, 2017 | Health, Identity, Intersectionality, Neurodivergence

This is the last in a four-part series exploring the Let’s Talk campaign. Part One is here, Part Two is here, Part Three is here. If you would like to support this work, please consider becoming a patron on my Patreon.

Let’s Talk about pushing the conversation out of the comfort zone – an interview with B.

B is a lawyer in Calgary whose family law practice is explicitly trans and queer-inclusive, and he is committed to social justice within family law. He used the Let’s Talk campaign as an opportunity to explicitly and directly address his own personal mental health struggles with his employer.

I know the Bell Let’s Talk day is really complicated. On the one hand it’s great to see the dialogue happen. On the other hand, it’s hard to get over the commercialization of this really important issue. It’s helpful to see celebrities speak out about mental wellness but it’s easy to feel like you’re only allowed to experience mental wellness if you’re a celebrity.

I think individual people can try to take advantage of the positive momentum behind this movement, though. I recently experimented with using Bell’s Let’s Talk day as a framework to address my own personal challenges with mental illness with my employer. I don’t know how it will work out. But I feel positive about my experiment and I’m hopeful it will work out.

I’m 32 years old. I’ve been a member of the Law Society of Alberta since 2010 and I’ve been an associate at the firm where I practice family law for 4 years. I like working where I do. Generally speaking, I think our management team is compassionate and actually cares about the people who work here. I know I’m lucky in that regard. However, like most businesses, profitability is still the bottom line. It’s impossible to be successful in our world without keeping a careful eye on productivity. Lawyers at my firm have targets; our value, as employees, is closely tied with the amount of money we make for the partnership.

In every year leading up to 2016 I maintained steady growth in my numbers. At various times, I have been the top associate in a number of areas. I bring in a lot of my own work, I have a good profile in the community, and I’m very productive. Up until 2016 I routinely received overwhelmingly positive feedback from the management team and from other partners. In 2016, though, a lot of that positive feedback dried up.

2016 marked an extremely challenging year for me, personally. My mother battled cancer throughout the year and ended up with a number of related and serious health conditions; my grandfather died; and a number of other personal things came up that created a very large black hole in my life that seemed to suck up everything I had to offer, and then some. I found myself in one of the darkest places I’ve ever been. Without getting into all of the details, all of the areas in my life that previously gave me fulfillment suffered in one sense or another. My career was no exception.

In 2016 all of my numbers shrank. I had to pare back all of my commitments in the community. I ended up putting off my continuing education (I am engaged in an LL.M and was scheduled to finish in 2016). I also became somewhat less involved in our firm culture (ie: attendances at firm dinners and firm events like our golf tournament). The impact of my mental wellness became real to me when, in a very short span of time, a few members of the partnership came to me with the exact same feedback: “We hope you’re ok. A bunch of us at the partnership table noticed you’re not your usual self.” When I asked for more specifics I was simply told that the partnership thought of me as a leader in positive energy around the firm and that people were starting to notice a definite deficit in that leadership. My performance with respect to my targets was also referenced, though I was told that the partnership wasn’t nearly as concerned about that at this time: “everyone is entitled to an off-year.”

My initial response to this feedback was absolute panic. As feedback about this kind of stuff goes, this was all very mild. However, I’ve been around the block enough times to know that this is how it starts. Many of my colleagues and friends have experienced mental wellness issues. I know that it starts with mild feedback but quickly escalates to more overt displays of displeasure over your “attitude” until you’re eventually fired because your employer thinks that you don’t really want to be there anyway. When I received my more mild feedback I really heard: “there’s something wrong with you. We don’t like you anymore. You’d better fix it.” In fairness, no one was saying that: it’s just what I heard.

I received that feedback about 5 months ago. This month, our associate evaluations were due. Every year associates have to fill out a reflective evaluation in advance of our employee reviews with management. The evaluations include the standard information you’d expect to see: “What are your goals for the upcoming year?;” “how can you achieve those goals?;” etc.

My evaluations have been relatively easy to fill out in the past. This year, in light of my performance and the feedback I received throughout the year, my evaluation was much more challenging. I decided I had two options: I could gloss over my weaker performance with a commitment to improving; or I could directly address the challenges I’ve grappled with.

Glossing over my weaker performance had some appeal. My numbers weren’t abyssal. Really, the only reason it’s noticeable is because I’ve had such positive success in every other year. Surely experiencing some shrinkage during one of the biggest recessions in a lifetime is forgivable or even expected. However, glossing over my performance didn’t address the feedback issue. Additionally, it potentially set me up for an impossible 2017. Promising to return to growth in 2017 might only lead to a more challenging review in 2018 if I can’t deliver.

On my personal evaluation, I decided to more directly engage with my employer about my personal challenges. I referenced the feedback I received. I was honest about my immediate internal response to the feedback, but then I praised the partnership for paying such close attention to the wellbeing of the associates and thanked them for their concern. I didn’t provide many details, but I hinted at the personal issues I’ve struggled with while referencing the major items (it’s no secret, at the firm, that my mother was diagnosed with cancer). I identified my hopes for 2017 but assured the partnership that I knew my challenges didn’t just evaporate with the change of the year (and, thus, reminding the partnership that my challenges didn’t just evaporate with the change of the year). And then, I expressly invited anyone on the management team or the partnership to talk to me about anything they wanted to talk to me about.

Inviting the partnership to talk to me was probably most challenging. However, I think it was the most important part of my evaluation. I needed the partnership to know that they could, and should, be open and transparent with me about any concerns they have. The partnership was clearly already having conversations about me. Inviting them to talk to me directly essentially gave me a place in that conversation. Also, getting more transparent and direct feedback allows me to try to be more responsive to specific concerns while being open about my own particular needs. Finally, opening up a dialogue with my employer helps with my own anxiety. Instead of panicking about the extent to which my employer is secretly hating me, I hope to have more confidence that I am, in fact, hearing everyone’s true concerns and that those concerns aren’t as catastrophic as my brain tells me they are.

Helpfully, Bell’s Let’s Talk day opened up a tiny crack in the door for me to make my invitation. My evaluation introduced Let’s Talk Day. I said that Let’s Talk Day helped me find the right way to address my challenges at work. I suggested that it’s a perfect opportunity for us to maintain openness in the partner/associate relationship. After introducing Let’s Talk Day I said:

“…It is important to me to be reliable and to meet your expectations, notwithstanding whatever else is going on for me. Please continue to discuss your concerns with me openly. I welcome your compassion but I also want to be valuable. I am open to receiving feedback and criticism about my work. Talk to me about your concerns; talk to me about my performance; talk to me about my work: let’s talk!”

This approach is not without its risks and I’ve yet to actually find out whether my experiment was successful (my review will take place next month). Certainly, I expect my frankness and vulnerability will catch the partnership off-guard. But I’m hoping that demonstrating my vulnerability and inviting my employer to be open with me about their needs will create a dialogue that will help both me and my employer to continue to develop a positive and mutually beneficial relationship. I’m experiencing a great deal of anxiety over my evaluation and my imagination is cooking up all sorts of nasty ways this could go horribly sour. But I know that another year of quiet suffering as my career erodes before my eyes would be the end of me. My vulnerability gamble might not work, but I’m thankful I’ve tried. I’m privileged and lucky enough to work in a place where an approach like this might have a shot. I figured I had to take a chance.

Win or lose, I’m glad Let’s Talk Day helped me find the framework to take this chance. Notwithstanding my current anxiety over my evaluation, I feel the most positive I’ve felt in a long time about the way my mental illness has impacted my career. I expect things will still be very hard and I might end up facing more dramatic loses to my career. But, for a moment, my mental wellness was no longer my own private burden to bear in the workplace.

B was able to use the Let’s Talk campaign as a way to start a conversation that he hopes his management will be open to. He’s in a good position because of years of steady growth, and because of his reputation within the firm.

Although I am hopeful and happy that B was able to take this step, I think that his story should be an indicator of how much more work still lies ahead. He is the outlier, in that he was able to leverage Let’s Talk day as an opening with his employer (though he isn’t sure yet whether this will be effective). He’s also in a better position to open up this conversation because his mental health challenges can be framed as situational, and externalized. The same is not true for individuals who are bi-polar, as Emily is, or who have other neurodivergences that can’t be situated so easily outside their core identity. In order for every person struggling with unsupported neurodivergences or mental illnesses to find help, acceptance, and equality, these conversations must move beyond the individualistic peer-to-peer model that is most common on Let’s Talk day (and beyond).

Similar to Flora’s concern that using her own name would negatively impact her employability in the future, B expressed concern about what he has witnessed when other individuals either admit to or are assumed to have mental health challenges. It is tragically common for unsupported neurodivergence to negatively impact employment. It happens too often, too easily, and is too quickly dismissed as a problem with the individual, for the individual to manage on their own.

In order for us to see significant, systemic changes that address both the issues that lead to so many people suffering with unsupported neurodivergences – unemployed, underemployed, homeless, and hungry – and that open up new and more holistic avenues to health, we need to push these conversations far past our current societal comfort zone. We need to start talking about the harms of systemic oppression on racialized, disabled, fat, poor, queer, trans, neurodivergent and otherwise marginalized folks.

We need to talk about intergenerational trauma, and about the deep harms of capitalism, colonialism, and systemic inequality. (These harms that hurt everyone, though not everyone equally. Inequality causes greater unhappiness in the poor as well as the rich. And our inability to speak openly about the ongoing harms of colonialism – not just on the colonized, though those harms are exponentially greater – but also on those of us descended from colonizers, who lack a connection to our own cultures and often feel that loss deeply but without any language to articulate and heal. The negative impact of these ongoing injustices is felt, to wildly varying degrees, by each of us. Healing these fractures in our social foundation will help everyone find easier and more accessible avenues to health.)

We need these awkward, uncomfortable, painful conversations.

We need them on Let’s Talk day, and we need them on every other day.

And we can’t do it alone. We can’t do it individually, in isolation and steeped in the shame that currently surrounds needing and accessing help.

Let’s Talk about where to find help

Valerie, a mental health clinician in Calgary, shared these resources for Calgarians:

– Distress Centre at 403-266-4357 (24 hour phones, plus walk-in therapy and crisis therapy)

– AHS Mobile Response Team – reached through Distress Centre, can see you at home or in the community

If you need to be seen in person more urgently, we recommend one of the Urgent Care sites:

Sheldon Chumir Urgent Care Mental Health

1st Floor – 1213-4th Street SW

Provides mental health assessments

Hours: Monday-Friday 08:00 am until 10:00 pm; weekends and statutory holidays 08:00 am until 08:00 pm

Phone: 403-955-6200

South Calgary Health Centre Mental Health Urgent Care

1st Floor – 31 Sunpark Plaza SE

Provides mental health assessments

Hours: 08:00 am until 10:00 pm; 7 days per week

Phone: 403-943-9383

If you’re interested in same-day, free, walk-in counselling, consider:

Eastside Family Centre

Suite 255, 495-36th Street NE

Provides counselling

Hours: Monday-Thursday 11:00 am until 07:00 pm

Friday 11:00 am until 06:00 pm

Saturday 11:00 am until 02:00 pm

Phone: 403-299-9696

South Calgary Health Centre – Single Session Walk-In

31 Sunpark Plaza SE (2nd Floor)

Provides counselling

Hours: M-Th 4:00 pm – 7:00 pm; Friday 10:00am to 1:00pm

Distress Centre – Walk-In

300, 1010 8th Avenue SW

Hours: Monday to Friday, 1:00pm to 4:00pm

403-266-4357

In emergency situations, please head to the nearest hospital emergency department.

If you want to discuss resources for yourself, or a loved one, consider calling Access Mental Health (403-943-1500, M-F 8-5) or 2-1-1 (24hrs).

The Greatist shared these 81 Awesome Mental Health Resources When You Can’t Afford a Therapist.

Healthy Minds Canada has compiled this comprehensive list of resources.

And, as of 2018, I also offer narrative therapy services. You can contact me at sostarselfcare@gmail.com.

Good luck, my friends. Let’s keep talking.

Part One: Mental health and corporate culture; Funding for mental health supports; Starting the conversation

Part Two: Hospitalization, and the “Scary Brain Stuff” – an interview with Emily; Long-term and alternative supports; The intersection of race and mental health

Part Three: Social determinants of health, and moving beyond individualism – an interview with Flora; Corporations

Part Four: Pushing the conversation out of the comfort zone – an interview with B.; Where to find help

Recent Comments